It was fun—it still is—but when Mrs. T’s health started to decline in the spring of 2017, I decided that it would be prudent to cut back on my theater-related air travel, and the string of crises that beset us during the second half of 2018 forced me to suspend it entirely and stick close to home. Once Mrs. T’s condition became more or less stable again, I took a deep breath and considered what to do next. I knew that I wanted to be where she was as we continued to wait for her double lung transplant. At the same time, it looked as though the two of us might be able to manage a limited amount of theater-related travel by car during the first part of the summer, so I drew up a tentative plan that would take us to various stops in the Hudson Valley and New England in June and July. In addition, though, she urged me to make a quick solo trip to Chicago and Smalltown, U.S.A., while it was still possible for us to be apart, knowing that I wouldn’t be able to leave her again for an unknowable amount of time after her surgery.After Florida, he’s flying to San Diego and San Francisco, then Kansas City, Chicago, and Lenox, Mass. In the middle of all that, he’s flying back to New York City to review the opening of Chekhov’s The Cherry Orchardat the Brooklyn Academy of Music, then the opening of Richard Greenberg’s play, The American Plan, which will premiere on Broadway.

Likewise the lazy Sunday afternoons on which David, Kathy, and I sit in the living room and watch Westerns on TV. We know them well, in some cases well enough to recite the dialogue along with Randolph Scott and John Wayne, but we watch them anyway. It’s just another way for us to be together, and we don’t have to say anything to one another to relish the uncomplicated, increasingly rare pleasure of being in the same room at the same time.

Certain acts of communion, however, are by their nature private. I drive through Smalltown on my own so that I can be alone with my memories, some of which are too sad to share. It pierced my heart, for instance, to see Matthews Elementary, the neighborhood school that I attended from 1962 to 1968, for it closed its doors at the end of the school year just past. It was at Matthews that I first learned how to play a musical instrument—the violin—and was told by Jackie Grant, my second-grade teacher, that President Kennedy had been assassinated. You can see Matthews from the front door of 713 Hickory Drive, the house where I grew up and where David and Kathy now live, but that won’t be true for much longer. It is, I gather, destined to be torn down soon, and when it goes, a piece of my soul will go with it.

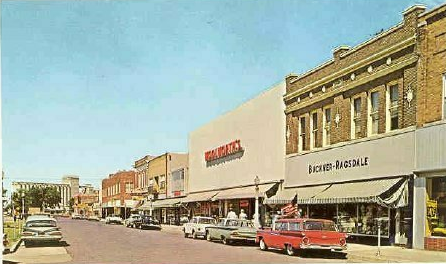

Smalltown has changed in countless other ways since I was a student at Matthews Elementary. To be sure, it continues to look very much like the home town of my youth: most of the buildings that I remember from my youth are still there, though many of them have long since been remodeled and “repurposed.” The biggest changes are harder to see unless you know where to look. I ate my biscuits and gravy at a table for one, reading Andrew Roberts’ Churchill: Walking With Destiny as I did so, and it startled me (albeit pleasantly so) when a cheerful young girl walked up to my table and said, “That’s a big book you’re reading! What’s it about?” What was even more surprising, at least to an ex-Smalltownian of a certain age, is that the girl was black. Not only would she never have spoken to me so unselfconsciously in 1962, but she probably wouldn’t have been there in the first place, since the Smalltown of my early childhood was segregated by race.

Another thing that’s changed is that nobody in Jay’s, or anywhere else, recognized me. Time was when most people in Smalltown knew who I was, at least well enough to say hello, but that time is long gone. Now I’m a walking ghost, a wraith from elsewhere who is as invisible to his fellow townsmen as Emily was to the citizens of Grover’s Corners when she came back to earth to relive her twelfth birthday. They see me, but they don’t know me, and if they should happen to say hello, they’ll be talking to a stranger. I kept wanting to cry out, “Mama, I’m here! I’m grown up! I love you all! Everything!”

I paid a different kind of homage to the past when, on the last night of my stay, David and Kathy drove us to Paducah, Kentucky, for a concert by America, whose founding members started playing together forty-nine years ago—their first hit single, “A Horse With No Name,” went to the top of the charts in 1972—and have been on the road ever since. I taught myself guitar by strumming along with some of America’s early records, but it’d been a quarter-century, if not more, since I’d last heard any of them, and I was amazed by how well I remembered all of the songs they played that night at the Luther F. Carson Four Rivers Center. It moved me, too, to see and hear how hard Dewey Bunnell and Gerry Beckley worked to give honest pleasure to an audience so firmly in the thrall of nostalgia that they would probably have been just as happy if the band had phoned it in and run for the bus.

I’ve no idea when I’ll return to Chicago, or to Smalltown. It will likely be quite some time before I see David, Kathy, or Laura again. So I’m glad to have a few new memories to store alongside what Louis Armstrong called “the good old good ones.” Be they old or new, you can never fill up your heart’s scrapbook with enough pictures of the people—and places—that you love.

* * *

Iris DeMent sings “Our Town,” written by her and accompanied by Emmylou Harris: