In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” columns I pay tribute to one of the most interesting magazines of the Thirties. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Of all the American general-interest magazines that came and (mostly) went in the 20th century, surely the most enduringly significant is the New Yorker, launched by Harold Ross in 1925 and published to this day in a format that would be easily recognizable to its charter subscribers. Only Reader’s Digest and Time have had longer runs, and both are now well past the peak of their once-formidable influence. Not so the New Yorker, which is as central to the cultural conversation today as it was when Ross and William Shawn, his successor, called its editorial tune.

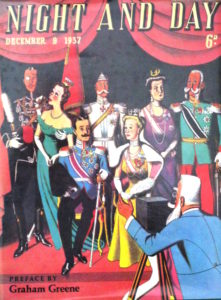

The New Yorker has been around so long that it is surprising how few imitators it has spawned. Moreover, none of them were commercially successful, and only one is still known, if only to literary connoisseurs: Night and Day, a weekly that sought to transplant the sophisticated style and design of the New Yorker to England between the wars. While it was published for only a short time, putting out its inaugural issue in July of 1937 and shutting down six months later, Night and Day made a impression that has yet to fade. It pops up, for instance, in “Dancing to the Music of Time,” Hilary Spurling’s new biography of the novelist Anthony Powell, a regular contributor to Night and Day, who had previously recalled its “undoubted freshness and style” in “To Keep the Ball Rolling,” his 1983 memoir.

The New Yorker has been around so long that it is surprising how few imitators it has spawned. Moreover, none of them were commercially successful, and only one is still known, if only to literary connoisseurs: Night and Day, a weekly that sought to transplant the sophisticated style and design of the New Yorker to England between the wars. While it was published for only a short time, putting out its inaugural issue in July of 1937 and shutting down six months later, Night and Day made a impression that has yet to fade. It pops up, for instance, in “Dancing to the Music of Time,” Hilary Spurling’s new biography of the novelist Anthony Powell, a regular contributor to Night and Day, who had previously recalled its “undoubted freshness and style” in “To Keep the Ball Rolling,” his 1983 memoir.

Two years after that, Christopher Hawtree published a lively coffee-table anthology called “Night and Day” whose star-studded index shows why the magazine is so well remembered. (The book is out of print, but used copies are fairly easy to find.) In addition to Powell, the regular contributors included, among others, Evelyn Waugh, who reviewed books; Graham Greene, the co-editor, who doubled as film critic; and John Betjeman, Elizabeth Bowen, Alistair Cooke, Christopher Isherwood, Constant Lambert, Malcolm Muggeridge and Herbert Read. All were mainly out to amuse, though Night and Day was not above publishing more serious fare. For the most part, however, it was, like the New Yorker in the ’20s and ’30s, a chiefly comic magazine. Therein lay its appeal: At a time when England was looking nervously at the totalitarian monsters who were swallowing up Europe, Night and Day gave its subscribers something to smile about….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.