Fred Hersch plays Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” at Lincoln Center in 2016:

Fred Hersch plays Joni Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now” at Lincoln Center in 2016:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“I understood why these guys bowed before Peterson—his technique was indisputably impressive, and he was a dazzling player, if a bit stiff. But even then, when my ears were still developing, I wasn’t much impressed by impressiveness.”

“I understood why these guys bowed before Peterson—his technique was indisputably impressive, and he was a dazzling player, if a bit stiff. But even then, when my ears were still developing, I wasn’t much impressed by impressiveness.”

Fred Hersch, Good Things Happen Slowly: A Life In and Out of Jazz

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I report on an extremely rare revival by the Mint Theater Company of Stanley Houghton’s Hindle Wakes. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Of all the countless off-Broadway troupes with which the side streets of Manhattan are dotted, none has a more distinctive mission—or a higher artistic batting average—than the Mint Theater Company, which “finds and produces worthwhile plays from the past that have been lost or forgotten.” If that sounds dull to you, don’t be fooled: I’ve never seen a production there that was a sliver less than superb. Rachel Crothers’ “Susan and God,” John Galsworthy’s “The Skin Game,” Harley Granville-Barker’s “The Madras House,” N.C. Hunter’s “A Day by the Sea,” Dawn Powell’s “Walking Down Broadway,” Jules Romain’s “Doctor Knock,” John Van Druten’s “London Wall”: All these fine plays and others just as good have been exhumed by the Mint to memorable effect in the 13 years that I’ve been reviewing the company, a tribute to the uncanny taste and unfailing resourcefulness of Jonathan Bank, the artistic director.

This time around, though, Mr. Bank has really pulled one out of his seemingly bottomless hat. I’d never even heard the name of Stanley Houghton, an English playwright who died in 1913 at the age of 32, before the Mint announced its latest revival, a Houghton play called “Hindle Wakes” that hasn’t been staged in the U.S. since 1922. Were it being produced by any other company in New York, I’d probably have passed on so obscure an offering, but the Mint’s infallible record of success led me to roll the dice. It was the right call, too: Not only was Houghton an artist of exceptional skill, but “Hindle Wakes,” his last play, is a study of provincial hypocrisy in Vicwardian England that crackles with a biting candor fully worthy of George Bernard Shaw, on whose far better-known plays it was plainly modeled.

This time around, though, Mr. Bank has really pulled one out of his seemingly bottomless hat. I’d never even heard the name of Stanley Houghton, an English playwright who died in 1913 at the age of 32, before the Mint announced its latest revival, a Houghton play called “Hindle Wakes” that hasn’t been staged in the U.S. since 1922. Were it being produced by any other company in New York, I’d probably have passed on so obscure an offering, but the Mint’s infallible record of success led me to roll the dice. It was the right call, too: Not only was Houghton an artist of exceptional skill, but “Hindle Wakes,” his last play, is a study of provincial hypocrisy in Vicwardian England that crackles with a biting candor fully worthy of George Bernard Shaw, on whose far better-known plays it was plainly modeled.

Fanny Hawthorn (Rebecca Noelle Brinkley), the sparky Lancashire lass at the center of “Hindle Wakes,” lives with her working-class parents (Ken Marks and Sandra Shipley) and toils alongside Christopher, her father, in Hindle’s cotton mill. She’s returned home much later than expected from what the Brits used to call a “dirty weekend” with Alan Jeffcote (Jeremy Beck), a hard-drinking young man about town. No sooner do the Hawthorns confront Fanny, demanding that she tell them where she went and what she did there, than Christopher pays an unscheduled call on Alan’s father Nathaniel (Jonathan Hogan), the owner of the mill and the richest man in town. The objective, naturally, is to force Alan to make an honest woman out of Fanny, but that’s where the plot starts to thicken. Nathaniel, it seems, is a childhood friend of Christopher who clawed his way up the greasy pole of success. What’s more, he’s about to marry off his ne’er-do-well son to Beatrice (Emma Geer), the mayor’s daughter, thereby securing for himself and his wife (Jill Tanner) a place in society that the money of a self-made businessman who “started life in a weaving shed” can’t buy.

What we have here, in short, is a standard-issue clockwork melodrama—except that “Hindle Wakes” proves to be nothing of the kind. The difference is that save for Fanny’s earnest, hapless father, all of the characters respond to her dilemma in unexpected ways, none more so than Nathaniel, a coolly sardonic businessman in the Trollopian mold…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” columns I pay tribute to one of the most interesting magazines of the Thirties. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Of all the American general-interest magazines that came and (mostly) went in the 20th century, surely the most enduringly significant is the New Yorker, launched by Harold Ross in 1925 and published to this day in a format that would be easily recognizable to its charter subscribers. Only Reader’s Digest and Time have had longer runs, and both are now well past the peak of their once-formidable influence. Not so the New Yorker, which is as central to the cultural conversation today as it was when Ross and William Shawn, his successor, called its editorial tune.

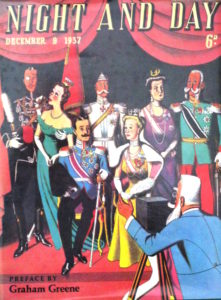

The New Yorker has been around so long that it is surprising how few imitators it has spawned. Moreover, none of them were commercially successful, and only one is still known, if only to literary connoisseurs: Night and Day, a weekly that sought to transplant the sophisticated style and design of the New Yorker to England between the wars. While it was published for only a short time, putting out its inaugural issue in July of 1937 and shutting down six months later, Night and Day made a impression that has yet to fade. It pops up, for instance, in “Dancing to the Music of Time,” Hilary Spurling’s new biography of the novelist Anthony Powell, a regular contributor to Night and Day, who had previously recalled its “undoubted freshness and style” in “To Keep the Ball Rolling,” his 1983 memoir.

The New Yorker has been around so long that it is surprising how few imitators it has spawned. Moreover, none of them were commercially successful, and only one is still known, if only to literary connoisseurs: Night and Day, a weekly that sought to transplant the sophisticated style and design of the New Yorker to England between the wars. While it was published for only a short time, putting out its inaugural issue in July of 1937 and shutting down six months later, Night and Day made a impression that has yet to fade. It pops up, for instance, in “Dancing to the Music of Time,” Hilary Spurling’s new biography of the novelist Anthony Powell, a regular contributor to Night and Day, who had previously recalled its “undoubted freshness and style” in “To Keep the Ball Rolling,” his 1983 memoir.

Two years after that, Christopher Hawtree published a lively coffee-table anthology called “Night and Day” whose star-studded index shows why the magazine is so well remembered. (The book is out of print, but used copies are fairly easy to find.) In addition to Powell, the regular contributors included, among others, Evelyn Waugh, who reviewed books; Graham Greene, the co-editor, who doubled as film critic; and John Betjeman, Elizabeth Bowen, Alistair Cooke, Christopher Isherwood, Constant Lambert, Malcolm Muggeridge and Herbert Read. All were mainly out to amuse, though Night and Day was not above publishing more serious fare. For the most part, however, it was, like the New Yorker in the ’20s and ’30s, a chiefly comic magazine. Therein lay its appeal: At a time when England was looking nervously at the totalitarian monsters who were swallowing up Europe, Night and Day gave its subscribers something to smile about….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• The Band’s Visit (musical, PG-13, nearly all shows sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Dear Evan Hansen (musical, PG-13, all shows sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Hamilton (musical, PG-13, Broadway transfer of off-Broadway production, all shows sold out last week, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN WASHINGTON, D.C.:

• The Skin of Our Teeth (tragicomedy, G/PG-13, closes Feb. 18, reviewed here)

CLOSING SOON IN MALVERN, PA.:

• Morning’s at Seven (serious comedy, G/PG-13, extended through Feb. 11, reviewed here)

“People think because a novel’s invented, it isn’t true. Exactly the reverse is the case. Because a novel’s invented, it is true. Biography and memoirs can never be wholly true, since they can’t include every conceivable circumstance of what happened. The novel can do that. The novelist himself lays it down. His decision is binding.”

“People think because a novel’s invented, it isn’t true. Exactly the reverse is the case. Because a novel’s invented, it is true. Biography and memoirs can never be wholly true, since they can’t include every conceivable circumstance of what happened. The novel can do that. The novelist himself lays it down. His decision is binding.”

Anthony Powell, Hearing Secret Harmonies

An ArtsJournal Blog