Thirty-one years ago, I was a senior editor at a magazine in New York, stuck (if that’s the word) in a job that didn’t satisfy me and not sure what to do about it. One morning I got a call from a man I didn’t know who said he’d like to talk to me about becoming an editorial writer for the New York Daily News. I’d never considered that line of work, but experience had taught me never to turn down a job offer without meeting the person who was making it, so I agreed to have lunch with Michael Pakenham, the editorial-page editor of the Daily News. I went to work for him a few weeks later, and continued to do so for the next six years.

Michael, who died yesterday at the age of eighty-five, was the last of my journalistic mentors, the older men who went out of their way to show me the ropes. He was, as they say, a character, a newspaperman who had started out as a reporter at the Chicago Tribune and was old enough to have put in a stretch at Chicago’s City News Bureau, where The Front Page is set. Not surprisingly, he loved to tell stories about the long-lost world of scoop-snatching beat reporting, about which he knew far more than most.

Michael, who died yesterday at the age of eighty-five, was the last of my journalistic mentors, the older men who went out of their way to show me the ropes. He was, as they say, a character, a newspaperman who had started out as a reporter at the Chicago Tribune and was old enough to have put in a stretch at Chicago’s City News Bureau, where The Front Page is set. Not surprisingly, he loved to tell stories about the long-lost world of scoop-snatching beat reporting, about which he knew far more than most.

From the Tribune, he moved to the New York Herald Tribune, the Philadelphia Inquirer, and the Daily News, switching along the way from reporting to editing and, eventually, to putting out editorial pages for major metropolitan dailies. He believed devoutly that newspaper editorials make a difference, instructing everyone who worked for him to try to write pieces that housewives from Queens would clip out of the paper and post on the doors of their refrigerators. He hired me in part because he preferred working with men and women of broad culture who weren’t set in their journalistic ways, having figured out that it was easier to teach a novice how to write effective editorials than to un-teach a tired old wheelhorse who’d written too many ineffective ones.

Michael’s own culture was unusually broad. He was widely and proudly read, and knew almost as much about classical music as he did about literature. It was at his urging and in his company that I first saw what is now my favorite painting. No sooner did I go to work for the News than we became friends, in part because we shared so many interests but mostly because I found him impossible not to like. He treated me as a trusted protégé and, like the ideal patron he was, spread the word about my talents. Among countless other beneficences, he introduced me to Rebecca Sinkler, then the editor of the New York Times Book Review, for which I started writing in 1990, a coup that did much to set me up in the world of literary journalism.

Michael’s editorial page was my finishing school. He taught me how to write short, fast, and with the kind of crisp immediacy you don’t learn from reviewing the Kansas City Philharmonic. He insisted that everyone who worked for him do everything there was to be done, from knocking out two-inch quickies about the school board to putting together the daily letters-to-the-editor column, and I learned as much from rotating through my varied tasks as I did from watching him blue-pencil my copy. On one never-to-be-forgotten occasion, he actually sent me to Albany to cover the release of New York’s state budget, about which I knew only slightly more than nothing, and made damned sure I got my facts straight. Nor will I soon forget the weekend when he called me at home and said, “The Berlin Wall has fallen. Get in your car and drive into town—we’ve got to redo the editorial page right now.” So we did, with wonder and awe.

Michael’s editorial page was my finishing school. He taught me how to write short, fast, and with the kind of crisp immediacy you don’t learn from reviewing the Kansas City Philharmonic. He insisted that everyone who worked for him do everything there was to be done, from knocking out two-inch quickies about the school board to putting together the daily letters-to-the-editor column, and I learned as much from rotating through my varied tasks as I did from watching him blue-pencil my copy. On one never-to-be-forgotten occasion, he actually sent me to Albany to cover the release of New York’s state budget, about which I knew only slightly more than nothing, and made damned sure I got my facts straight. Nor will I soon forget the weekend when he called me at home and said, “The Berlin Wall has fallen. Get in your car and drive into town—we’ve got to redo the editorial page right now.” So we did, with wonder and awe.

An immensely genial bon vivant, Michael was a superior cook and a comprehensively informed wine connoisseur. He claimed to have known everyone, or at least to have met them, and I was dazzled by his breadth of acquaintance. It was Bill Buckley who first told him about me, and his English relations included Lady Antonia Fraser and Lord Longford, his famously eccentric uncle. I knew him long enough to have heard the whole of his vast repertory of stories about the great and near-great, which glittered like a well-trimmed Christmas tree. On occasion I suspected him of anecdotal embroidery, especially when he had a sufficiency of Jameson under his belt: he swore, for example, that he had been in the room when Tallulah Bankhead, having just read Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, said to the rising young novelist, “So you’re the young man who doesn’t know how to spell fuck.” But he told his tales with such relish that I never had the heart to cross-examine him, and it wouldn’t have mattered in any case, for what he really did in the course of his forty-year career was so impressive that it needed no inflation.

It was dismayingly hard for Michael to find his footing when he left the Daily News. He was the first successful man I knew who had to struggle to jump-start his career in middle age, and it hurt me to watch him do it. I encouraged him to take time off and try his hand at writing a memoir, but his gifts didn’t run that way, and I wondered for a time whether he would ever right himself. Then, in 1995, he landed a new job as book-review editor of the Baltimore Sun, where I delighted in writing for him until he retired a decade later.

Michael spent his old age living in a country house in Pennsylvania that was too far from the beaten path to allow for easy commuting. My duties as a New York drama critic had become so all-consuming that it was all but impossible for me to visit him there, and our meetings, alas, became vanishingly rare, though he made the long trip into New York to give a toast at my wedding to Mrs. T. By then he had fallen in love and settled down with Rosalie, his beloved wife, who survives him. She will have no shortage of indelible memories to comfort her. Neither will I.

Michael spent his old age living in a country house in Pennsylvania that was too far from the beaten path to allow for easy commuting. My duties as a New York drama critic had become so all-consuming that it was all but impossible for me to visit him there, and our meetings, alas, became vanishingly rare, though he made the long trip into New York to give a toast at my wedding to Mrs. T. By then he had fallen in love and settled down with Rosalie, his beloved wife, who survives him. She will have no shortage of indelible memories to comfort her. Neither will I.

No one did more than Michael Pakenham to shape my career, or to make me the writer I am today. I have tried my best to do for others what he did for me. I bless his name.

* * *

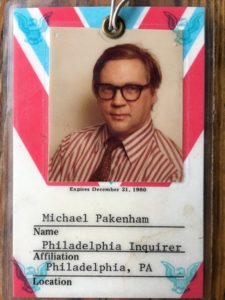

UPDATE: Michael’s Philadelphia Inquirer obituary is here.

Michael talks about Frank Rizzo, the Philadelphia mayor whom he covered during his tenure at the Philadelphia Inquirer: