Most of the time I can’t quite grasp the undeniable fact that I’m sixty-two, going on sixty-three. Rarely if ever do I feel that old, and I know I don’t look anything like my age (unless my friends and acquaintances have all joined together in a conspiracy to deceive me).

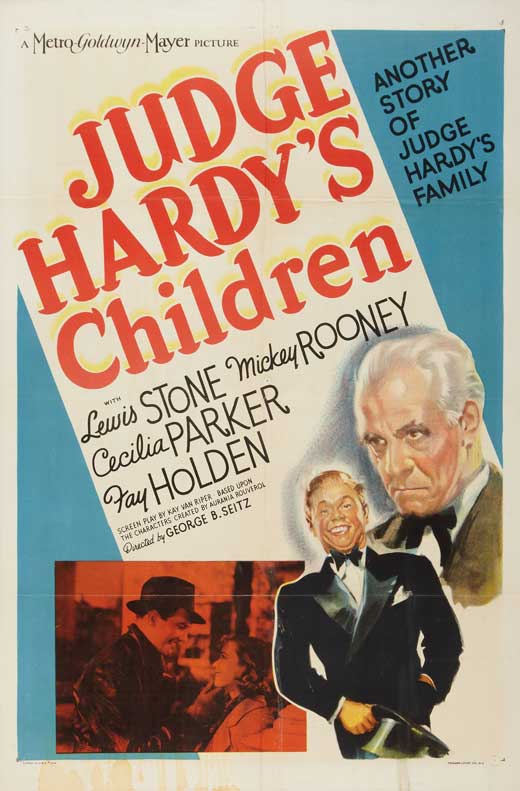

Maybe I should try harder to do so. Mrs. T and I spend a lot of time watching golden-age Hollywood movies, and one of the things that she likes to point out is the frequency with which characters who are presumably in their fifties look and act at least twenty years older than they really are. I expect the Great Depression had something to do with it—I know that it aged both of my mother’s parents far beyond their years—but so, too, does the fact that many of our latter-day male movie stars look positively adolescent. Whatever the reason, I don’t feel nearly as old as I am. Nevertheless, nobody has to remind me that I’ve turned onto the exit ramp that leads inexorably from late middle age to…well, something else.

You know you’re not young anymore when you find yourself spending more and more time thinking about the deaths of friends and loved ones, and that has happened to me. By now, of course, I’ve grown almost accustomed to their loss (“Man gets used to everything—the beast!”). But there are other signs of the times, less jolting but similarly noteworthy, that also have a way of sneaking up on people of a certain age.

Just the other day, for instance, I learned from a Facebook posting that the old Holiday Inn on the outskirts of Smalltown, U.S.A., a structure that I remember very well, was torn down back in September. Not that many of the current residents of Smalltown thought of it as “the old Holiday Inn,” for it had changed hands at least three times since I moved away, ending its longish life as a Days Inn. It was, however, a Holiday Inn when it was built in 1964, and as such it was for a time the fanciest motel in town. (Only a small-town boy like me can use the phrase “the fanciest motel in town” without a trace of irony.)

For a long time, the Holiday Inn’s restaurant was one of Smalltown’s most highly regarded lunch-and-dinner spots, enough so that when my brother and I decided to throw a surprise party for my parents on their fortieth wedding anniversary, we naturally held it there. Moreover, Sour Mash, the country band with which I played bass back in my high-school days, gigged in the same restaurant once a week. It was the first time in my life that I was ever paid hard cash money for making music, and I have no trouble whatsoever recalling how sinfully proud I was to be able at last to call myself a professional musician.

I wrote about both of these things in the memoir of my childhood and youth that I published in 1991:Sour Mash used to play dinner music in the restaurant on Wednesday nights. We each got five dollars a night, plus tips and one free trip through the buffet line. (Seconds were extra for the help.) Forty years to the day after my mother and father were married, they showed up at the Holiday Inn for dinner, pulled open an unmarked door and found, to their amazement, a room full of family and friends gathered around a table loaded with punch and homemade hors d’oeuvres. The light fixtures were covered with blue crepe paper and a phonograph in the corner played Artie Shaw’s 1938 recording of “Begin the Beguine.” Standing in the doorway were my brother and his wife, who had spent three months planning the party, and my wife and I, who had flown to St. Louis and slipped into Sikeston the night before. I snapped a picture of my father as he opened the door and saw us standing there. It was the second time in my life that I caught him completely off guard. The first time was the day I told him I was moving to New York.

That was thirty-two years ago. I don’t like to think about how many of the guests at that glorious, never-to-be-forgotten party are dead now. Most of them, I suspect, including my parents, both of whom I think about every day and miss more than I ever thought possible. I suppose I always took it for granted that I would outlive them. Yet strange as it sounds, there was nothing real about that perfectly logical expectation. In my heart, I must have assumed that they’d always be around, never once stopping to figure the odds against it, much less to imagine exactly how it would feel not to be able to pick up the phone and hear their voices. Yet now they’re dust, just like the old Holiday Inn.

Fortunately, I’m still around, as is my beloved Mrs. T, though we were both having our doubts about her as recently as a couple of weeks ago. If you follow me on Twitter, you’ll know that she got out of the hospital last Thursday and has since been resting comfortably at our Connecticut farmhouse. She’s frail, of course, and will remain so until she gets the pair of new lungs for which we’re waiting and hoping impatiently. But she’s still very much herself, tough and funny and game, and it is the joy of my late middle age—or whatever—to be able to make the waiting easier for her.

No, we’re not young anymore, but…we’re here.

* * *

Julie Wilson and William Roy perform Stephen Sondheim’s “I’m Still Here” (from Follies) in an undated film clip: