Why did people back then seem to age so much more quickly than they do now? Part of the answer, of course, is that they died so much younger, and another part is that many of them led much harder lives than most of us do nowadays. The Great Depression left deep furrows on most of those who survived it (I’ve stood on bread lines/With the best,/Watched while the headlines/Did the rest). So did the world war that came in its wake. Is it any wonder that those who survived those twin cataclysms came away looking like they knew something about suffering?

I don’t think I do that, though I certainly enjoy the company of my younger friends and do my best to learn from them. I believe, too, in living in the moment. To be sure, I sometimes dream of the slower, nicer world I used to know and wake up missing it desperately, but then I look around me, shrug or laugh (depending on my mood), and go back to sleep.

Above all, I try never to act younger than I am. Very possibly as a result of this self-restraint, I’m told that I don’t look my age—at least not yet. I will, though, sooner or later, just as I will sooner or later start to feel it. Fortunately for me, the latter day seems nowhere near, not least because I’ve spent the past decade flinging myself into one fresh venture after another, than which there is no better way to stay young. The Letter, my first stage work and operatic collaboration, opened in Santa Fe ten years ago, followed a few months later by the first draft of Satchmo at the Waldorf. Since then I’ve written a second play and two more opera libretti, and I’ve also staged Satchmo twice. On top of all this, I continue to hold down a demanding job as the drama critic and arts columnist of a big-city newspaper, which would be more than enough in and of itself to keep most sixty-three-year-olds busier than they care to be. I wouldn’t have it any other way. As George Balanchine once said to a reporter, “I’m not going to retire, my dear—I’m going to die.”

Maybe so—and maybe not. My friend Heidi wasn’t planning to die at forty-nine, after all, any more than Balanchine foresaw being struck down by the wasting disease that reduced him to a pitiful shadow of himself before finally claiming his life. Dmitri Shostakovich doubtless had such ironies in mind when, toward the end of his own troubled life, he wrote the darkest piece of music I know, his Fourteenth Symphony, an orchestral song cycle whose subject is death. How did he feel about death, and what did he think his symphony “said” about it? Having learned from savagely hard experience to sculpt his public utterances to suit the requirements of the killers who ruled his native land, Shostakovich issued the following quasi-official statement about the Fourteenth Symphony:

I want listeners to reflect upon my new symphony…to realize that they must lead pure and fruitful lives for the glory of their Motherland, their people and the most progressive ideas motivating our socialist society. That is what I was thinking about as I wrote my new work. I want my listeners, as they leave the hall after hearing my symphony, to think that life is truly beautiful.

Maybe. But a man who had lived most of his adult life in the shadow of the KGB could surely never have meant that to be the sole and only point of the Fourteenth Symphony, a piece of music that reeks of the harshest possible pessimism. Far wiser to trust the tale, not the teller, and there can be no doubt of what tale is being told by the symphony’s final movement, a setting of a terse little poem by Rainer Maria Rilke called “Schlußstück,” which can be variously translated as “Conclusion” or (if you’re musically inclined) “Coda”:

Death is great.

We are his

when our mouths are filled with laughter.

When we think we are in the midst of life,

he dares to weep

in our midst.

It ends with a shocking gesture, a gratingly dissonant chord that is played forty times in a row, louder and louder, faster and faster, until the music stops dead (so to speak) in its tracks.

And is that all? Again…maybe. If there’s more, though, it is only through religious faith that we can imagine what such a “more” might be. For my part, I prefer, at least for now, to think not about what might be, but what is.

I place in evidence the closing lines of The Waverly Gallery, Kenneth Lonergan’s great play about the devastating effects of dementia on a close-knit family. They are words to live by:

It’s not true that if you try hard enough you’ll prevail in the end. Because so many people try so hard, and they don’t prevail. But they keep trying. They keep struggling. And they love each other so much; it makes you think it must be worth a lot to be alive.

It was to Heidi. It is to me.

* * *

Ella Carver appears on What’s My Line? This episode was originally telecast live by CBS on June 12, 1955:

The Who, introduced by Tommy Smothers, perform “My Generation” on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967:

“Schlußstück,” the finale of Shostakovich’s Fourteenth Symphony, performed in 1973 by Galina Vishnevskaya, Mark Reshetsin, Mstislav Rostropovich, and members of the Moscow Philharmonic:

* * *

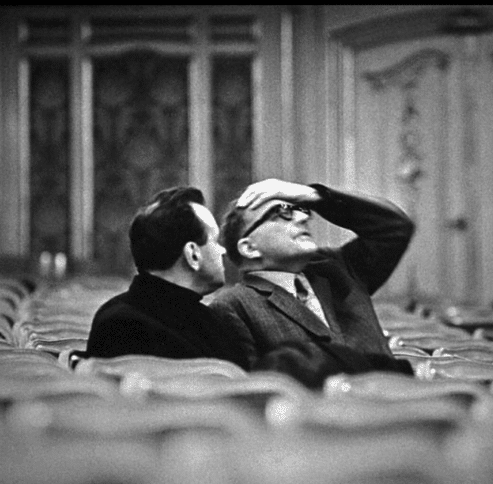

UPDATE: A Twitter follower who read this posting sent me the following photograph, for which I am most grateful: