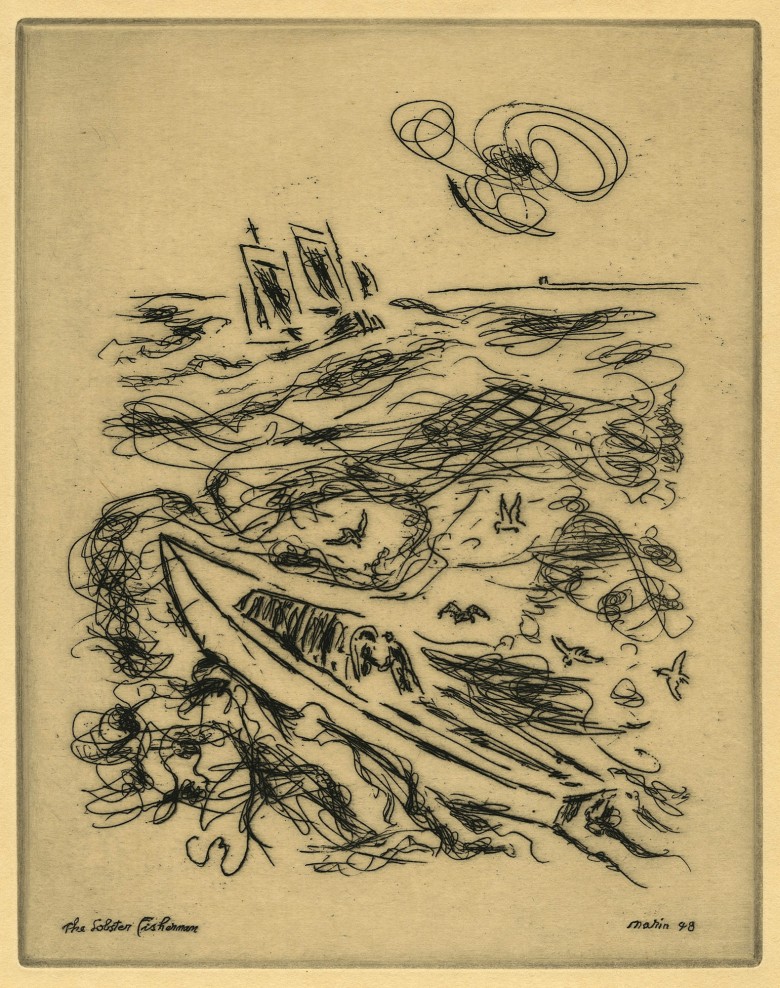

I have trouble keeping secrets from Mrs. T, something that amuses her no end, but I somehow managed to order “The Lobster Fisherman” and get it framed on the sly, and I’m delighted to report that it went over big when I finally brought it home to Connecticut last week.

Marin, America’s first cubist and one of the twentieth-century artists whose work means the most to me, is best remembered today for his watercolors. I use the term “remembered” somewhat loosely, for he is no longer very well known by name, either in this country or elsewhere. Such, however, was not always the case, as I explained when I wrote a column about Marin and his work that ran in The Wall Street Journal back in 2011:

Sooner or later, everyone who writes about John Marin gets around to mentioning the 1948 Look magazine poll of 68 critics, curators and museum directors who, when asked to name America’s greatest living painters, put him at the top of the list. Five years later, the headline of Mr. Marin’s New York Times obituary described him as “Artist Considered by Many as ‘America’s No. 1 Master.’” No less a highbrow than the art critic Clement Greenberg concurred, predicting that Mr. Marin and Jackson Pollock would “compete for recognition as the greatest American painter of the 20th century.”

So why does Mr. Marin so often get the “John Who?” treatment? For it’s better than even money that unless you happen to be a connoisseur of American modernism or an art-history major, his name is unknown to you. It’s been 21 years since a major U.S. museum last put together a full-scale retrospective of his work. New York’s Museum of Modern Art owns 25 Marins—but not a single one of them is currently on view….

Why, then, is Mr. Marin so underappreciated by the art-world elite? The standard explanation is that even though he marched to the edge of abstraction, it seems never to have occurred to him to turn his back on the visible world. “The sea that I paint may not be the sea,” he wrote, “but it is a sea—not an abstraction.” After the rise of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s, his deep-rooted belief in representation came to be seen as old-fashioned, even quaint.

Nothing, alas, has changed since then: Marin remains the most underappreciated of American masters. The good news, however, is that this makes him more affordable to those of us who know his worth. To be sure, Marin’s watercolors are well above my pay grade, but his best etchings are precisely comparable in quality, and the two that I love most, “Downtown. The El” and “The Lobster Fisherman,” happen to have been printed in larger-than-usual editions, thus making them accessible to collectors of modest means. In addition, these two etchings represent between them his favorite subjects: the first is an urban cityscape, the second a marine study. To own them both, then, is to own a Marin Museum in miniature.

Not surprisingly, “Downtown. The El” was one of the very first pieces of art that I bought, a couple of years before I met Mrs. T. I wrote about the purchase in 2003, on the day that this blog first went live:I just bought a copy of John Marin’s 1921 etching “Downtown. The El,” and it’s a beauty—a nervous cubist spiderweb that captures some of the sheer excitement of this crazy city in which I insist on living. It’s already taught me a lesson, which is that the ultimate test of the quality of a work of art is whether you can look at it every day without getting bored or irritated. So far, so good.

“Downtown. The El” now hangs over the couch in our Manhattan living room, and I look at it as often and as appreciatively today as I did sixteen years ago. For some reason, though, it never occurred to me to buy a copy of “The Lobster Fisherman” until I realized that it would make an ideal present for Mrs. T, a bred-in-the-bone New England girl who loves lobster and everything to do with its catching and cooking as much as she does modern art.

I started searching, and within a couple of weeks I’d found a flawless, richly inked impression of “The Lobster Fisherman,” one whose only “defect” made it an even more attractive purchase. Marin, it seems, never got around to pencil-signing this particular copy, an oversight that erased a zero from the end of the price tag—and yes, we’re talking three figures, in case you’re wondering whether you can afford to buy real art. Believe me, you can. (I knocked down the exquisite 1888 Berthe Morisot etching in the hall of our Manhattan apartment for a hundred dollars.). Now Mrs. T is happily fussing over where to hang it.

For those of you interested in such things, “The Lobster Fisherman,” which was etched in 1948 and printed two years later in an edition of 125, is based on a much lesser-known oil canvas of the same name that Marin also painted in 1948. (Its present whereabouts are unknown, at least to me.)

As is not infrequently the case with prints that have been based on pre-existing paintings, the etching reduces the painting to a simpler, even more immediately arresting image, an electric tangle of scrawled lines of black ink that puts me in mind of what an anonymous staffer for Life wrote about Marin’s work in 1950:

His scenes of the Maine coast, sailing ships and towering city skylines are never entirely realistic yet never unrecognizably abstract. They are glimpses into a single moment—the jostling of a city mob or the whipping of the wind through a schooner’s rigging.

Mrs. T and I lost our hearts to the coast of Maine the first time we went there, but until now we had yet to acquire a piece of art that reminded us of how we feel about it. (This one, for instance, always makes us think of our many visits to New York’s Hudson Valley.) Whenever we look at “The Lobster Fisherman,” I expect it will fill us both with memories of some of the best times we’ve spent together. This, too, is one of the special joys of living with art.

For the record, copies of “The Lobster Fisherman” are also owned by the Georgia Museum of Art, Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts, New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art, Washington’s National Gallery of Art, Phillips Collection, and Smithsonian American Art Museum, and in the John Marin Collection of Maine’s Colby College Museum of Art. I have yet to see it hanging in any of those fine institutions, though, and I doubt they care about their copies as much as the curator of the Connecticut branch of the Teachout Museum will henceforth care about hers.