“Patience, n. A minor form of despair, disguised as a virtue.”

Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“Patience, n. A minor form of despair, disguised as a virtue.”

Ambrose Bierce, The Devil’s Dictionary

Ricardo Montalban “plays” “Fantasia Mexicana,” Johnny Green’s arrangement for piano and orchestra of Aaron Copland’s El Salón Mexico, in Fiesta, a 1947 film directed by Richard Thorpe. Montalban’s playing is dubbed by André Previn:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“Suffering is admittedly one of the central problems of human existence; but this is because we have a suspicion that it is all for nothing. If we had a certainty about meaning, the suffering would be bearable. With no certainty of meaning, even comfort begins to feel futile.”

Colin Wilson, Frankenstein’s Castle

* * *

Careerwise, Tarell Alvin McCraney is as hot as it gets. Not only did “Moonlight,” whose screenplay was adapted from one of his unpublished stage plays, clean up at the Oscars in 2017, but “Choir Boy,” a gay coming-of-age play that just transferredto Broadway after a highly acclaimed off-Broadway run, received rapturous reviews, has extended its limited run and is expected to be a top Tony contender. But unanimous critical enthusiasm sometimes means there’s less to a show than meets the eye, and having seen “Choir Boy” after the reviews came out, I can’t claim to be altogether surprised that it’s a paper-thin piece of work.

“Choir Boy” tells the story of Pharus (normally played by Jeremy Pope), an “effeminate” student (Mr. McCraney’s word) at an all-black, all-male prep school who is Wrestling With His Sexuality. It’s the kind of play that is its own spoiler alert: No sooner does Mr. McCraney deal the cards than you know how he’ll be playing them for the rest of the evening. We learn a half-minute after the curtain goes up that Pharus, the head of the school’s prestigious choir, is being tormented by a homophobic chorister who calls him a “sissy” and worse—much, much worse—in the middle of a public performance. From then on, everything that happens is so self-evident that further synopsis is superfluous.

It doesn’t help that Mr. McCraney’s characterizations are as lazy as his plot is familiar….

To the extent that “Choir Boy” is worth seeing, it’s mainly because of Trip Cullman’s staging—every dramatic gesture hits its target with preternatural precision—and his marvelous ensemble cast….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Fred Astaire is interviewed by Michael Parkinson in 1976. This clip is an excerpt from an episode of Parkinson, originally telecast by the BBC on February 14, 1976:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“Waiting is still an occupation. It is having nothing to wait for that is terrible.”

Cesare Pavese, This Business of Living

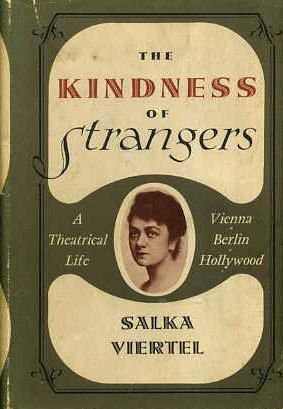

In my new Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, which I resume this week after a hiatus caused by Mrs. T’s recent illness, I write about the reissue of The Kindness of Strangers, Salka Viertel’s memoir of her life in Europe and Hollywood. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

If history is a black comedy—a possibility that I find increasingly probable—then one of the chief sources of its humor is the law of unintended consequences. I doubt, for instance, that it ever occurred to Adolf Hitler that his murderous reign would cause a large number of Jewish artists to flee to and settle in the United States, in the process transforming American culture, high and popular alike.

One of the most remarkable of these émigrés was Salka Viertel, an Austrian stage actor who moved to Los Angeles in 1928, opting to stay there permanently after Hitler came to power. “Neither beautiful nor young enough” (in her own crisp words) to be a movie star, Viertel instead set up shop as a screenwriter, making a sizable chunk of money by working on five of Greta Garbo’s films, including “Anna Karenina.” She then used much of it to help other Jewish artists get out of Europe, come to America and restart their lives in the strange land that was studio-era Hollywood.

Garbo urged Viertel to tell her story in print, and in 1969 she published an autobiography called “The Kindness of Strangers” in which she wrote about her life in Europe and America up through 1954 (she died in 1978). Well received by critics, Viertel’s book subsequently slipped through the cracks of renown. Now, though, it has been reprinted by New York Review Books, which specializes in just such off-center titles…For reasons not obvious to me, this edition has been shorn of the book’s original subtitle, “A Theatrical Life/Vienna-Berlin-Hollywood,” which was at once usefully descriptive and a bit too restrictive. In fact, Viertel’s adventures in Hollywoodland occupy only the second half of “The Kindness of Strangers,” which is in any case far more than just a theatrical memoir. It is also, like Stefan Zweig’s “The World of Yesterday,” a richly detailed, deeply affecting portrait of the lost world of Europe between the two great wars that tore it to pieces.

Even before she moved to the U.S. and launched the now-legendary salon to which the members of Hollywood’s German-speaking colony flocked every Sunday, Salka Viertel was the kind of person who had an uncanny knack for meeting everybody who was anybody….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

“But the real, tremendous truth is this: suffering serves no purpose whatever.”

Cesare Pavese, This Business of Living

An ArtsJournal Blog