“It’s only those who do nothing that make no mistakes, I suppose.”

Joseph Conrad, An Outcast of the Islands

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“It’s only those who do nothing that make no mistakes, I suppose.”

Joseph Conrad, An Outcast of the Islands

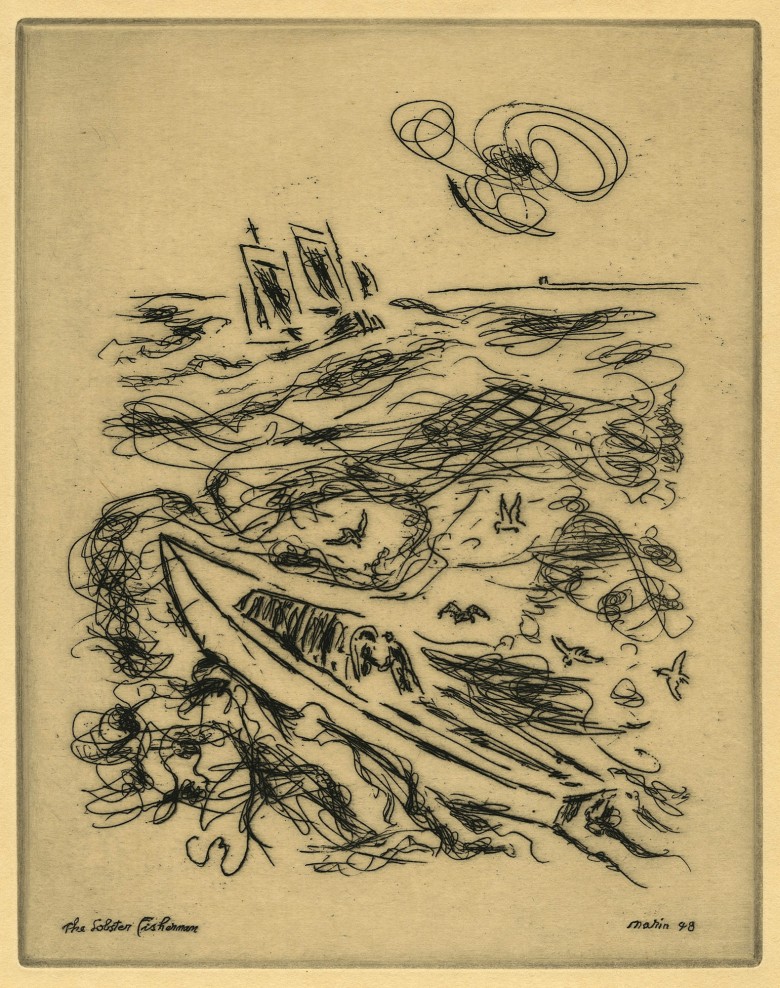

I have trouble keeping secrets from Mrs. T, something that amuses her no end, but I somehow managed to order “The Lobster Fisherman” and get it framed on the sly, and I’m delighted to report that it went over big when I finally brought it home to Connecticut last week.

Marin, America’s first cubist and one of the twentieth-century artists whose work means the most to me, is best remembered today for his watercolors. I use the term “remembered” somewhat loosely, for he is no longer very well known by name, either in this country or elsewhere. Such, however, was not always the case, as I explained when I wrote a column about Marin and his work that ran in The Wall Street Journal back in 2011:

Sooner or later, everyone who writes about John Marin gets around to mentioning the 1948 Look magazine poll of 68 critics, curators and museum directors who, when asked to name America’s greatest living painters, put him at the top of the list. Five years later, the headline of Mr. Marin’s New York Times obituary described him as “Artist Considered by Many as ‘America’s No. 1 Master.’” No less a highbrow than the art critic Clement Greenberg concurred, predicting that Mr. Marin and Jackson Pollock would “compete for recognition as the greatest American painter of the 20th century.”

So why does Mr. Marin so often get the “John Who?” treatment? For it’s better than even money that unless you happen to be a connoisseur of American modernism or an art-history major, his name is unknown to you. It’s been 21 years since a major U.S. museum last put together a full-scale retrospective of his work. New York’s Museum of Modern Art owns 25 Marins—but not a single one of them is currently on view….

Why, then, is Mr. Marin so underappreciated by the art-world elite? The standard explanation is that even though he marched to the edge of abstraction, it seems never to have occurred to him to turn his back on the visible world. “The sea that I paint may not be the sea,” he wrote, “but it is a sea—not an abstraction.” After the rise of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s, his deep-rooted belief in representation came to be seen as old-fashioned, even quaint.

Nothing, alas, has changed since then: Marin remains the most underappreciated of American masters. The good news, however, is that this makes him more affordable to those of us who know his worth. To be sure, Marin’s watercolors are well above my pay grade, but his best etchings are precisely comparable in quality, and the two that I love most, “Downtown. The El” and “The Lobster Fisherman,” happen to have been printed in larger-than-usual editions, thus making them accessible to collectors of modest means. In addition, these two etchings represent between them his favorite subjects: the first is an urban cityscape, the second a marine study. To own them both, then, is to own a Marin Museum in miniature.

Not surprisingly, “Downtown. The El” was one of the very first pieces of art that I bought, a couple of years before I met Mrs. T. I wrote about the purchase in 2003, on the day that this blog first went live:I just bought a copy of John Marin’s 1921 etching “Downtown. The El,” and it’s a beauty—a nervous cubist spiderweb that captures some of the sheer excitement of this crazy city in which I insist on living. It’s already taught me a lesson, which is that the ultimate test of the quality of a work of art is whether you can look at it every day without getting bored or irritated. So far, so good.

“Downtown. The El” now hangs over the couch in our Manhattan living room, and I look at it as often and as appreciatively today as I did sixteen years ago. For some reason, though, it never occurred to me to buy a copy of “The Lobster Fisherman” until I realized that it would make an ideal present for Mrs. T, a bred-in-the-bone New England girl who loves lobster and everything to do with its catching and cooking as much as she does modern art.

I started searching, and within a couple of weeks I’d found a flawless, richly inked impression of “The Lobster Fisherman,” one whose only “defect” made it an even more attractive purchase. Marin, it seems, never got around to pencil-signing this particular copy, an oversight that erased a zero from the end of the price tag—and yes, we’re talking three figures, in case you’re wondering whether you can afford to buy real art. Believe me, you can. (I knocked down the exquisite 1888 Berthe Morisot etching in the hall of our Manhattan apartment for a hundred dollars.). Now Mrs. T is happily fussing over where to hang it.

For those of you interested in such things, “The Lobster Fisherman,” which was etched in 1948 and printed two years later in an edition of 125, is based on a much lesser-known oil canvas of the same name that Marin also painted in 1948. (Its present whereabouts are unknown, at least to me.)

As is not infrequently the case with prints that have been based on pre-existing paintings, the etching reduces the painting to a simpler, even more immediately arresting image, an electric tangle of scrawled lines of black ink that puts me in mind of what an anonymous staffer for Life wrote about Marin’s work in 1950:

His scenes of the Maine coast, sailing ships and towering city skylines are never entirely realistic yet never unrecognizably abstract. They are glimpses into a single moment—the jostling of a city mob or the whipping of the wind through a schooner’s rigging.

Mrs. T and I lost our hearts to the coast of Maine the first time we went there, but until now we had yet to acquire a piece of art that reminded us of how we feel about it. (This one, for instance, always makes us think of our many visits to New York’s Hudson Valley.) Whenever we look at “The Lobster Fisherman,” I expect it will fill us both with memories of some of the best times we’ve spent together. This, too, is one of the special joys of living with art.

For the record, copies of “The Lobster Fisherman” are also owned by the Georgia Museum of Art, Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts, New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, Washington’s National Gallery of Art, Phillips Collection, and Smithsonian American Art Museum, and in the John Marin Collection of Maine’s Colby College Museum of Art. I have yet to see it hanging in any of those fine institutions, though, and I doubt they care about their copies as much as the curator of the Connecticut branch of the Teachout Museum will henceforth care about hers.

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“I often tell myself now—Stravinsky has no other notes, or no more notes to work with, than I have, or anybody else. We all have to choose between the same ones. So the important thing is the exercise of choice.”

Lennox Berkeley, letter to Nadia Boulanger, October 26, 1949

* * *

Not so long ago, Glenda Jackson’s “King Lear” would have come as a surprise. Now it feels like an inevitability. Gender-blind Shakespeare productions border of late on the commonplace—I first saw one, Oregon Shakespeare’s “Julius Caesar,” back in 2011—and Ms. Jackson had already played the title role of “King Lear” two years ago in a different production at London’s Old Vic. The real surprise about this “Lear,” directed by Sam Gold, is that it is running on Broadway, where Shakespeare’s darkest, most disturbing tragedy has been produced only twice in the past six decades, in 1968 with Lee J. Cobb and in 2004 with Christopher Plummer. Today, though, “Lear” is well on the way to becoming one of Shakespeare’s most popular plays, so much so that this is actually the sixteenth “Lear” I’ve reviewed in this space (Mr. Plummer’s was the first).

The big question, then, is not “Is Ms. Jackson’s ‘Lear” news?” but “Is it good?” The answer, in a word, is…mostly. It’s a mixed bag, but the best parts, of which there are many, will sear themselves into your memory like mental pictures of an unimaginable disaster—which is, after all, what “King Lear” is—while the unsatisfying aspects of Mr. Gold’s staging are never less than tolerable.

If you had the good luck to see Ms. Jackson in last season’s Broadway revival of Edward Albee’s “Three Tall Women,” in which she played a rich, senile matriarch, then you won’t be altogether surprised by her approach to “King Lear.” As has been the case with many previous Lears, it takes her a while to get up to speed. Ms. Jackson’s harsh baritone voice has no top, which flattens out the poetry of the first part of the play, and her physical slightness—she is the shortest person in the cast and looks rather like an androgynous marionette—puts her at something of a visual disadvantage. Yet there is nothing slight about her imperious manner, and once the storm blows away her illusions and she declines into self-protective madness, she comes decisively into her own….

Ms. Jackson is not, however, the only member of the cast who is giving a performance on the highest possible level. Indeed, Jayne Houdyshell is so remarkable as the Earl of Gloucester that there are moments when it’s tempting to call her the star of the show. Ms. Houdyshell is a great actor who is usually cast in smallish, quirky parts—this is the first classical role in which I’ve ever seen her—and it is thrilling to watch her expand to fill the space occupied by Gloucester, speaking Shakespeare’s verse with a luminous clarity of which I’d never suspected her to be capable….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.* * *

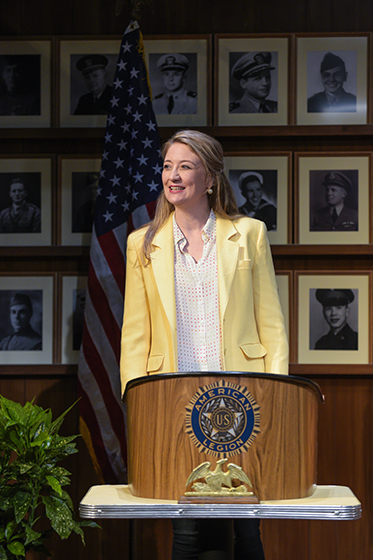

Rarely has a new play by a modestly well-known writer been greeted with such lockstep enthusiasm as has Heidi Schreck’s “What the Constitution Means to Me.” The off-Broadway run having received universally favorable reviews, Ms. Schreck’s play has transferred to Broadway, where it is being touted as a Tony-and-Pulitzer favorite. Sometimes such unanimity is a sign of distinction, but just as often it’s an indication that a play is going over big because it tells the audience precisely what it wants to hear—and nothing more. Such is the case with “What the Constitution Means to Me,” which is not without merit but is no more a masterpiece than Tarell Alvin McCraney’s “Choir Boy,” another recent hit that clangs the bell of cozy progressive sentiment.

If you’ve seen any of Sarah Ruhl’s plays, you’ll recognize the tone and approach of “What the Constitution Means to Me,” which is very much in Ms. Ruhl’s aggressively ingratiating manner. It’s a three-person show in which Ms. Schreck plays herself in the present and at the age of 15, back in the days when she earned scholarship money by entering public-speaking tournaments. Her specialty was the American Legion-sponsored competition that gives her play its title. The scene is a small-town American Legion hall circa 1989, and the first part of the play consists of what Ms. Schreck claims to be a close replica of her prize-winning speech, interspersed with present-day reminiscences of her youth, family life and ancestors….

I mentioned a moment ago the tone of Ms. Schreck’s play and performance. It is the most Ruhl-like aspect of “What the Constitution Means to Me,” for the 15-year-old self whom she portrays in the show is, not to put too fine a point on it, effusively twee: “When I was a little girl, I had an imaginary friend named Reba McEntire. She was not related to the singer. Just because the Constitution does not proclaim the having of imaginary friends as a right does not mean I can be thrown in jail for being friends with Reba McEntire.” The point, I assume, is to show us what Ms. Schreck was like prior to her emergence as a mature, wised-up feminist who has put away childish things, though it turns out that her grown-up self is also given to Ruhl-style explosions of coyness…

These, however, have a different purpose, which is to make the serious section of her play more palatable. That part is in fact devastatingly harsh, for most of Ms. Schreck’s male ancestors, her father excluded, were vicious brutes who treated their spouses and children so savagely that the audience at the preview I attended gasped—as well it should have—to hear what they did. No amount of sugar can make such a spiky pill go down more smoothly, and Ms. Schreck’s account of her heritage of violence is by far the best part of “What the Constitution Means to Me.” The problem, one that is again familiar from Ms. Ruhl’s work, is that Ms. Schreck, for whatever reason, is rarely willing to grapple directly, at least not for very long, with the raw emotions triggered by her truth-telling. Hence she slathers them with a thick layer of Irony Lite…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.Heidi Schreck talks about What the Constitution Means to Me:

Glen Campbell and the Smothers Brothers sing “Thank You Very Much” on The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. This episode was originally telecast by CBS in February of 1968:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“His liking for Chinese art was an affair of the mind; in a world of increasing noise and hugeness, he turned in private to gentle, precise, and miniature things.”

James Hilton, Lost Horizon

An ArtsJournal Blog