Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

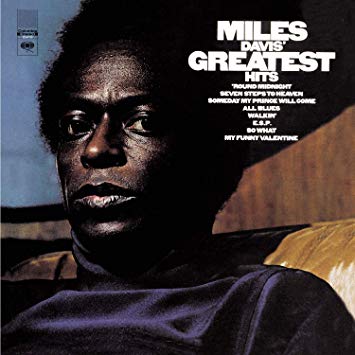

I must have read something, possibly a review in High Fidelity or Stereo Review, that piqued my interest in Miles. Having done so, the logical next step would have been to hop on my bicycle, pedal downtown to Collins Piano Company, and buy one of his albums. Unfortunately, Miles Davis’ Greatest Hits, an erratically programmed 1969 compilation of small-group sides recorded for Columbia between 1956 and 1965, was the only one that the store had in stock. I would have done better to start with Miles Ahead or Kind of Blue. But Miles Davis’ Greatest Hits was what I brought home with me that fateful day, and it turned the trick far more than adequately.

I put on the first track, “Seven Steps to Heaven,” an up-tempo swinger whose title refers to the seven-note staccato riff that sets the tune in motion. WIthin a minute—less than that, really—my mouth was hanging open with astonishment, not just at Miles’ crisp, elliptical solo but at the lighter-than-air accompaniment of Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, and Tony Williams, who sounded nothing like the rhythm sections I’d heard on the jazz albums in our living-room record cabinet. Their music had a right-this-second immediacy, a quality I’d been looking for without knowing it.

I had no idea who any of these three men were, much less that they were generally thought to be the most creative rhythm section in modern jazz. Nor did I know that Miles Davis himself was a unique figure in his own right, the only jazz musician who had succeeded in remaining innovative and influential throughout the greater part of his career. For that matter, I didn’t even think the Miles Davis Quintet was necessarily better (whatever that might mean) than Louis Armstrong’s All Stars or the Dave Brubeck Quartet. Even then, I knew by instinct that there were many mansions in the house of jazz, that you could move from one to the other as often as you liked, and that this flexibility was part of what made jazz so special.

“Attempts at a definition of jazz have always failed, and this reveals something about its mixed origins and later stylistic diversity,” Max Harrison wrote a decade later in the key article about jazz in the New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. He was, and is, exactly right. Jazz is a music distinctive above all for its ability to assimilate other musics without compromising its own clear identity. This has always been part of what I love most about jazz…and yet I also knew that I longed desperately to play bass someday in a band that sounded just like that.

I never did, of course. If I had, the rest of my life might have turned out very differently.

(To be continued)

* * *

To read George Frazier’s original liner notes for Miles Davis’ Greatest Hits, go here.“Seven Steps to Heaven,” by Miles Davis and Victor Feldman, performed by the Miles Davis Quintet in 1963. The band also includes George Coleman on tenor saxophone, Herbie Hancock on piano, Ron Carter on bass, and Tony Williams on drums:

“My Funny Valentine,” by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, performed by the Miles Davis Quintet on stage in Milan on October 11, 1964. George Coleman is replaced by Wayne Shorter:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.

To read about album #11, go here.

To read about album #12, go here.