Helen Frankenthaler appears on Charlie Rose. This episode was originally telecast on April 12, 1993:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Helen Frankenthaler appears on Charlie Rose. This episode was originally telecast on April 12, 1993:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“People are rendered sociable by their inability to endure solitude, that is to say, their own society. They become sick of themselves. It is this vacuity of soul which drives them to intercourse with others.”

Arthur Schopenhauer, Counsels and Maxims (trans. T.B. Saunders)

“I never found the companion that was so companionable as solitude.”

Henry David Thoreau, Walden; or, Life in the Woods

The Thad Jones/Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra plays Jones’ “Central Park North” on Danish TV in 1969. The soloists are Jones on flugelhorn, Snooky Young on trumpet, Jerome Richardson on soprano saxophone, and Lewis on drums:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“It is a test (a positive test, I do not assert that it is always valid negatively), that genuine poetry can communicate before it is understood.”

T.S. Eliot, Dante

From 2009:

Read the whole thing here.Small children know nothing of the future: they barely know the difference between today and tomorrow. What they see is what there is. Do I know better now? I wonder. Samuel Beckett said it: “We have time to grow old. The air is full of our cries. But habit is a great deadener. At me too someone is looking, of me too someone is saying, He is sleeping, he knows nothing, let him sleep on.”

Have I awakened at last from my youthful dream of the eternal present, forty-seven years after my first class photo was taken, the one at which I now look with bemusement?…

“There is a luxury in self-reproach. When we blame ourselves, we feel that no one else has a right to blame us. It is the confession, not the priest, that gives us absolution.”

Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

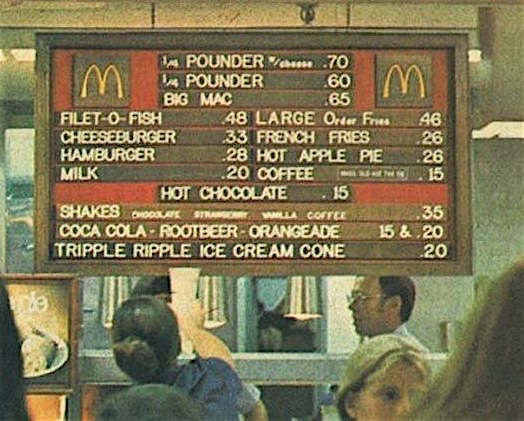

I stopped at a McDonald’s for a snack while driving from Connecticut to New York the other day. I ordered a two-cheeseburger meal, which is what I usually get at McDonald’s when not eating breakfast. I wouldn’t dream of trying to tell you, though, that the McDonald’s cheeseburger is anything special. In fact, it’s the most nondescript of sandwiches, designed for near-instant preparation and similarly quick consumption, consisting as it does of a paper-thin ground-beef patty, a limp slice of American cheese, a couple of dill pickle chips, a sprinkling of freeze-dried onion flakes, and a splash of ketchup, all squashed between the halves of a white-bread bun. It doesn’t hold a candle to the Quarter Pounder, which is superior in every way—yet I remain stubbornly loyal to the penny-plain cheeseburger.

Why is this so? The reason came to me from out of the blue midway through my second burger: it reminds me of my childhood.

When I was a boy, my mother made dinner six nights a week, and the four Teachouts sat down together at the kitchen table to eat it. That was part of what it meant to be a member of a happy family In the Sixties, which is what we mostly were. On the seventh day, though, she rested, and my father either took us all out to eat or grilled on the patio. Some weeks we went to “real” restaurants, where we ate steak, chicken, fish, or pizza in a dining room, and some weeks we went to a drive-in. For a long time we frequented the local A&W, but the first McDonald’s in the vicinity of Smalltown, U.S.A., opened in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, in the summer of 1968, and it quickly became one of our regular Saturday-night stops, no doubt in part because dinner for four chez McDonald’s was considerably cheaper than a sit-down restaurant. Not that my brother and I cared in the least: we liked it every bit as much, maybe even more.

In those far-off days of limited choice, McDonald’s sold just five sandwiches: hamburgers, cheeseburgers, the Big Mac, the Filet-o-Fish, and the Quarter Pounder, the latter available with or without cheese. I always ordered a cheeseburger, which I thought ambrosial, in part because I got to eat it sitting in the back seat of the car, which was almost as good as a picnic. I was still young enough to revel in such outings, and there was nothing I liked more than piling into the station wagon, riding up to Cape Girardeau, eating a cheeseburger, and coming home to Smalltown at dusk, singing “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” and “Oh! Susanna” with my family all the way to Cape and back. I doubt we ever felt much closer to one another than we did on those Saturday nights.

Boyhood, however, gave way in due course to adolescence and its roiling discontents, and while the four Teachouts continued to sit down to dinner each night, our weekly family outings grew increasingly awkward and uncomfortable. It was only a matter of time before I was making a point of being otherwise occupied on Saturday nights, and not long after that I went off to college, never again to live in the house where I grew up save as a visitor.

From then on and for many years to come, the McDonald’s cheeseburger ceased to figure prominently in my diet. Having moved to Kansas City and, later on, New York, I was too busy seeking out big-city cuisine to spend much time partaking of the fast food of my youth.

It wasn’t until some time later that I rediscovered McDonald’s, in part because of the introduction of its all-day breakfast, an innovation well suited to the culinary needs of those who spend a lot of time alone on the road. In the process I also rediscovered the humble McDonald’s cheeseburger, though it took longer for me to realize that it was triggering the same kinds of memories that the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea had once evoked for Marcel Proust:An exquisite pleasure had invaded my senses, something isolated, detached, with no suggestion of its origin. And at once the vicissitudes of life had become indifferent to me, its disasters innocuous, its brevity illusory—this new sensation having the effect, which love has, of filling me with a precious essence; or rather this essence was not in me, it was me. I had ceased now to feel mediocre, contingent, mortal. Whence could it have come to me, this all-powerful joy? I sensed that it was connected with the taste of the tea and the cake, but that it infinitely transcended those savours, could, no, indeed, be of the same nature. Whence did it come? What did it mean? How could I seize and apprehend it?

For me as well: eating a McDonald’s cheeseburger now fills me with memories of one of the most joyful parts of a largely happy life. And while it can be no substitute for the lost presence of my beloved parents, its commonplace flavor brings them to mind as clearly as if they were sitting across the kitchen table from me. Contingent and mortal I surely am, but as long as I live, they will, too.

* * *

“The Big Game,” a 1967 McDonald’s TV commercial:

Johnny Cash sings “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” in 1973:

An ArtsJournal Blog