“Scarcely anything material or established which I was brought up to believe was permanent and vital, has lasted. Everything I was sure or taught to be sure was impossible, has happened.”

Winston Churchill, My Early Life: A Roving Commission

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“Scarcely anything material or established which I was brought up to believe was permanent and vital, has lasted. Everything I was sure or taught to be sure was impossible, has happened.”

Winston Churchill, My Early Life: A Roving Commission

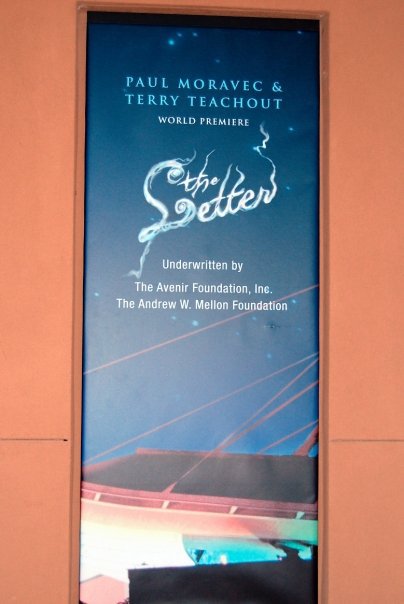

The Letter was Paul’s first opera, but he was already fairly well known as a composer by then (indeed, he’d won the Pulitzer Prize in 2004) and had dozens of major premieres under his belt. Not me. To be sure, I’d published several books, but they were biographies, a memoir, and a self-anthology, not works of imaginative literature. The fact that I’d now written the libretto for an opera by a Pulitzer laureate that was commissioned and premiered by one of America’s leading opera companies was…well, unusual.

The Los Angeles Times thought so, too, and asked me to write a piece about what I’d done and what it meant:As far as I’m concerned, critics aren’t artists. In my capacity as a critic and biographer, I think of myself as an artisan—a craftsman. One of the reasons why I believe this to be so is because I used to be an artist. I spent many years working as a professional musician, and that experience has conditioned my approach to criticism. I try to write not as a lofty figure from on high, smashing stone tablets over the heads of character actors and prima donnas, but as someone who has spent his whole adult life immersed in the world of art, both as a critic and, once upon a time, as a practitioner….

I’ve found in recent months that a good many theater professionals appear to be pleasantly surprised that I’m putting my money where my mouth is. Together with Paul Moravec and the other wonderfully gifted men and women with whom I am collaborating on the premiere of The Letter, I’m submitting myself for approval—not just from my fellow critics but from the people who read my reviews each week. On Saturday, they’ll find out whether I can walk the walk.

According to Simon Williams, who reviewed the premiere of The Letter for Opera News, I could: “The opera is an improvement on the play, which is verbose, faultily structured and moralistic; instead, Teachout’s terse libretto recaptures the stringent economy of the much finer story, also by Maugham, upon which the play is based.”

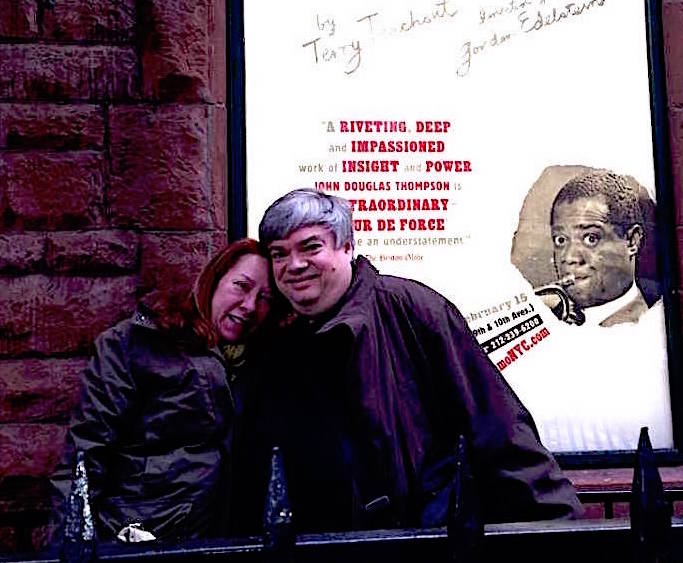

A few weeks after The Letter opened, Pops, my biography of Louis Armstrong, was published, an unplanned coincidence that kept me hopping for the remainder of 2009. I took it for granted—not without reason—that I’d never have another year as eventful as that one. Little did I know that within a few short months, I’d write the first draft of my first play, Satchmo at the Waldorf, that it would be subsequently be produced off Broadway and in seventeen other cities throughout America, and that I would be invited to direct two of those productions myself, in West Palm Beach and Houston.

Stranger things have happened, I suppose, but I know I had never imagined that I would someday write a play that other people might possibly want to produce, much less that it would be a commercial success. Nor did it occur to me at any point along the road to Satchmo that I might also become in due course a professional stage director—and do so at the improbable age of sixty. But writing The Letter had taught me how to write Satchmo, which gushed out of me in a three-day frenzy of near-nonstop work, and while I would spend the next couple of years revising that very rough draft, the essence of the thing was there right from the start.

The decade just past brought me joyful surprises beyond all imagining—but none so great as the entry into my life fourteen years ago of Mrs. T. Her love was the key that unlocked me, and turned me into a kind of writer that I had never dared to dream of becoming. I will spend all the rest of the days of my life overflowing with gratitude for that miraculous gift.

* * *

To read my account of the first performance of The Letter, written later that same night, go here.The first movement of Paul Moravec’s Violin Sonata, performed in 1993 by Maria Bachmann and Jon Klibonoff. This is the first piece by Paul that I ever heard, an experience that led directly to our friendship and subsequent collaboration:

“There is always a strong case for doing nothing, especially for doing nothing yourself.”

Winston Churchill, The World Crisis, 1911-1914

Andrés Segovia is interviewed by Jack Pfeiffer in an excerpt from an episode of Wisdom, originally filmed by NBC in 1961. He is heard at the beginning of the program playing Manuel de Falla’s Homenaje (Le Tombeau de Claude Debussy:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“At one point, he [Ravel] wound up a speech with the words: ‘Il faut toujours être de mauvaise foi en art [In art, you’ve got to be dishonest].’ Terrified and uncomprehending, I replied, with bated breath: ‘Oui, maître.’ Since then I have often thought of this statement, and it seems to me to be the whole explanation of art.”

David Ponsonby, unpublished manuscript (cited in Tony Scotland, Lennox and Freda)

The thirty-sixth episode of Three on the Aisle, the (usually) twice-monthly podcast in which Peter Marks, Elisabeth Vincentelli, and I talk about theater in America, is now available on line for listening or downloading.

Here’s an excerpt from American Theatre’s “official” summary of the proceedings:

To listen to or download this episode, read more about it, or subscribe to Three on the Aisle, go here.First, the critics are joined by Regina Castellanos, a recent graduate of the legendary performing arts summer camp Stagedoor Manor, to chat about her experiences there and what theatre means to her and her peers more generally. Then, they turn to fellow Stagedoor alumnus Larry Owens, who’s now starring in A Strange Loop at Playwrights Horizons. They discuss the classic musicals that first cemented his love of the genre, his own time at Stagedoor (including one particularly memorable summer performing alongside Beanie Feldstein), and how those experiences have informed his art ever since.

Finally, Peter, Terry, and Elisabeth reflect on the best and worst shows they’ve seen lately, including Halley Feiffer’s Moscow Moscow Moscow Moscow Moscow Moscow, George Brant’s Tender Age, and David Auburn’s production of The Skin of Our Teeth at the Berkshire Theatre Festival….

In case you’ve missed any previous episodes, you’ll find them all here.

From 2009:

Read the whole thing here.The Santa Fe Opera will perform The Letter six times, and it’s entirely possible that it will never be seen again after that. Even if it should be taken up by other companies, it won’t be done in the same way that it’s being done here and now. Is it any wonder, then, that I want to hurl myself into this unrepeatable, irreplaceable experience–that I want, as actors say, to be as “present” as I can possibly be?…

“The motivations of his characters are described with infinite subtlety, but they themselves are boring (one would surely run a mile rather than actually encounter the princess de Guermantes or M. de Charlus).”

Lennox Berkeley, diary entry, December 1, 1973

An ArtsJournal Blog