William Jewell College, my alma mater, recognizes its alumni each year on Achievement Day, when it presents a group of “exemplary graduates” with the Citation for Achievement Award, the school’s highest honor, which I received in 2000. This being the seventy-fifth anniversary of Achievement Day, Jewell decided to commemorate the occasion last week by inviting all of its past “achievers” to a banquet at which, among other things, two of us would perform. Daniel Belcher, a classical baritone who specializes in new music—his best-known role is that of Prior Walter in Peter Eötvös’ 2004 operatic version of Angels in America—was asked to sing, and I was asked to lecture about what I’d learned from my career as a writer.

The invitation was an honor in and of itself, one that I wanted very much to accept. By the time I heard from Jewell, though, Mrs. T was already listed for transplant in New York and was being evaluated for listing in Philadelphia. I warned the organizers that were we to get the Big Call at any time prior to the banquet, I might be forced at the last minute to deliver my speech via Skype. They replied that they’d rather have me on a TV screen than not at all, and Mrs. T told me firmly that I should say yes, so I did.

William Jewell College is in Liberty, a suburb of Kansas City, Missouri. I lived in Liberty for four years after graduating, and by the time I finally moved away, I’d become deeply attached to Kansas City and its environs, so much so that I eventually came to think of it as a second home. I still do, but none of my family lives there, meaning that I rarely get a chance to go back and visit. I’ve reviewed a few plays in Kansas City, and I gave a lecture at Jewell six years ago, but for the most part I have no choice but to content myself with my memories of the Midwestern city that was almost as important to my life as Smalltown, U.S.A.

It struck me while driving around town that I felt as though I were playing out the next-to-last scene of Our Town, in which Emily Webb, who has just died in childbirth, is allowed by the Stage Manager to relive a single day of her life, with one caveat: she cannot do anything differently. In my case, I gazed greedily at the still-familiar sights of Liberty and Kansas City, but was unable to step into them. All I could do was see and remember, with Emily’s heartbreaking words tolling in my mind’s ear: I can’t look at everything hard enough.

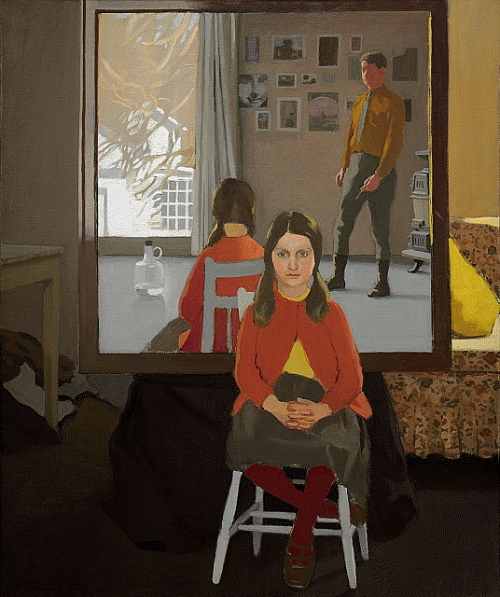

From time to time, past and present joined hands. That happened at the Nelson-Atkins, where I looked at two paintings that have special meaning for me. One was Fairfield Porter’s “The Mirror,” which I saw for the first time when I returned to Kansas City many years ago to write a magazine piece about the local arts scene, an experience that I described in the speech I gave that night:

I didn’t know anything about Porter, but I liked what I saw, so I went to the bookstore of the Nelson-Atkins and bought a copy of a book he wrote called Art in Its Own Terms. As I flipped through the pages in my hotel room that night, I ran across this sentence: “When I paint, I think that what would satisfy me is to express what Bonnard said Renoir told him: make everything more beautiful.” Never in my life have I read a sentence that landed harder than that one: Make everything more beautiful. All at once, I knew what my life was and would be about.

The other was Willem de Kooning’s “Woman IV,” which was left to the Nelson-Atkins by William Inge, a marvelous piece of art-history trivia that had lodged in my memory long, long ago, waiting patiently to be put to use. Two years ago, I was writing a play about Inge and Tennessee Williams called Billy and Me, the second act of which takes place in Inge’s New York apartment. As I tried to envision how the set might look, I remembered that Inge had once owned “Woman IV,” and that it hung in his Sutton Place home for a time before ending up in Kansas City. Rebecca Pancoast, Palm Beach Dramaworks’ scene painter, subsequently made a slightly larger-than-life copy of “Woman IV” that was used as the centerpiece for the second act. Now I was looking at the real “Woman IV” for the first time since writing Billy and Me, marveling as I did so at the fantastic chain of coincidence that had led me from Kansas City to New York to West Palm Beach and back again.

A few hours later, I stood up in front of a ballroom full of loyal alumni and friends of the college to give a speech called, appropriately enough, “The Lesson of Satchmo,” in which I spoke of what I had learned from spending the past decade and a half of my life thinking and writing about Louis Armstrong. I adjusted the microphone, looked out at the crowd, and saw the upturned faces of some of the friends and teachers I had met for the first time half a lifetime ago.

I glanced quickly at the words printed on the page before me: I am what I am because, once upon a time, I came here and did what I did. Then I took a deep breath and began to speak.

* * *

To hear Gina Kaufmann interviewing me on KCUR’s Central Standard, go here. (My segment of the program starts at 28:29.)My Achievement Day speech:

The last two sentences of my speech are inaudible on the video. This is what I said as the music heard on the soundtrack was playing:

I’m done talking, but it wouldn’t be right to wrap this speech up without listening to the voice of the man himself. So if I may, allow me to play a snippet of the song that brings Satchmo at the Waldorf to a close.

* * *

Mary Martin plays the role of Emily in the next-to-last scene from Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. The scene is introduced by Oscar Hammerstein II, who also plays the role of the Stage Manager. This performance was originally seen on The Ford 50th Anniversary Show, directed by Jerome Robbins and simulcast by CBS and NBC on June 15, 1953: