A friend of mine has just discovered the music of Chet Baker, about whom I wrote sixteen years ago in The Wall Street Journal. Since that piece, a review of James Gavin’s Deep in a Dream: The Long Night of Chet Baker, has never been reprinted and is not available on line, I decided to post a lengthy excerpt for her benefit, as well as that of anyone else who’d like to know something about Baker’s pitiful life and beautiful art.

* * *

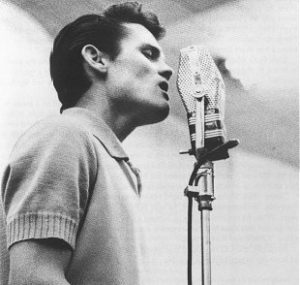

Anyone romantic enough to suppose that beauty is ennobling should spend an hour or two leafing through “Deep in a Dream,” James Gavin’s eagerly awaited biography of the jazz trumpeter Chet Baker. From time to time, musicians with a twisted sense of humor have been known to play the macabre game of choosing an all-star band comprised solely of players who are notorious for their compulsively self-destructive behavior; invariably, they pick Baker as solo trumpet. According to Mr. Gavin, he was mad, bad and dangerous to know—yet he played and sang ballads like “My Funny Valentine” and “She Was Too Good to Me” with a fragile tenderness and delicacy that could wring tears from the toughest of cynics.

Anyone romantic enough to suppose that beauty is ennobling should spend an hour or two leafing through “Deep in a Dream,” James Gavin’s eagerly awaited biography of the jazz trumpeter Chet Baker. From time to time, musicians with a twisted sense of humor have been known to play the macabre game of choosing an all-star band comprised solely of players who are notorious for their compulsively self-destructive behavior; invariably, they pick Baker as solo trumpet. According to Mr. Gavin, he was mad, bad and dangerous to know—yet he played and sang ballads like “My Funny Valentine” and “She Was Too Good to Me” with a fragile tenderness and delicacy that could wring tears from the toughest of cynics.

When not actually making music, Baker spent most of his adult life either getting high (he favored the lethal mixture of heroin and cocaine known as a speedball) or scrounging drug money from friends, lovers, colleagues and relatives. “All the attempts through the years to get him off heroin—he didn’t want to get off heroin,” said the baritone saxophonist Gerry Mulligan, in whose celebrated quartet Baker first won fame a half-century ago. Nobody knows for certain whether he fell, jumped or was pushed out of an Amsterdam hotel window in 1988, though it is widely thought that an unpaid dope dealer did him in. Similarly, many musicians believe that the person or persons unknown who attacked Baker in San Francisco in 1966, smashing his mouth so badly that his upper teeth had to be pulled and replaced with dentures, were paying him back for much the same reason.

In addition to being a dishonest wastrel, Baker was, as Mr. Gavin suggests, a kind of idiot savant, unable to read even the simplest of chord changes—he did it all by ear—and uninterested in learning anything about music beyond the basic knowledge needed to improvise technically undemanding trumpet solos with a minimum of high notes. “Maybe this rule stuff is all right for those who have no ear or creative ability,” he once told an interviewer. (So much for Louis Armstrong, who could both read and write music, just like the overwhelming majority of great jazz musicians.) Yet at his not-infrequent best, Baker could play jazz that was both piercingly beautiful and in no way aesthetically naïve. And while his whispery singing was more controversial, inspiring praise and contempt in equal measure, many listeners, this one included, find his tiny, feather-light tenor voice to be almost unbearably poignant.

A half-educated hick from Oklahoma, Baker was all but incapable of introspection, and rarely had anything insightful to say about his work. Nor is Mr. Gavin a trained musician, meaning that he can shed no analytic light on Baker’s playing. Of necessity, then, “Deep in a Dream” deals primarily with his sordid life. Unlike most musical biographies written by non-musicians, however, this one works—partly because that life was so appallingly eventful, but mostly because Mr. Gavin has done his job with scrupulous care, separating fact from rumor and facing up to the full implications of Baker’s despicable conduct. Unlike Bruce Weber, the fashion photographer turned filmmaker whose 1989 documentary “Let’s Get Lost” treated the handsome trumpeter as a glamorously decadent object of desire, James Gavin has no illusions about Chet Baker. Though he understands the perverse appeal of “the beautiful, self-destructive rebel who lived on the run, avoiding responsibility, rejecting convention,” he treats Baker not as a pretty pin-up boy but as a serious artist worthy of intelligent consideration….

A half-educated hick from Oklahoma, Baker was all but incapable of introspection, and rarely had anything insightful to say about his work. Nor is Mr. Gavin a trained musician, meaning that he can shed no analytic light on Baker’s playing. Of necessity, then, “Deep in a Dream” deals primarily with his sordid life. Unlike most musical biographies written by non-musicians, however, this one works—partly because that life was so appallingly eventful, but mostly because Mr. Gavin has done his job with scrupulous care, separating fact from rumor and facing up to the full implications of Baker’s despicable conduct. Unlike Bruce Weber, the fashion photographer turned filmmaker whose 1989 documentary “Let’s Get Lost” treated the handsome trumpeter as a glamorously decadent object of desire, James Gavin has no illusions about Chet Baker. Though he understands the perverse appeal of “the beautiful, self-destructive rebel who lived on the run, avoiding responsibility, rejecting convention,” he treats Baker not as a pretty pin-up boy but as a serious artist worthy of intelligent consideration….

The problem is that Baker’s life, though interesting, wasn’t exactly edifying. He played music, shot dope and slept with foolish women, and that’s about the size of it. Reading about him is like watching a ten-car pile-up on an ice-covered road: it’s sickening, but you can’t turn away. In Baker’s case, you keep trying to guess just how low he can possibly sink, and he keeps surprising you. It wasn’t until the last day of his life that he finally hit bottom, cracking open his skull and bringing to a long-deferred close a career that by all rights should have ended years before.

James Gavin tells us everything we could possibly want to know about Baker, save for the one unknowable thing that matters most. Where did all that beauty come from? It is the highest possible tribute to Chet Baker’s haunted art that after reading “Deep in a Dream,” we should still wonder.

* * *

Chet Baker performs “My Funny Valentine” on TV in 1959:

Chet Baker performs “Love for Sale” in concert in 1979: