I went to see a play in Rhode Island last Monday. I’d planned to bring Mrs. T with me, but she was under the weather when the time came to hit the road, so I ended up going by myself, leaving early enough to dine before the show at a restaurant directly across the street from the theater. I know how to eat alone—I brought a book—but it isn’t any fun, and I suspect my waitress sensed that I was both lonely and a bit blue, because she was unusually kind and considerate to me. When I got home, I decided to send her a thank-you note. It took me a minute and a half to track her down on Facebook, and within an hour I’d heard back from her. Sure enough, she proved to be as friendly as I’d thought. For me, this isn’t all that unusual a story: I “met” several of my best friends on Twitter before getting to know them in person. But it also reminded me of the many doubts I continue to harbor about the digitally connected world into which I’ve survived.

I’ve been something of a public figure ever since I started writing about classical music for the Kansas City Star when I was an undergraduate, so I’ve had plenty of time to get used to the exigencies of living out loud. When I started blogging a decade and a half ago, I took for granted that it would be essential to draw a bright line between the things I talked about on line and the things I kept to myself. I observed the same precaution when, later on, I started using Twitter and Facebook. The “Terry Teachout” who blogs and tweets each day is a partial portrait of the real me, true as far as it goes but in no way the whole story of who I am and what I think.

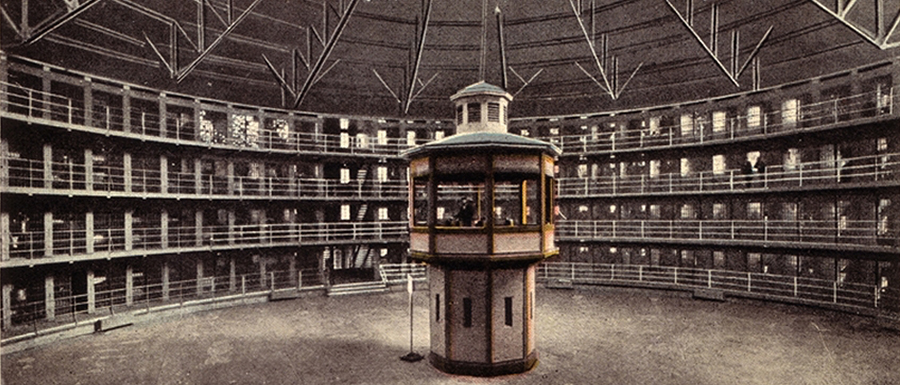

Many of my millennial friends, by contrast, seem not to draw that distinction. They disclose themselves on line to a degree that I find startling. I wonder whether they’ll come to regret this openness later on in life. Perhaps not: it may well be that they no longer have any expectation of privacy, and so cannot imagine having any inviolable secrets. Perhaps they’re wise to accept our brave new world of total accessibility as it is.

Perhaps—but I doubt it, just as I doubt that the ubiquity of smartphones is a good thing for the human race. So did Oliver Sacks, who wrote an essay that was posthumously published in The New Yorker the other day in which he expressed grave reservations about the way we live now:Everything is public now, potentially: one’s thoughts, one’s photos, one’s movements, one’s purchases. There is no privacy and apparently little desire for it in a world devoted to non-stop use of social media. Every minute, every second, has to be spent with one’s device clutched in one’s hand. Those trapped in this virtual world are never alone, never able to concentrate and appreciate in their own way, silently. They have given up, to a great extent, the amenities and achievements of civilization: solitude and leisure, the sanction to be oneself, truly absorbed, whether in contemplating a work of art, a scientific theory, a sunset, or the face of one’s beloved….

A few years ago, I was invited to join a panel discussion about information and communication in the twenty-first century. One of the panelists, an Internet pioneer, said proudly that his young daughter surfed the Web twelve hours a day and had access to a breadth and range of information that no one from a previous generation could have imagined. I asked whether she had read any of Jane Austen’s novels, or any classic novel. When he said that she hadn’t, I wondered aloud whether she would then have a solid understanding of human nature or of society, and suggested that while she might be stocked with wide-ranging information, that was different from knowledge. Half the audience cheered; the other half booed.

I am, however, old enough to have a fully matured appreciation of the Law of Unintended Consequences, and I’m similarly appreciative of the Spanish benediction that one of Patrick O’Brian’s fictional characters cites with approval: “May no new thing arise.” It’s good advice—except when it isn’t. The trick, ever and always, is to have the wisdom to know the difference.