I’ve been so preoccupied with the demands of my day job of late that I’m only just getting around to announcing the arrival of the latest addition to the Teachout Museum, a pencil-signed 1992 lithograph of Duke Ellington drawn by Al Hirschfeld.

I’ve been so preoccupied with the demands of my day job of late that I’m only just getting around to announcing the arrival of the latest addition to the Teachout Museum, a pencil-signed 1992 lithograph of Duke Ellington drawn by Al Hirschfeld.

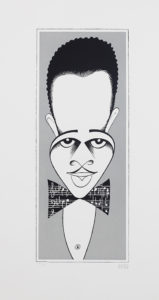

I am, needless to say, a great admirer of Hirschfeld, whose 1990 lithograph of Louis Armstrong has been on display in our New York apartment ever since Mrs. T and I bought it in 2014, a month after Satchmo at the Waldorf opened off Broadway. Just as I made a special point of reproducing “Satchmo!” in Pops, my Armstrong biography, so can this caricature—or, rather, an earlier version of it, about which more in a moment—be found in Duke: A Life of Duke Ellington. It stands to reason, then, that I also hoped someday to acquire a copy of “Duke Ellington,” not merely for sentimental reasons but because I believe it to be an exceptionally choice example of Hirschfeld’s work, a portrait as elegant and sly as Ellington himself.

Thereby hangs a tale, one that I told rather too briefly in Duke. It seems that Hirschfeld’s original caricature of Ellington, which now belongs to the National Portrait Gallery and on which he based this lithograph, was itself a new version of a much older drawing now known only to Ellington scholars, one that he had made in 1931 at the behest of Irving Mills, his manager.

As I explained in Duke:

Mills commissioned the jazz-loving theatrical cartoonist to draw a sketch that could be published by newspapers whose editors were unwilling to run photos of a black person—even one who, like Ellington, was an international celebrity. This witty (and respectful) art-deco caricature was included in one of the advertising manuals sent out by the Mills office.

To read that manual today is—to put it very, very mildly—an eye-opening experience, especially if you’re too young to recall the days when racial segregation was taken for granted throughout much of America. The anonymous author carefully explains to potential promoters that the Ellington band is “an attraction which may be just a little different than those you have handled previously. You may encounter some difficulty in planting photographs in newspapers, for example….Little objection ever has been voiced by amusement editors or radio editors to the use of this caricature in their columns. Many of the greatest metropolitan dailies in the country have used it.” And Mills’ subterfuge worked like a charm: Hirschfeld’s drawing appeared in papers all over the country, the Deep South included.

To read that manual today is—to put it very, very mildly—an eye-opening experience, especially if you’re too young to recall the days when racial segregation was taken for granted throughout much of America. The anonymous author carefully explains to potential promoters that the Ellington band is “an attraction which may be just a little different than those you have handled previously. You may encounter some difficulty in planting photographs in newspapers, for example….Little objection ever has been voiced by amusement editors or radio editors to the use of this caricature in their columns. Many of the greatest metropolitan dailies in the country have used it.” And Mills’ subterfuge worked like a charm: Hirschfeld’s drawing appeared in papers all over the country, the Deep South included.

I have no trouble understanding why Hirschfeld chose to redraw his very first Ellington caricature six decades after the fact (the original by then having long since vanished) and turn it into a limited-edition lithograph. To be sure, his portraits of Ellington in middle and old age are both charming and characteristic, but this one, made right around the time that he was turning out such early masterpieces as “Creole Rhapsody,” “Mood Indigo,” and “Rockin’ in Rhythm,” is something more than that. It is, above all, a portrait of the artist as a young man, pensive and—at least to my biographer’s eye—guarded, a man who poured his innermost feelings into his music but otherwise preferred to keep them hidden from the world.

The Ellington of this caricature is the same one whose complex personality I endeavored to suggest in my biography. It pleases me greatly that so handsome and revealing a work of art will now hang in the room where I wrote most of Duke.

* * *

To read more about Al Hirschfeld’s 1931 and 1992 caricatures of Duke Ellington, go here.