One of the nicest things about having spent the past fifteen years covering theater for The Wall Street Journal is that I’ve been able to watch a number of exceptionally gifted artists change and grow over extended spans of time. It happens, for example, that I witnessed Zoe Kazan’s professional stage debut in a 2006 off-Broadway revival of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. I was so struck by her performance, which I described in my review as “nothing short of remarkable,” that I resolved to make a point of keeping up with her developing career. Since then, I’ve reviewed pretty much everything that she’s done on stage in New York, including two of her own plays, and I feel something not unlike pride in her emergence as an artist of the first rank.

One of the nicest things about having spent the past fifteen years covering theater for The Wall Street Journal is that I’ve been able to watch a number of exceptionally gifted artists change and grow over extended spans of time. It happens, for example, that I witnessed Zoe Kazan’s professional stage debut in a 2006 off-Broadway revival of The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie. I was so struck by her performance, which I described in my review as “nothing short of remarkable,” that I resolved to make a point of keeping up with her developing career. Since then, I’ve reviewed pretty much everything that she’s done on stage in New York, including two of her own plays, and I feel something not unlike pride in her emergence as an artist of the first rank.

For Kazan, who is thirty-five, those twelve years add up to a long time—nearly a third of her life to date. For a sexagenarian like me, though, it’s not nearly so long, and it surprised me to realize that so much time had gone by since I’d first seen her on stage. This, I suspect, is part of what what it means to have entered the sixth of Shakespeare’s seven ages of man: rightly or wrongly, I’ve come to think of everything that’s occurred since 9/11 as part of “the recent past.” Those events that predate the coming of the twenty-first century, on the other hand, all seem to me to have taken place “a long time ago.”

No doubt this bifurcated point of view has something to do with the fact that my own recent past has been unusually, even improbably eventful. But it’s also true that once you turn fifty, you start the downhill run: your life is half over at best, and you pick up more and more speed as you go. Small wonder, then, that everything that’s happened to me since 2001 seems to have happened both recently and simultaneously, whereas all previous events—my father’s death, for instance—are equally distant, walled off in my memory by 9/11, the Great Divide that cleaved in twain the lives of my generation, just as the Kennedy assassination and Pearl Harbor did to those Americans who preceded us.

What inspired this train of thought, strangely enough, was the announcement the other day of the bankruptcy of Sears, Roebuck, a half-forgotten company that played no part in my post-9/11 life but once was central to my life as a small-town boy.

What inspired this train of thought, strangely enough, was the announcement the other day of the bankruptcy of Sears, Roebuck, a half-forgotten company that played no part in my post-9/11 life but once was central to my life as a small-town boy.

Many epitaphs have since been written for the Sears that used to be, none of them better than that of Rod Dreher:

Sears was once part of American life—and an American childhood—in a way that is difficult for kids today to appreciate. Sure, it was as ubiquitous as Amazon is today, but the quality of the Amazon experience is fundamentally different. Sears was a place. As a child growing up in the ’70s, I was about as aware of Sears as a fish is of water. It’s just where your mom took you to buy Toughskins jeans for school, and Kenmore appliances, and where your dad got his Craftsman tools. For Baby Boomers and Gen Xers, those brand names convey institutional trust.

Do kids today feel the same way about brands? Does anybody? Those words, and everything about Sears, were bound to an unstated middle American, mid-century ideal. Now that Sears is gone—and in truth, it’s been gone for a long time—it’s hard to find the words to describe a cultural phenomenon that was so defining….

It’s easy to laugh now, but for a rural kid—at least a rural kid like me—that really meant something. It was an escape from the plainness of country life, and an immersion in cosmopolitanism. Sears, cosmopolitan? For me, it absolutely was. Going to Sears was the only reason we ever went into the city. It was like going to a fair, to a bazaar. After I finished dutifully trying on the Toughskins (size “husky”), I was free to wander the entire store alone. Can you imagine letting your nine-year-old wander a large department store alone? Everybody did in those days. It was freedom, it was color, it was a particular kind of wonder that, for a boy like me, was only available at Sears.

I know exactly what Rod is talking about. Back then, of course, Sears mostly meant new clothes to me, and continued to do so well into my college days. But it was the annual Christmas catalogue that epitomized the role played by Sears in shaping the imaginations of kids like us. When I wrote about Christmas in Smalltown, U.S.A., in my memoir of a Missouri childhood, one of the things that I went out of my way to mention was the thrilling ritual attendant upon the arrival each fall of the Sears “Wish Book”:

I know exactly what Rod is talking about. Back then, of course, Sears mostly meant new clothes to me, and continued to do so well into my college days. But it was the annual Christmas catalogue that epitomized the role played by Sears in shaping the imaginations of kids like us. When I wrote about Christmas in Smalltown, U.S.A., in my memoir of a Missouri childhood, one of the things that I went out of my way to mention was the thrilling ritual attendant upon the arrival each fall of the Sears “Wish Book”:

On the day that the Christmas catalogue came in the mail, I sat down with a sharp pencil and a pile of notebook paper and wrote down the name, price, and page number of each and every toy I could possibly want. Then I spent hours paring my list down to a reasonable length, a process that called for clear thinking and a cool head. If the list was too long, I might not get the toys I wanted most; if it was too short, I might get fewer toys than my brother David. (Neither catastrophe had ever happened before, but I figured I had to be ready for anything.)

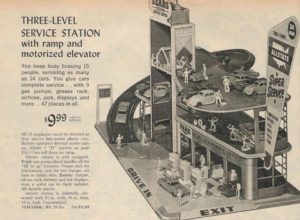

Thanks to the internet, that matchless enabler of nostalgia, it’s possible to flip at leisure through painstakingly scanned electronic copies of the Wish Books of your youth and gaze lovingly upon the toys that you found (if you were lucky) under the family Christmas tree. No sooner did I stumble across Wishbookweb.com than I started looking for my favorite of all the toys that Santa Claus brought to me once upon a time. I found it, too, the “THREE-LEVEL SERVICE STATION with ramp and motorized elevator” for which my father, unbeknownst to me, paid $9.99, about eighty dollars in today’s money, a serious chunk of change for a hardware-store manager circa 1962. I hope he got his money’s worth from watching me play with it. I’ve no idea where it ended up—the junkyard, probably. What I do know is that no Christmas present has ever delighted me more.

Thanks to the internet, that matchless enabler of nostalgia, it’s possible to flip at leisure through painstakingly scanned electronic copies of the Wish Books of your youth and gaze lovingly upon the toys that you found (if you were lucky) under the family Christmas tree. No sooner did I stumble across Wishbookweb.com than I started looking for my favorite of all the toys that Santa Claus brought to me once upon a time. I found it, too, the “THREE-LEVEL SERVICE STATION with ramp and motorized elevator” for which my father, unbeknownst to me, paid $9.99, about eighty dollars in today’s money, a serious chunk of change for a hardware-store manager circa 1962. I hope he got his money’s worth from watching me play with it. I’ve no idea where it ended up—the junkyard, probably. What I do know is that no Christmas present has ever delighted me more.

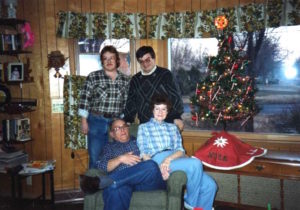

But that was…well, a long time ago. Now the Sears Wish Books belong to the ages, as does my father himself, who was laid to rest in Smalltown’s Garden of Memories in 1998, too soon to know Mrs. T or see Satchmo at the Waldorf or turn on the television and watch the Twin Towers crumble into poisoned dust. Unlike Satchmo, Mrs. T, and my mother, who outlived him by fourteen years, he has become part of my distant past, though no day goes by without my thinking about him.

But that was…well, a long time ago. Now the Sears Wish Books belong to the ages, as does my father himself, who was laid to rest in Smalltown’s Garden of Memories in 1998, too soon to know Mrs. T or see Satchmo at the Waldorf or turn on the television and watch the Twin Towers crumble into poisoned dust. Unlike Satchmo, Mrs. T, and my mother, who outlived him by fourteen years, he has become part of my distant past, though no day goes by without my thinking about him.

Writing that last sentence reminds me of a passage from one of Donald Westlake’s Parker novels in which he describes what it feels like to stab a woman and watch her die:

The world tick-tocked on, and Ellen remained back there in that blood-red second, slowly slumping around the golden hilt.

It was as though he had stabbed her from the rear observation platform of a train that now was rushing away up the track, and he could look out and see her way back there, receding, receding, getting smaller and smaller, less and less important, less and less real. Time was rushing on now, like that rushing train, hurtling him away.

That’s what death is; getting your heel caught in a crack of time.

I cherish my memories of a long time ago, of my father and the Allstate Three-Level Service Station that he bought me and the myriad joys of my mostly happy childhood. Yet I know, too, that I will someday step in my own crack of time, and so I intend to fill the days between now and then with all the brand-new memories that they’ll hold. That’s what I’ve been trying to do ever since 9/11. So far it’s worked out pretty well.

I cherish my memories of a long time ago, of my father and the Allstate Three-Level Service Station that he bought me and the myriad joys of my mostly happy childhood. Yet I know, too, that I will someday step in my own crack of time, and so I intend to fill the days between now and then with all the brand-new memories that they’ll hold. That’s what I’ve been trying to do ever since 9/11. So far it’s worked out pretty well.

* * *

John Gielgud speaks the “seven ages of man” monologue from Shakespeare’s As You Like It in a recording made in 1932:

A 1984 TV commercial for the Sears Christmas catalogue:

Steely Dan performs “Everything Must Go,” by Walter Becker and Donald Fagen, in 2003: