I first learned that certain rich people had telephones in their cars from a short-lived TV series called Burke’s Law. Gene Barry, the star, played a wealthy Los Angeles homicide detective who was chauffeured to and from crime scenes in a Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud II that was equipped with a phone. I was seven years old when Burke’s Law made its debut on ABC in 1963, so the fact that Amos Burke had a phone in his Rolls must have made a huge impression on me, since I had no doubt thereafter that a car phone was the ne plus ultra of luxury.

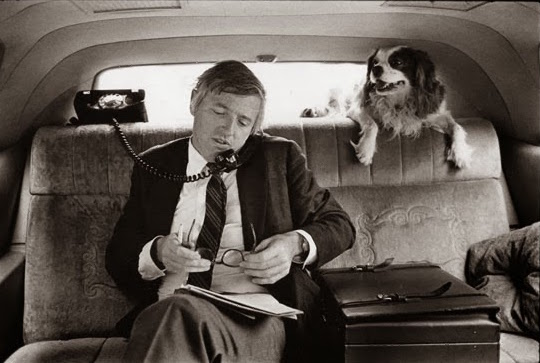

It wasn’t until I moved to New York in 1985 that I first got to know a person, William F. Buckley, Jr., who had a mobile phone in his stretch limo. Even then, I still found it to be fantastically ritzy. Had you told me in 1963—or 1985—that such phones would become obsolete long before I reached middle age, much less that I would live to see a fully mobile phone in every person’s pocket, be he rich or poor, I would have laughed in your face.

I’m sure I would have felt much the same way about the long-unimaginable prospect of owning a home videotape recorder. The Sony CV-2000, the first such device to be commercially marketed, cost $695 in 1965, the equivalent of $5,600 today, which put it far out of reach of people like my parents. Nevertheless, I bought my first VCR eighteen years later, and I soon took its life-changing existence for granted.

Most people see the present-day ubiquity of such devices as a chapter in the fast-moving history of technological change, which has transformed the daily life of the average American family almost beyond recognition. It’s easy to forget that as late as 1940, 45% of all Americans did not yet have “indoor plumbing,” meaning a flush toilet, a sink with a faucet, and a bathtub or shower. Today, by contrast, virtually all of us do. We can also eat all the caviar we want, the once-exorbitant price of that quintessential luxury good having been cut in half by the coming of cheap Chinese caviar that reportedly tastes just as good as the Russian kind.

In Chinatown, J.J. Gittes finds it impossible to understand why Noah Cross would be willing to do anything, up to and including murder, to corner the market on Los Angeles’ water supply. “Why are you doing it?” he asks Cross. “How much better can you eat? What can you buy that you can’t already afford?” To which Cross famously replies, “The future, Mr. Gittes—the future!” I’m not absolutely certain what he means when he says that, but I do know that whatever it is, Noah Cross’ future isn’t something I care to have. I’m content with the present—and the partner with whom I share it. Next to that pleasure, all others pale to the point of invisibility.

* * *

“Mobile Telephones,” a 1949 promotional short for the Bell System’s newly inaugurated Mobile Telephone System:

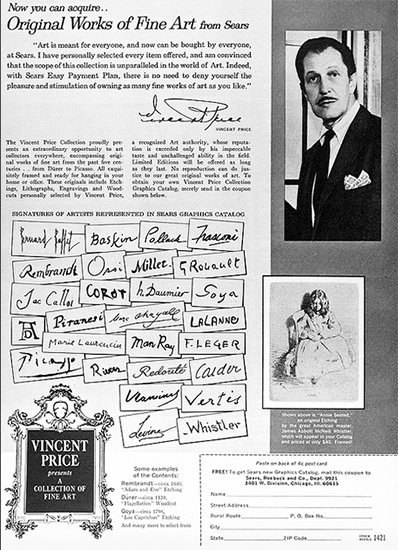

A 1962 training video made by Vincent Price for Sears in which he explained to the company’s salespeople how to market the Vincent Price Collection of Fine Art: