Various forms of the records-that-changed-my-life meme have been making the rounds lately, so I came up with my own version, which I call “The Twenty-Five Record Albums That Changed My Life.” Throughout the coming month, I’ll write about one of these albums every weekday in the order in which I first heard them.

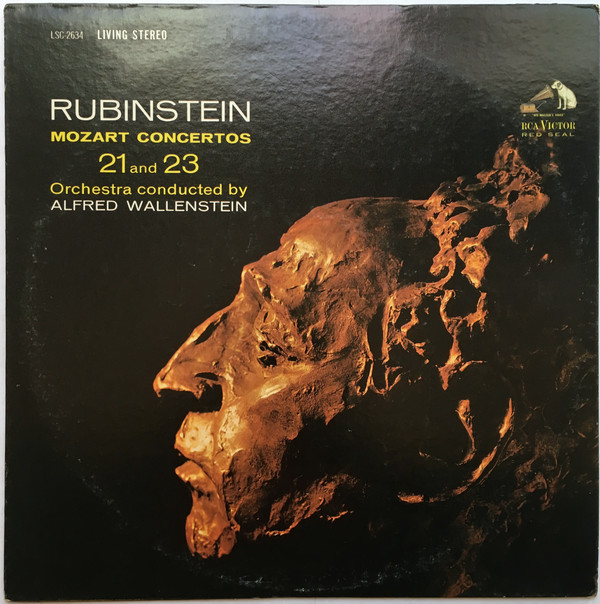

It scarcely seems possible, but I’ve been listening to this album, which introduced me to the music of Mozart, for fifty years. I bought it when I was thirteen, the same age as Arthur Rubinstein when he made his Berlin debut playing Mozart’s A Major Piano Concerto with an orchestra led by Joseph Joachim, his patron and Brahms’ intimate friend, in 1900. “He who can play Mozart so successfully is a chosen one among the elect,” one of the critics wrote, a sentence which the youngster got by heart and remembered for the rest of his long life.

Rubinstein adored Mozart’s music, but he rarely played it in public. Even so, he had a special affection for the divine simplicity of this particular piece, which he recorded three different times, in 1931, 1946, and 1962. This is the last of them, and while it is no longer my favorite recording—I’ve come to find his Mozart playing a bit on the pale side—I still love it, undoubtedly for sentimental reasons, which is just fine by me.

To discover Mozart is by definition a key moment in every musician’s life, he being the master of masters. So far as I know, the only artist of note who had a bad word to say about him was Noël Coward, who claimed that his operas sounded like “piddling on flannel.” Though it’s a funny line, my own feelings are more aptly summed up by Aaron Copland, himself a great composer, in a 1956 essay that I can do no better than quote in extenso:

It would be futile to try to single out any one work as my favorite, but the slow movement of this concerto is as good a pick as any. Each bar is suffused with a desperate, heart-tearing melancholy, yet Mozart never exaggerates his unappeasable sorrow: he is content merely to show it to you, in much the same way that Cézanne shows you the garden at Les Lauves, his country home, leaving the rest to your imagination.Paul Valéry once wrote: “The definition of beauty is easy: it is that which makes us despair.” On reading that phrase, I immediately thought of Mozart. Admittedly, despair is an unusual word to couple with the Viennese master’s music. And yet, isn’t it true that any incommensurable thing sets up within us a kind of despair? There is no way to seize the Mozart music. This is true even for a fellow-composer, any composer—who, bring a composer, rightfully feels a special sense of kinship, even a happy familiarity, with the hero of Salzburg. After all, we can pore over him, dissect him, marvel or carp at him. But in the end there remains something that will not be seized. That is why, each time a Mozart work begins—I am thinking of the finest examples now—we composers listen with a certain awe and wonder, not unmixed with despair. The wonder we share with everyone; the despaire comes from the realization that only this one man at this one moment in musical history could have created works that seem so effortless and so close to perfection.

(To be continued)

* * *

Maurizio Pollini plays Mozart’s A Major Piano Concerto, K. 488, accompanied by Karl Böhm and the Vienna Philharmonic. This performance was filmed in 1976:

Arthur Rubinstein plays the piano and talks about music in The Love of Life, an Oscar-winning 1969 documentary:

* * *

To read about album #1, go here.

To read about album #2, go here.

To read about album #3, go here.

To read about album #4, go here.

To read about album #5, go here.