I leaped out of bed and ran down the hall, and Mrs. T put the call on her speakerphone as soon as I got there. The coordinator told us to report to the hospital, which is a mile and a half south of our apartment, at nine-thirty sharp. Once we shook off our early-morning fog and realized that this was the real thing, we were full of questions, none of them complicated, for which the coordinator had similarly straightforward answers, most of which amounted to Here’s where you go and what you do when you get there. She reminded us that we’d be sitting around for several hours before Mrs. T was rolled into the operating room and should bring along a good book, then gave us an even better piece of advice: “If I were you, I’d go back to bed and get some sleep. You’ll be needing it.”

Mrs. T thanked her and hung up. We looked at each other. Then I said, “O.K., I’m going back to bed,” after which we both started laughing giddily.

It didn’t occur to either of us, not for a second, that the call might turn out to be a false alarm—or, as the doctors at New York-Presbyterian prefer to say, a “dry run.” Yet that was what it proved to be: the transplant coordinator called back a few hours later to let Mrs. T know that the donor lungs had proved unsuitable for transplant. Instead of going under the knife, she spent the following day in a long, exhausting string of previously scheduled appointments with various doctors at New York-Presbyterian, all of whom were as disappointed as we were. We returned home feeling…well, let down.

Dry runs are an aspect of organ transplant about which civilians, so to speak, know nothing. Yet they’re common enough, even routine. The reason why they happen is that transplant patients get the Big Call as soon as their doctors receive an organ offer. Unlike Mrs. T, most recipients don’t live twenty-two blocks from a transplant center, or even twenty-two miles. They typically need a fair amount of time to make it from their homes to the hospital, along with a built-in margin for error just in case the car won’t start. {New York-Presbyterian officially gives you three hours to get there, plus a little wiggle room.) Nor can they dally on the way: organs start to deteriorate as soon as they’re harvested. That’s why you’re called before the transplant doctors have actually seen the donor organ that you’re being offered, at which point they sometimes discover that it’s not in good enough shape to be used. This was what happened to us.

By coincidence, we had an appointment the next day with the thoracic surgeon who would have been cracking Mrs. T’s chest that evening had her donor lungs panned out. He told us that one of his other patients had survived nine dry runs before being successfully transplanted. We did our best to grin.

Mrs. T and I had known going in, of course, that we’d likely weather at least one dry run, if not more, before ringing the cherries. New York-Presbyterian requires its transplant candidates to attend a continuing series of seminars about the realities of transplant, some of which are extremely, at times even alarmingly frank. The lecture about the side effects of post-transplant drugs, which we’ve now heard at least three times apiece, has been known to induce nightmares in the easily susceptible. (I especially like the bit about how prednisone, an immunosuppressive steroid of which all transplant recipients must take large doses, can not only cause psychotic reactions but has also been known on occasion to make you grow hair in your ears.) Among many other things, we’d been warned at numerous seminars to expect dry runs. But this was our first Big Call, and we were too full of starting-bell beans to keep in mind that the odds that apply to every other transplant candidate apply to Mrs. T as well.

Ten days later, the same thing happened all over again, except that the phone rang not in the middle of the night but at eight p.m. We got the sorry-guys-better-luck-next-time message fifteen hours later, just as I was preparing to call a car service to drive us to the hospital. In every other way, it felt the same, though we didn’t get quite as excited the second time around. Still, we were no less sure that this summons, unlike its predecessor, would be the real right thing.

That was a week ago. Since then, the phone hasn’t rung.

So how’s Mrs. T doing? She has her good and bad days. The bad ones, as is to be expected with the end-stage pulmonary hypertension from which she suffers and the powerful meds that she takes, are slowly getting worse: more pain, more nausea, less stamina. She’s no longer able to leave our apartment save to see her doctors in New York and Connecticut. And while nobody has to remind us that patients are being transplanted at New York-Presbyterian, and lives saved, every day, we’re no less aware that New Yorkers don’t come close to pulling their weight when it comes to signing up to be organ donors.

Meanwhile, Mrs. T is hanging on, quite literally, for dear life. Nor has she given up hope. Yes, we’ve received two dry-run offers in a row, but the fact that they came in such close succession proves that she’s near the top of the recipient list, meaning that she has a good chance of receiving an offer that will result in surgery. The catch—to put it bluntly—is that she has to stay alive long enough to get transplanted. It’s sort of like when Peter Falk explains to Alan Arkin in The In-Laws that the CIA has a terrific pension plan. “The trick,” he adds, “is not to get killed. That’s really the key to the benefit program.”

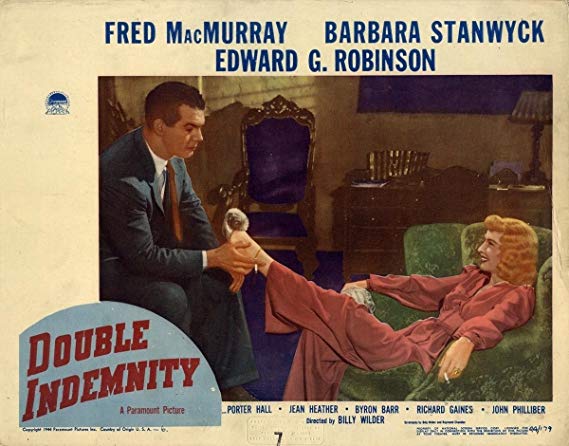

I have no doubt that Mrs. T will make it all the way to the finish line. She’s the toughest cookie in the jar. But optimism is like the mercury in a thermometer: it rises and falls. Or, to quote from another movie that I love, some days you win, some days you lose, and some days…it rains.

For the best possible description of how we’re feeling, though, I can’t do any better than to turn to Stephen Sondheim: I’ve run the gamut / A to Z. / Three cheers and dammit, / C’est la vie. / I got through all of last year, / And I’m here.

That she did—and that she will.

* * *

Elaine Stritch sings Stephen Sondheim’s “I’m Still Here” (from Follies) at Sondheim’s 2010 eightieth-birthday concert at Avery Fisher Hall, accompanied by Paul Gemignani and the New York Philharmonic:

* * *

One last thing: if you haven’t signed up to be an organ donor, please do it now. Desperately sick people from coast to coast—Mrs. T very much among them—are waiting for donor organs. Twenty of them will die today because no organs were available, and twenty more will die tomorrow.You could help save them. Won’t you?