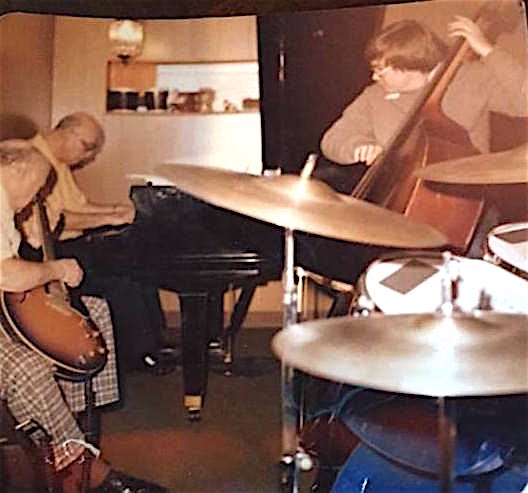

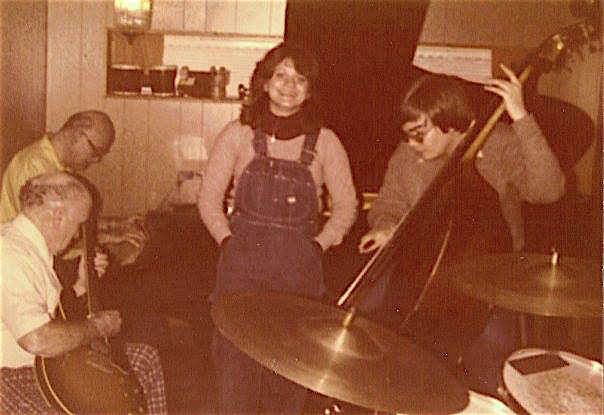

I thought of Harry when a friend of mine posted a snapshot of him on Facebook the other day. Taken at a party in his studio, it showed Harry at the piano, his friend and musical partner Epp Roller on guitar, and me on upright bass, jamming on some unknown tune. The party had taken place a few months before Harry’s sudden, unexpected death. It’s strange to think that I’m two years older than he was then. Like so many men who grew up in the Great Depression, he’d prematurely acquired the settled habits of old age, dressing and talking as though he were in his seventies.

Harry has been on my mind ever since I first saw that snapshot, but I said what I had to say about him in City Limits, so instead of going over well-tilled ground, I’ve decided to reprint a shortened version of “My Friend Harry,” the chapter in which I wrote about our friendship. I hope you like it, and that it gives you some sense of how much he meant to me.

* * *

I was twenty-two when I met Harry Jenks, the first great jazz musician to enter my life. He taught me more than any of my teachers, and meant as much to me as a person as anyone outside my immediate family. Not a week has gone by since his death that I haven’t thought about him.

I owe our acquaintance to the stubbornness of my friend Pam Jackson, who was then a piano major at William Jewell College, my alma mater. Pam had been introduced to Harry by her best friend, a fellow piano major named Dee Dee Hunter who had studied with him when she was growing up in Independence, Missouri, the quiet suburb of Kansas City that was home to another Harry, Harry S. Truman. Harry, Pam told me, had been a fixture on the Kansas City jazz scene until his eyesight started to fail, after which he lapsed by slow degrees into semiretirement. Now he made his living by teaching piano to the boys and girls of Independence and giving concerts at retirement homes with a banjo player named Epp Roller. In addition, Harry and Epp held down a regular Saturday-night gig at a Shakey’s Pizza Parlor in Independence, where they played for anyone who cared to listen. (Shakey’s was a chain of pizza restaurants that once upon a time hired old-fashioned banjo-powered jazz combos as a matter of policy.) Since both men were as bald as cueballs, they called themselves “The Skinheads.” Epp was good, Pam said, but Harry was the one I had to hear, because he sounded just like Art Tatum.

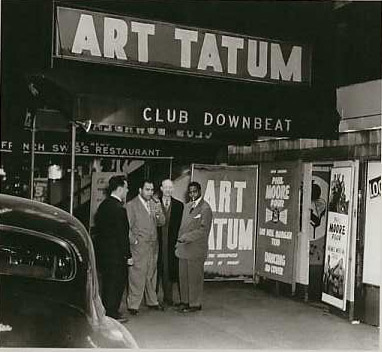

That got my attention. Art Tatum, after all, is generally thought to be the greatest of all jazz pianists. George Gershwin and Vladimir Horowitz used to go to after-hours clubs to hear him play, and Fats Waller is said to have introduced him from the bandstand as follows: “Ladies and gentlemen, I play piano, but God is in the house tonight.” To be sure, I’d never heard Tatum live—he died ten months after I was born—but I owned more than enough of his records to know how special he was, and I found it unlikely in the highest degree that an old man who spent his Saturday nights taking requests from drunks at a suburban pizza parlor could play half as well as Art Tatum had played on the worst day of his brief life.

I brushed Pam off the first time she tried to talk me into going to Shakey’s to hear Harry, but she kept after me, insisting that he really was that good. In the end, it was sheer exasperation that finally made me give in: I was fond of Pam, but I had to show her that I knew better.

“All right,” I said. “You win. Let’s go hear your friend Harry.”

“How about Saturday night?” she replied.

Pam, Dee Dee, and I drove out to Shakey’s that Saturday. The dining room was dark and more than half empty. We ordered a pizza and sat down on a bench next to a tiny bandstand where two men seated on barrels and dressed in white shirts with garters and string ties were rippling through Nola, a once-popular novelty piano solo composed by Felix Arndt in 1915. Epp was a short, bullet-headed man with a big nose. His banjo, which he strummed skillfully and with visible and infectious pleasure, was fitted out with flashing colored lights. All I could tell about the man at the piano was that he had a broad back and that his playing was clean, straightforward, and ragtimey. As for his piano, it was a battered upright that looked as if it had been bought at a garage sale for a sum in the low two figures.

Harry turned around on his barrel and said hello to Pam and Dee Dee in a cheerful midwestern twang. He had a massive head and wore a pair of horn-rimmed glasses with one opaque lens. “What do you kids want to hear?” he asked.

“How about ‘Sweet Lorraine’?” I said with carefully studied casualness. “Sweet Lorraine” was a Tatum standby, and I hoped that it would prove my point to Pam without bringing needless embarrassment to the friendly man at the piano.

Was it something in the tone of my voice? Had Pam and Dee Dee tipped Harry off that there was a skeptic in the house? Or was it just that Shakey’s was nearly emptied out for the night and that he felt like playing to suit himself? I don’t know—I never asked him—but I remember the smile he flashed at me, an irresistible mixture of good humor and a mouth full of gold teeth that gave off more light than Epp’s banjo. “Sure,” he said, “glad to oblige.”

Harry spun round on his barrel and settled his heavy hands on the yellowed keys of the old upright. I leaned back and crossed my arms as he began to play, note for note, the introduction to Art Tatum’s 1940 recording of “Sweet Lorraine.” Then, with Epp strumming softly in the background, he moved gracefully from the impressive to the impossible: he launched into an original improvisation on “Sweet Lorraine” in the style of Art Tatum. This was the way Tatum might have played the song—the same rich, full tone, the same fluttering downward runs, the same iridescent harmonies—only Harry was making it all up on the spot.

My head began to spin. I felt myself in the presence of something inexplicable, perhaps even supernatural. It was as though the spirit of the world’s greatest jazz pianist had somehow taken up residence in the body of an aging, half-blind white man from Independence, Missouri.

Harry wrapped up the song and turned around once more to take a seated bow. Pam and Dee Dee clapped enthusiastically. I sat there with my mouth hanging open. Then I pulled myself together and asked him to play “Tea for Two,” another Tatum specialty. He laughed and said he’d be delighted. Harry and Epp spent the next hour taking our requests. When the last set was over, I asked if I could bring my bass along and sit in some time. “Oh, sure,” Harry said. “We’d be glad to have you.”

My plan, needless to say, was to come back the very next week and play with the Skinheads for as long as they were willing to put up with me, and that was what I did. I spent the next few months hanging out at Shakey’s whenever I had a free Saturday night, listening and learning and sitting in once or twice each set. I soon discovered that Harry liked to reminisce, and he gradually worked his way through the story of his career in between sets. It seemed that he had first heard Art Tatum on record in the late Thirties, and was so impressed that he resolved to learn how to play like Tatum. That, he told me, was the only way to play the piano. He said this in a matter-of-fact tone of voice, as if to suggest that anyone in the world could learn how to play piano like Tatum if they tried hard enough.

Harry returned to Kansas City after the war and spent several years working as a staff pianist at KMBC, then the biggest radio station in town. (Radio stations still had full-time staff musicians in those days.) Then he became the organist at Royals Stadium, a job he held down until he could no longer see well enough to read the scoreboard. Once that happened, he retired and started gigging with Epp, another old-timer whose ornate banjo playing somehow managed to mesh with Harry’s more modern-sounding virtuosity. He lived alone in a neat frame house and devoted himself to his students, all of whom idolized him.

As I got to know Harry better, I realized that there was far more to him than the fact that he could play piano like Tatum, spectacularly impressive though that was. He was a man of singular sweetness of character. He was also wholly lacking in personal ambition. Though he was vaguely remembered by many of the older players in town, I never met a jazzman under the age of forty who knew his name. I was appalled, but Harry couldn’t have cared less. He had never cut a record and wasn’t interested in doing so. The homemade cassette of old-time songs that he and Epp hawked at Shakey’s every Saturday night was good enough for him. His idea of a really good time was to stay home and listen to records by his three favorite piano players: Erroll Garner, Nat Cole, and Tatum.

I found it hard to understand Harry’s lack of ambition, partly because I couldn’t imagine not being ambitious and partly because the hours I spent with him on the bandstand had made me fully aware of how extraordinary a pianist he was. If I’d taped him on one of his better nights and sent the results to a few well-chosen people in New York or Los Angeles, the record companies would have come pounding on his door. But Harry didn’t care enough about fame to pursue it, and I wouldn’t have dreamed of trying to tell him what to do with his life—at least not at first.

It wasn’t long before I started thinking of Harry not as a reclusive genius, the Midwestern counterpart of Peck Kelley, but as a member of the family, a kind of honorary uncle. He wanted to see me get ahead in the tight little world of Kansas City jazz, and I think he came to look upon me as something of a protégé. I found myself turning to him for professional advice, which he was more than glad to give. The only things I wanted from Harry that I was unable to get were things that his retiring temperament made it hard for him to give: I wanted to play real jazz with him, and I wanted to make him a celebrity.

The Skinheads played very little jazz, real or otherwise, at Shakey’s. They ground out five choruses of “Lara’s Theme” for every chorus of “Sweet Lorraine.” That was what the people wanted to hear, and that was what they got. Significantly, Harry and Epp never called themselves jazzmen, at least not in my hearing. They were “commercial musicians,” meaning that they were prepared to play whatever people asked for, so long as they knew, more or less, how it went. It was as simple as that, and as frustrating.

Then Pam and Dee Dee had the brilliant idea of throwing a party at Harry’s house. One Sunday night, a dozen music majors drove out to Independence and took over his music studio, a converted garage that contained a baby grand, a Hammond organ, an overstuffed couch, plenty of chairs, and a thick rug. We supplied the food and drink and I brought along my bass, figuring that the Skinheads would welcome the opportunity to stretch out and swing. It didn’t work out that way, though: Harry’s desire to entertain was so deeply ingrained that he and Epp spent most of the evening accompanying the voice students in show tunes. We all had a marvelous time, Harry included, but hardly any jazz got played.

I was no better at nudging Harry into the spotlight, unable as I was to understand how little he cared to be there. Had some terrible catastrophe left invisible scars on his psyche? Or was it simply that Harry, sure of his own worth, knew that the praise of strangers means nothing next to giving pleasure to a roomful of intimate friends? Whatever the reason, he had no desire whatsoever to “get ahead,” and the conflict between his self-effacing shyness and my inability to accept it led to an uncomfortable episode in which Harry, for the first and only time in the course of our acquaintance, embarrassed me.

By that time, I was writing a weekly jazz column for the Kansas City Star, and I used my influence, such as it was, to persuade a local concert series to book Harry for its spring jazz piano festival. He went along with the idea; he generally went along with anything anybody suggested. Then, to my astonishment, he pulled out three weeks before the concert, explaining that some old friends of his were coming to town that weekend and that he would be too busy to make the gig.

I never tried anything like that again. Incapable of fathoming Harry’s modesty, I learned at last to respect it, and I also came to understand long after the fact that the medium-sized cities of America are full of jazz masters who, like him, are all but unknown. Some are frustrated by their obscurity, others deeply content. Harry was one of the content. His life made me think of a line from Thomas Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”: Full many a flower is born to blush unseen/And waste its sweetness on the desert air. But Harry, unlike Gray, knew better than that. He knew that the sweetness of his painstakingly polished art was not wasted merely because he lavished it on audiences of ten, or one.

That was why I was so surprised when he called me up one afternoon in the spring of 1980. “Terry,” he said, “Epp and I have decided to make another record. That old Skinheads cassette is getting a little tired, and there are some new tunes we want to do.”

“That’s just wonderful, Harry,” I said, meaning every word.

“Well, I’m glad you think so.” He paused. “Oh, there’s one other thing. Would you like to play bass for us? Not your electric bass—I hate that damn thing. Get an old stand-up bass and bring it down to the house next Saturday and we’ll rehearse.” He paused again. “You know, maybe we’ll even find a studio and make a real record one of these days.”

I hung up the phone and started jumping up and down.

I showed up at Harry’s house a few days later. Epp was already there, tuning up a hollow-bodied electric guitar. There was no banjo in sight. I unpacked my bass and slipped a cassette into the tape deck, Harry stomped off “Sweet Georgia Brown,” and all at once he and Epp threw off the shackles of commercial music and started to jump. Harry sounded like a cross between Tatum and Nat Cole, while Epp’s slightly choppy playing became smooth and bluesy, just like Oscar Moore, the guitarist of the King Cole Trio. I stayed in the background, more than content to discreetly accompany two masters at work.

As afternoon gave way to early evening, Epp and I packed up our instruments and made ready to head for home. For once, I didn’t think about how I was going to make Harry Jenks famous. All I cared about was the sheer pleasure of playing, and the prospect of doing it again. I plucked my cassette out of the tape deck and slipped it into the pocket of my windbreaker. We didn’t bother to make a date for our next rehearsal. There was no hurry.

I rang Harry up a couple of weeks later. When did he want to rehearse again? He sounded enthusiastic, but he also sounded uncomfortable, as if he were in pain. He asked me to hold on for a moment. The phone was silent for two full minutes. Then he came back on the line. “Terry, I’m not feeling well,” he said. “The old stomach is acting up. Something I ate at lunch, I guess. But call me in a couple of days, would you? It’s about time for another rehearsal.”

Pam called the next day to tell me that Harry had died in the night of a bleeding ulcer. I hung up the phone and stared out the window for a long time. Then I sat down and wrote a new draft of my next jazz column. It was an obituary, the first one I’d ever written about a person I’d known, and it ended with a reference to the record that would now never be made:

His friends all thought fame finally had Harry pinned down. Instead, he’ll have to settle for the memories of his friends. There were hundreds of them, so perhaps that’s not such a bad monument after all.

A couple of days later, I took the afternoon off and drove out to Independence for Harry’s funeral. The church was large and the parking lot was jammed. Most of the people inside were middle-aged and older, although dozens of Harry’s students showed up as well. Epp and a four-piece band were seated in the choir loft, playing a slow blues. I took no part in the proceedings: I was a recent addition to Harry’s life, and I knew that his funeral belonged to those who had known him longer. I was satisfied with my memories.

The pastor spoke warmly of Harry’s kindness and generosity. Then he told a story. During World War II, he said, Harry had visited New York City on an overnight pass. As soon as he got off the boat, he headed straight for 52nd Street, which in those long-ago days was lined with nightspots, and sat in at the Three Deuces, one of the hottest jazz clubs in town. Art Tatum was sitting at the bar. When Harry finished playing, Tatum strolled up to him and said, “Boy, you play just like me, only you’re white!”

A leathery-faced old man sitting next to me shook his head and smiled. He had heard the story before. I smiled, too, but for a different reason: Harry, modest to a fault, had never bothered to tell me about the night he played for his idol. I suppose he saw no reason to do so, and he was, as usual, right. It would have impressed me, but to no real effect, since I couldn’t have admired Harry, or loved him, any more than I already did.

A decade later, I was sifting through a cardboard box full of long-forgotten mementoes that was tucked in the corner of the bedroom of my tiny New York apartment. To my surprise, I ran across a few relics of my friendship with Harry. I found the column about him that I had written for the Kansas City Star, in all likelihood the first time his name had appeared in print for decades save for the formal obituary that the Star had run a couple of days before. I also found two cassettes. The first one bore a clumsily printed label that said “K.C. Skinheads.” Harry had given it to me after a Saturday-night session at Shakey’s. It contained crudely recorded versions of Epp’s banjo specialties, among them “Dill Pickle Rag,” “Maple Leaf Rag,” “St. Louis Blues,” “Waiting for the Robert E. Lee,” “Havah Nagilah,” “Dueling Banjos,” and (of course) “Nola.” Harry soloed only once or twice, preferring to lay back and accompany Epp with his customary elegance. I remembered how I’d longed for Epp to lay back and let Harry shine. I knew now that Harry had wanted it that way, that this discretion was more characteristic of the Harry Jenks I’d loved than a hundred flashy solos.

The second cassette was blank save for a single word scrawled in pencil on the label: “Harry.” It was, I realized at once, the tape of our lone rehearsal. I’d played it on the night of Harry’s funeral, after which I tossed it into a box and forgot about it. Now I put it on my desk, but I didn’t listen to it. For whatever reason, I couldn’t bring myself to fling wide the door to the fast-receding past.

The cassette was gathering dust on my desk when, a few months later, I finally slipped it into the tape deck and turned up the volume. All at once my living room was full of the joyous sounds of a bright spring day ten years before. There was Harry, batting out “Sweet Georgia Brown” in crisp, twinkling octaves; there was Epp, strumming four steady beats to the bar; there was I, ten years younger, laying down a simple two-beat bass line in the background. I listened to two bald-headed old men and an eager young boy exchanging cries of delight, talking happily between songs about the record they were planning to make, sure that they had all the time in the world in which to make it. Nothing, I thought as I listened, tears at our hearts so much as remembered pleasure. Every bright spring day ends with a grown man standing in his living room years later, shaking his head sadly, knowing at last that there is never, never enough time in the world to do the things that make us happy and be with the people we love.

* * *

Art Tatum plays a solo version of Jerome Kern’s “Yesterdays.” This kinescope, an excerpt from an episode of The Spike Jones Show originally telecast on April 17, 1954, is believed to be the only surviving film footage of Tatum playing piano on television:

Newsreel footage of the Art Tatum Trio playing “Tiny’s Exercise” at the Three Deuces in New York on December 5, 1943, around the time that Harry Jenks met Tatum there. The guitarist is Tiny Grimes and the bassist is Slam Stewart. Part of this footage was included in “Upbeat in Music,” an episode of The March of Time released to theaters in December of 1943: