It’s been quite a while since Mrs. T and I last paid a joint visit to a museum, but we felt we couldn’t afford to miss American Post-Impressionists: Maurice & Charles Prendergast, which is up through June 10 at the New Britain Museum of American Art. Maurice Prendergast, who died in 1924, is one of my favorite turn-of-the-century American artists, but nowadays his work is for the most part known only to specialists, and I’ve never had the opportunity to see more than one or two of his paintings at a time. This exhibition, drawn from the permanent collections of the NBMAA and the Prendergast Archive & Study Center at the Williams College Museum of Art, is by way of being a full-scale joint retrospective of the work of the Prendergast brothers—it contains a hundred-odd works of various kinds—and you’ll come away from it with a clear sense of Maurice’s exceptional quality. (Charles was a talented artist, but he wasn’t in his brother’s league.)

It’s been quite a while since Mrs. T and I last paid a joint visit to a museum, but we felt we couldn’t afford to miss American Post-Impressionists: Maurice & Charles Prendergast, which is up through June 10 at the New Britain Museum of American Art. Maurice Prendergast, who died in 1924, is one of my favorite turn-of-the-century American artists, but nowadays his work is for the most part known only to specialists, and I’ve never had the opportunity to see more than one or two of his paintings at a time. This exhibition, drawn from the permanent collections of the NBMAA and the Prendergast Archive & Study Center at the Williams College Museum of Art, is by way of being a full-scale joint retrospective of the work of the Prendergast brothers—it contains a hundred-odd works of various kinds—and you’ll come away from it with a clear sense of Maurice’s exceptional quality. (Charles was a talented artist, but he wasn’t in his brother’s league.)

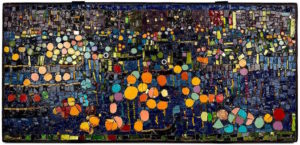

Mrs. T and I have similar but by no means identical tastes in art, so it surprised us that we singled out the same piece, an 1899 glass-and-ceramic-tiles mosaic called “Fiesta Grand Canal, Venice,” as our best-in-show pick. That said, “American Post-Impressionists: Maurice & Charles Prendergast” is full of striking work, and there’s nothing in it that isn’t worth seeing and pondering. Maurice was one of the first American painters to be strongly influenced by Cézanne, but his mature style was entirely original and immediately distinctive. He is also the only painter of importance I can think of who was deaf, and I can’t help but wonder whether that fact, and the resulting social isolation that his handicap imposed on him in his later years, had something to do with certain aspects of his style, among them his habit of painting vividly colored crowd scenes in which the individual figures are all faceless. Were they faceless because they were silent to him? I wonder.

Mrs. T and I have similar but by no means identical tastes in art, so it surprised us that we singled out the same piece, an 1899 glass-and-ceramic-tiles mosaic called “Fiesta Grand Canal, Venice,” as our best-in-show pick. That said, “American Post-Impressionists: Maurice & Charles Prendergast” is full of striking work, and there’s nothing in it that isn’t worth seeing and pondering. Maurice was one of the first American painters to be strongly influenced by Cézanne, but his mature style was entirely original and immediately distinctive. He is also the only painter of importance I can think of who was deaf, and I can’t help but wonder whether that fact, and the resulting social isolation that his handicap imposed on him in his later years, had something to do with certain aspects of his style, among them his habit of painting vividly colored crowd scenes in which the individual figures are all faceless. Were they faceless because they were silent to him? I wonder.

The NBMMA is a small, attractively housed Connecticut collection to which Mrs. T and I are both partial, and it would be worth visiting even if it weren’t hosting so fine a show. Small museums very often hang limited-edition prints of exceptionally high quality that are rarely on display in larger, better-stocked institutions, and we were tickled to discover that a handsome impression of one of our own pieces, a 1972 lithograph by Fairfield Porter called Broadway, was proudly hung in a first-floor gallery. Yale University Press was kind enough to allow me to reproduce Broadway on the dust jacket of A Terry Teachout Reader, and it pleased me no end to see it at the NBMMA. It was as if we’d unexpectedly bumped into an old friend in one of the galleries.

The NBMMA is a small, attractively housed Connecticut collection to which Mrs. T and I are both partial, and it would be worth visiting even if it weren’t hosting so fine a show. Small museums very often hang limited-edition prints of exceptionally high quality that are rarely on display in larger, better-stocked institutions, and we were tickled to discover that a handsome impression of one of our own pieces, a 1972 lithograph by Fairfield Porter called Broadway, was proudly hung in a first-floor gallery. Yale University Press was kind enough to allow me to reproduce Broadway on the dust jacket of A Terry Teachout Reader, and it pleased me no end to see it at the NBMMA. It was as if we’d unexpectedly bumped into an old friend in one of the galleries.

We were tickled in a different way when we arrived at the museum and discovered that having attained the august age of sixty-two, both of us now qualify for the NBMMA’s senior discount. Needless to say, I don’t think of myself as a senior citizen—I rarely feel much older than fifty or so, and most people seem to think I’m quite a bit younger than I look at first glance—and it had never before occurred to me that the time had finally come when I could get two dollars knocked off the price of admission to an art museum. So here it is at last, the distinguished thing, I muttered to myself as I stepped up to the front desk and confessed to being…well, middle-aged.

That same night I ran across the following passage in LaBrava, my favorite Elmore Leonard novel, in which a young photographer and an even younger beauty-product saleswoman are speculating on the age of a retired film-noir movie star whom they have just met:

That same night I ran across the following passage in LaBrava, my favorite Elmore Leonard novel, in which a young photographer and an even younger beauty-product saleswoman are speculating on the age of a retired film-noir movie star whom they have just met:

“How old you think she is?”

Franny said, “Well, let’s see. She looks pretty good for her age. I’d say she’s fifty-two.”

“You think she looks that old?”

“You asked me how old I think she is, not how old I think she looks.”

If you think that exchange pulled a deep sigh out of me, you’re right.

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.