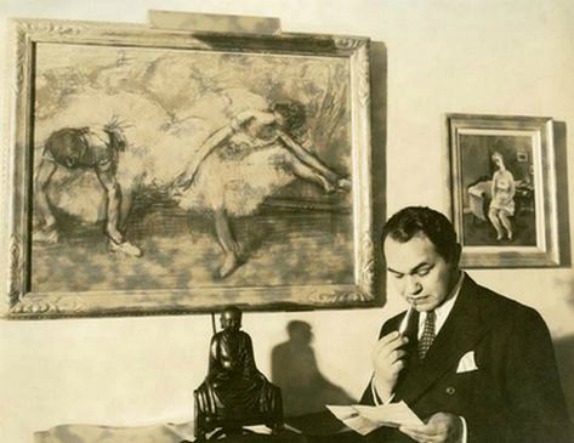

As I pointed out in my Journal piece, Robinson was by way of being an all-around aesthete:

A classically trained stage actor and classical-music buff—his friends included George Gershwin and Igor Stravinsky—he started purchasing Impressionist and Post-Impressionist canvases in earnest on a 1936 trip to Europe, five years after “Little Caesar” made him a superstar. Eight years later, he built his own private gallery to house the hundred-odd paintings in his collection. New York’s Museum of Modern Art and Washington’s National Gallery exhibited 40 of them in 1953, and the lineup included Bonnard, Cézanne, Degas, Gauguin, Matisse, Picasso, Renoir and Van Gogh.

What began as a hobby turned into a compulsion, so much so that he and his first wife and son sat in 1939 for Édouard Vuillard, who did a pastel portrait of them. “It is short of a masterwork,” Robinson cheerfully admitted. “Paintings on commission usually are. But it beats hell out of a Kodak snapshot.”

“La famille d’Edward G. Robinson” was still in private hands when I wrote that column, and I was unable to locate an online reproduction, which made it impossible for me to write about it any more specifically. Still, I couldn’t help but wonder how good it really was, and I was especially curious to know what Vuillard, who evolved late in life into an important (and well-compensated) society portraitist, had made out of Robinson’s ferociously distinctive bulldog features.

A couple of nights ago, Mrs. T and I were watching an old Robinson film, Brother Orchid. All at once a light went on in my head, and I opened my laptop and started searching for “La famille d’Edward G. Robinson.” To my amazement and delight, I managed to track down within a matter of seconds what Paul Harvey used to call “the rest of the story.” It turns out that two months after my column appeared in the Journal, the owners of the pastel gave it to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, which has since posted an image on its website, coupled with a complete provenance:

1939, commissioned by Edward G. Robinson (b. 1893 – d. 1973), Beverly Hills, CA; about 1956, passed to his former wife, Gladys Lloyd Robinson (b. 1895 – d. 1971), Los Angeles; October 26, 1960, Gladys Lloyd Robinson sale, Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, lot 81, sold. 1985, Nathan Cummings (b. 1896 – d. 1985), New York; November 13, 1985, Cummings estate sale, Christie’s, New York, lot 115, sold. 1987, sold by Hilde Gerst Gallery, New York, to Mr. and Mrs. Stephen Weiner, Boston; 2015, gift of Mr. and Mrs. Weiner to the MFA. (Accession Date: September 24, 2015)

“Passed to his former wife” is a euphemism: Robinson was forced to sell off most of his collection in 1956 as part of a nasty divorce settlement, though he managed to assemble another, similarly impressive one prior to his death in 1973. But he seems not to have made any effort to buy back “La famille d’Edward G. Robinson,” and it’s easy to see why when you look at the pastel, in which his ex-wife figures very prominently. I doubt he much cared to be reminded of her.

Vuillard’s late portraits aren’t as admired as they ought to be, as I pointed out when I reviewed a 2003 National Gallery of Art retrospective of his work:Guy Cogeval, general curator of “Edouard Vuillard,” has also sought to refute the widespread notion that Vuillard spent the last two decades of his life (he died in 1940) doing little but turning out judiciously flattering society portraits. I don’t see how anyone can hold to so rigidly dismissive a view of late Vuillard after seeing his tough-minded, even harsh 1933 painting of the couturier Jeanne Lanvin in her Paris office. The hard, unflattering glamour with which he portrays this aging doyenne of fashion is reminiscent of Sargent, another great portrait painter whose psychological acuteness has often been overlooked by critics obsessed with his well-to-do clientele.

Would that “La famille d’Edward G. Robinson” had been part of that show! I would have enjoyed pointing out that Vuillard placed the world-famous actor at the extreme left edge of his group portrait, cropping his head and body so that they are not quite fully visible. Might that have been an obliquely witty reference to his subject’s celebrity? We cannot know: Robinson’s brief mention of the pastel in his autobiography is, so far as I know, the only thing that has ever been written about it until now. In any case, it pleases me greatly that “La famille d’Edward G. Robinson” has finally resurfaced, and I hope to take a look at it the next time I’m in Boston. Alas, it’s not presently on view, but perhaps I can manage to nudge the MFA into hanging it.

Entirely aside from the fact that Vuillard’s pastel is an unpretentiously lovely piece of work, I can’t think offhand of very many other paintings by great artists—Andy Warhol and Norman Rockwell don’t really count—of equally great movie stars. Top-tier artists, it seems, have tended not to be drawn to film stars as subject matter, though there are several noteworthy exceptions to the rule. John Singer Sargent sketched John Barrymore in 1923, Marc Chagall painted Charlie Chaplin in 1929, and Salvador Dalí did portraits of Shirley Temple, Laurence Olivier, and Harpo Marx (the first two of which aren’t very good, in my opinion, but there’s no accounting for taste). More recently, and consequentially, Willem de Kooning’s Marilyn Monroe, painted in 1954, is all of a piece with his “Woman” series, arguably his most important body of work. As for sculptors, a friend reminds me that Isamu Noguchi made a charming bust of Ginger Rogers in 1941 that is now owned by the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery.

Nevertheless, these exceptions are exceptions to a rule that has otherwise held pretty firm throughout the first century of movie stardom. It makes me wonder whether major artists (photographers self-evidently excluded) are disinclined by nature to devote time and energy to portraying faces so ubiquitous and familiar as to necessarily resist the profound imaginative transformation that is the essence of great art. If so, though, it’s surely at least as revealing that no other movie stars, so far as I know, seem ever to have thought to commission portraits from artists comparable in stature to, say, Vuillard or Noguchi.

Whatever the explanation, “La famille d’Edward G. Robinson” is a work of real distinction, one of a handful of its kind, and for that reason alone, it deserves to see the light of day. Here’s hoping!