Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums each weekday in the rough order in which I first heard them.

My father was for many years a member in good standing of the Columbia Record Club, the first of the many direct-mail “clubs” from which countless Americans of his generation who didn’t live close to a well-stocked record store bought vast numbers of LPs and, later, eight-track tapes and videocassettes. All of these clubs offered an introductory promotional deal that allowed you to get a dozen or so albums for next to nothing so long as you agreed to subsequently buy a fixed number of albums at full price. George Avakian, the legendary record producer, played a key role in the management of the Columbia Record Club, which was founded in 1955, and so made sure that it offered a generous selection of jazz LPs by Columbia’s artists, most of whom Avakian had signed and many of whose albums he produced. Several of them made their way into my father’s record collection, including Ambassador Satch, the only Louis Armstrong album that he owned and the first one I ever heard.

I explained how Ambassador Satch came to be recorded in Pops: A Life of Louis Armstrong, my 2009 biography. Armstrong and His All Stars, the trumpeter’s combo, spent much of 1955 criss-crossing Europe. The rapturous reception they received there did not go unnoticed at home:A few weeks earlier, while the tour was still underway, the New York Timeshad run a front-page story called “United States Has Secret Sonic Weapon—Jazz” in which the house organ of the liberal establishment claimed that Armstrong’s European concert tours had made him the “most effective ambassador” for the American way of life and offered a pointed suggestion: “What many thoughtful Europeans cannot understand is why the United States Government, with all the money it spends for so-called propaganda to promote democracy, does not use more of it to subsidize the continental travels of jazz bands…With a small Government subsidy, [Armstrong] might play the smaller intermediate towns and his tour stretched to six months by train instead of six weeks by bus.” The story had bureaucratic fingerprints all over it: “Somewhere in the official files of one of Washington’s myriad agencies all this has been spelled out. Because nothing has been done about it, more than one observant American traveling the Continent has remarked: ‘We don’t know our own strength.’” Two weeks later the Times ran a follow-up piece announcing that the State Department had decided to sponsor foreign tours by American jazzmen, and on December 15 the White House earmarked $92,500 to send Dizzy Gillespie’s band to the Middle East for the first in a long series of government-sponsored jazz tours intended to demonstrate to Third World countries that American capitalism was better than Soviet Communism.

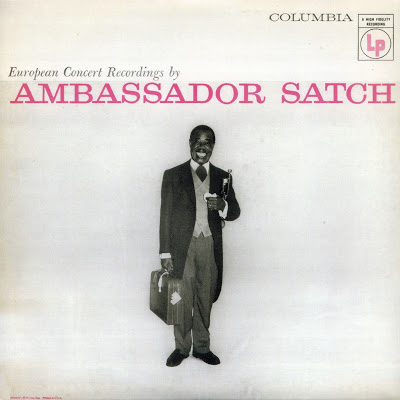

Avakian rushed to capitalize on the free publicity by taping an album by the All Stars to which he gave the ideal title of Ambassador Satch. The cover showed Armstrong dressed in a cutaway, holding a dispatch case in one hand and his trumpet in the other. The broad smile on his face, he told Ernie Anderson, was one of anticipatory pleasure: “It was the same morning I had already made a date with my connection to pick up half a pound of fine mutah. So when you see that picture of Ambassador Satch you know he’s got half a pound of fine jive right there in his satchel.”

Naturally, I didn’t know what was in Satchmo’s satchel when I first heard Ambassador Satch in 1969, nor did I know much of anything about him. I’d seen him singing “Hello, Dolly!” on What’s My Line! in 1964 and playing it on The Ed Sullivan Show later that year, but it wasn’t until I sat down with Ambassador Satch that I started to grasp that he wasn’t just a charming but old-fashioned minstrel-show entertainer with a wall-to-wall smile. While it isn’t the best record he ever made, it does feature one of the best bands he ever led, an explosively vital six-piece group featuring Edmond Hall on clarinet, Trummy Young on trombone, and Billy Kyle on piano, playing at the very top of its potent form. As for Armstrong, he was very much himself throughout Ambassador Satch, genial, expansive, and—whenever it suited him to be so, which was frequently—as hot as a cranked-up blowtorch.

To be sure, Ambassador Satch isn’t quite what it purports to be, a collection of concert performances recorded live in Europe. Several tracks were in fact taped in the studio and overdubbed with cheers and applause. Even so, it’s still enormous fun and, quite often, a great deal more than that. I can still remember how thrilled I was to hear Armstrong and his colleagues tearing into “Royal Garden Blues” and “Tin Roof Blues.” I wouldn’t be at all surprised to find out that they’d opened the satchel for a little taste before the tape started to roll.

I had no idea in 1969, of course, that I was destined to spend much of my middle age thinking and writing about Louis Armstrong. I expected to become either a concert violinist or a small-town schoolteacher. Little did I know that my destiny was hiding in the record cabinet tucked in the corner of the living room of my childhood home in Smalltown, U.S.A., waiting patiently for me to open the door.

(To be continued)

* * *

To read more about the making of Ambassador Satch, go here“Tin Roof Blues,” a track from Ambassador Satch, recorded live in Amsterdam in 1955:

Armstrong and the All Stars play “Muskrat Ramble” on Timex All-Star Show #2, originally telecast by CBS on April 30, 1958. The band also includes Hall, Young, and Kyle:

Louis Armstrong appears as the mystery guest on What’s My Line? This episode was originally telecast by CBS on March 22, 1964. John Charles Daly is the host and the panel includes Bennett Cerf, Arlene Francis, Ross Hunter, and Dorothy Kilgallen:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.

To read about album #6, go here.

To read about album #7, go here.

To read about album #8, go here.

To read about album #9, go here.

To read about album #10, go here.