“I am no great believer in compromises: someone always gets hurt, deeper than in a clean cut.”

“I am no great believer in compromises: someone always gets hurt, deeper than in a clean cut.”

Michael Powell, A Life in Movies: An Autobiography

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

In 1961 my parents moved into a new ranch house in Smalltown, U.S.A., where they lived until they died. David and Kathy, my brother and sister-in-law, live there now, and since my parents were packrats equipped with a big basement, my brother has of necessity become the family archivist. The job suits him, for he has an impeccable memory for trivia and, like me, isn’t even slightly alienated from the past that we share: he loved both of our parents deeply and is proud to have made them proud of him.

In 1961 my parents moved into a new ranch house in Smalltown, U.S.A., where they lived until they died. David and Kathy, my brother and sister-in-law, live there now, and since my parents were packrats equipped with a big basement, my brother has of necessity become the family archivist. The job suits him, for he has an impeccable memory for trivia and, like me, isn’t even slightly alienated from the past that we share: he loved both of our parents deeply and is proud to have made them proud of him.

From time to time, David sends me little gifts that have turned up in the course of his researches. A couple of weeks ago, for instance, Mrs. T and I returned from Philadelphia to find a box on our front porch that contained three family-related items. Two of them were tins full of Christmas cookies baked by my brother, half molasses and half sugar with red and green sprinkles, all cut with the very same cookie cutters that my mother got out of storage every December. I’m pretty sure he uses the same recipes, too. Each time I eat one of those cookies, I think of the wonderful family Christmases of my youth and smile.

The third item was a colorfully printed, handsomely framed certificate issued on February 12, 1946, by an entity known as “the Golden Dragon, Ruler of the 180th Meridian.” It reads as follows:

The third item was a colorfully printed, handsomely framed certificate issued on February 12, 1946, by an entity known as “the Golden Dragon, Ruler of the 180th Meridian.” It reads as follows:

To all Sailors, Soldiers, Marines, wherever ye may be and to all mermaids, flying dragons, spirits of the deep, devil chasers, and all other living creatures of the yellow seas, Greetings: Know ye that on the 12th day of Febuary 1946, in latitude 30 degrees N longitude 180 degrees W there appeared within the limits of my august dwelling the USS Admiral C.F. Hughes (AP-124).

Hearken Ye: The said vessel, officers and crew have been inspected and passed on by my august body and staff. And know ye: Ye that are chit signers, squaw men, opium smokers, ice men, and all-round landlubbers that Herbert H. Teachout, having been found sane and worthy to be numbered a dweller of the Far East has been gathered in my fold and duly initiated into the Silent Mysteries of the Far East.

Be it further understood: That by virtue of the power vested in me I do hereby command all money lenders, wine sellers, cabaret owners, cat-house managers and all my other subjects to show honor and respect to all his wishes whenever he may enter my realm. Disobey this command under penalty of my august displeasure.

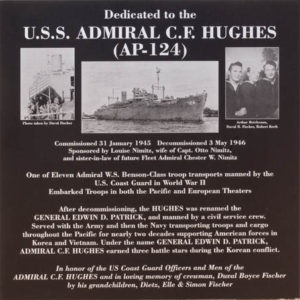

At first glance the certificate threw me for a loop. Then the light went on: my father must have been presented with it en route to the Philippines, where he served in World War II. So I turned to Wikipedia, where I learned that the Domain of the Golden Dragon is, as I guessed, an unofficial award that is still given by the U.S. Navy to the crew members of ships that cross the International Date Line. The Admiral C.F. Hughes, on which he sailed in 1946, was a troop transport built in 1944 that ferried American soldiers and sailors and Japanese prisoners of war to and from ports in the Pacific. The first transport to reach the West Coast after the Japanese surrender, It remained in use until 1967.

At first glance the certificate threw me for a loop. Then the light went on: my father must have been presented with it en route to the Philippines, where he served in World War II. So I turned to Wikipedia, where I learned that the Domain of the Golden Dragon is, as I guessed, an unofficial award that is still given by the U.S. Navy to the crew members of ships that cross the International Date Line. The Admiral C.F. Hughes, on which he sailed in 1946, was a troop transport built in 1944 that ferried American soldiers and sailors and Japanese prisoners of war to and from ports in the Pacific. The first transport to reach the West Coast after the Japanese surrender, It remained in use until 1967.

David found the certificate in the course of one of his basement excavations. It was part of a cache of wartime souvenirs, none of which my father ever bothered to show us, just as he never talked about his time in the Army Air Corps unless asked. Not that there would have been much to tell: drafted at the very end of 1944, he did his basic training at Keesler Field in Mississippi, where Neil Simon’s Biloxi Blues is set, but he never saw combat and didn’t make it to the Philippines until after V-J Day.

David found the certificate in the course of one of his basement excavations. It was part of a cache of wartime souvenirs, none of which my father ever bothered to show us, just as he never talked about his time in the Army Air Corps unless asked. Not that there would have been much to tell: drafted at the very end of 1944, he did his basic training at Keesler Field in Mississippi, where Neil Simon’s Biloxi Blues is set, but he never saw combat and didn’t make it to the Philippines until after V-J Day.

My father and I weren’t intimate enough for me to ask him awkward questions, so I never quizzed him about his Army days. The only thing he ever told me was that he and Veronica Lake had once shared a plane, a thought that makes me boggle even more now than it did then. After he died, though, my mother explained to my brother that he didn’t talk about the war because he was ashamed not to have been in combat. I have no trouble believing that. Thanks to Verona, his haughty mother, he grew up to be a strong but insecure man who never felt at ease in his own skin and was incapable of believing that he was both a good man and a good father. Small wonder, then, that his unspectacular wartime record gnawed at his pride.

Now that the Greatest Generation is vanishing from the scene in ever-increasing numbers, I find myself thinking more and more about my parents. Having been close to my mother, I’m not surprised that I miss her as much as I do. What surprises me is that I think so much about my father, whom I loved but with whom I could never quite get along. I wish with all my heart that I could have bridged the gap of temperament that separated us. I would give anything to sit down with him one more time and ask him about the war in which he served—and tell him how proud I was of his service, uneventful though it was.

Now that the Greatest Generation is vanishing from the scene in ever-increasing numbers, I find myself thinking more and more about my parents. Having been close to my mother, I’m not surprised that I miss her as much as I do. What surprises me is that I think so much about my father, whom I loved but with whom I could never quite get along. I wish with all my heart that I could have bridged the gap of temperament that separated us. I would give anything to sit down with him one more time and ask him about the war in which he served—and tell him how proud I was of his service, uneventful though it was.

As for the C.F. Hughes, it was broken up for scrap in 2011, and most of the men who sailed on it during World War II have gone, like my father, to their graves. All that remains of his old ship is a plaque on the wall of the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, Texas. It’s not far from Austin, and maybe I’ll go there one of these days.

If I do, I’ll look up the plaque that commemorates the nondescript life of my father’s ship, and hear in my mind’s ear the little speech that Willie Keith delivers at the end of The Caine Mutiny when he turns the U.S.S. Caine over for decommissioning:

If I do, I’ll look up the plaque that commemorates the nondescript life of my father’s ship, and hear in my mind’s ear the little speech that Willie Keith delivers at the end of The Caine Mutiny when he turns the U.S.S. Caine over for decommissioning:

It’s a broken-down obsolete ship. It steamed through four years of war. It has no unit citation and it achieved nothing spectacular. It was supposed to be a minesweeper, but in the whole war it swept six mines. It did every kind of menial fleet duty, mostly several hundred thousand miles of dull escorting. Now it’s a damaged hulk and will probably be broken up. Every hour spent on the Caine was a great hour in all our lives—if you don’t think so now you will later on, more and more. We were all doing part of what had to be done to keep our country existing, not any better than before, just the same old country that we love. We’re all landlubbers who pitted our lives and brains against the sea and the enemy, and did what we were told to do. The hours we spent on the Caine were hours of glory. They are all over. We’ll scatter into the trains and busses now and most of us will go home. But we will remember the Caine, the old ship in which we helped to win the war.

My father owned a copy of The Caine Mutiny. He wasn’t a reading man, but I wonder whether he made an exception for that novel, and if he thought of himself when he read those words. I know I do.

* * *

A scene from the film version of Biloxi Blues, directed by Mike Nichols and starring Matthew Broderick and Christopher Walken:

Unless you happen to own a newspaper, you don’t get to read your own obituary. And that’s probably as it should be. I’ve written some pretty sharp remarks about the recently deceased, after all, and I wouldn’t be surprised if somebody remembered them when my own time comes–or maybe not. Perhaps I’ll outlive my own minor renown and be remembered solely, as I once speculated in this space, for having owned a Max Beerbohm caricature. Would I want to know that now? Not really. I have a pretty good sense of irony, but I’m not sure it’s that robust….

Read the whole thing here.

Otto Klemperer leads Agnes Giebel, Marga Hoffgen, Ernst Haefliger, Gustav Neidlinger, and the New Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra in a live performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. This performance was taped in London’s Royal Albert Hall in 1964:

Otto Klemperer leads Agnes Giebel, Marga Hoffgen, Ernst Haefliger, Gustav Neidlinger, and the New Philharmonia Chorus and Orchestra in a live performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony. This performance was taped in London’s Royal Albert Hall in 1964:

(This is the latest in a series of arts- and history-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“We talk, by a sort of habit, about Modern Thought, forgetting the familiar fact that moderns do not think. They only feel, and that is why they are so much stronger in fiction than in facts; why their novels are so much better than their newspapers.”

“We talk, by a sort of habit, about Modern Thought, forgetting the familiar fact that moderns do not think. They only feel, and that is why they are so much stronger in fiction than in facts; why their novels are so much better than their newspapers.”

G.K. Chesterton, “The Trouble With Our Pagans” (Illustrated London News, Sept. 13, 1930)

Mrs. T and I went to Florida for the first time in January of 2009. It was the first leg of a marathon reviewing trip that subsequently took us to San Francisco, San Diego, Kansas City, Chicago, and Lenox, Massachusetts. Going south to see shows was nothing more than an experiment, and I was astonished to discover that Florida, notwithstanding its reputation as a paradise for lowbrows, was in fact full of first-rate drama companies. January is a famously slow month for theater in New York, so we returned the following year to find out whether the quality of the shows that we’d seen in 2009 had been a fluke. It wasn’t, and we’ve been going back ever since.

Mrs. T and I went to Florida for the first time in January of 2009. It was the first leg of a marathon reviewing trip that subsequently took us to San Francisco, San Diego, Kansas City, Chicago, and Lenox, Massachusetts. Going south to see shows was nothing more than an experiment, and I was astonished to discover that Florida, notwithstanding its reputation as a paradise for lowbrows, was in fact full of first-rate drama companies. January is a famously slow month for theater in New York, so we returned the following year to find out whether the quality of the shows that we’d seen in 2009 had been a fluke. It wasn’t, and we’ve been going back ever since.

At some point along the way, it hit the two of us that we’d turned willy-nilly into part-time snowbirds, fleeing to Florida after Christmas to escape the brutal cold of New York and Connecticut. Needless to say, we wouldn’t have kept on doing so it not been for the high quality of the shows that we saw there, but as Mrs. T’s chronic illness gnawed away at her stamina, the (mostly) benign weather in south Florida proved to be a coincidental blessing. Instead of hiding indoors from the deadly chill, she walked on the beach every day. We fell in love with seaside life, taking boat rides to nowhere and going out to see movies instead of staying home to watch them on TV. Most nights we sat on the porch and watched the sun set over the Gulf of Mexico, asking ourselves what we’d done to be so lucky.

At some point along the way, it hit the two of us that we’d turned willy-nilly into part-time snowbirds, fleeing to Florida after Christmas to escape the brutal cold of New York and Connecticut. Needless to say, we wouldn’t have kept on doing so it not been for the high quality of the shows that we saw there, but as Mrs. T’s chronic illness gnawed away at her stamina, the (mostly) benign weather in south Florida proved to be a coincidental blessing. Instead of hiding indoors from the deadly chill, she walked on the beach every day. We fell in love with seaside life, taking boat rides to nowhere and going out to see movies instead of staying home to watch them on TV. Most nights we sat on the porch and watched the sun set over the Gulf of Mexico, asking ourselves what we’d done to be so lucky.

It wasn’t too good to be true, but it was too good to last. Both of us had a feeling that we might not be coming back to Florida this January, and sure enough, the doctors told us a couple of months ago that the time had come at last for Mrs. T to hang up her traveling shoes and start waiting for the Big Call.

This is, lest any of you forget, very good news. It means that she will eventually be summoned either to New York-Presbyterian Hospital or Philadelphia’s Penn Transplant Institute, where she’ll receive a used pair of lungs and—if the fates allow—a new lease on life. Nevertheless, we’re going to be watching the winter of 2018 up close instead of from the comfortable vantage point of Sanibel Island. As I write these words, it’s one degree above zero in northeast Connecticut. Our front lawn is covered with snow and the sun set not at 5:45 but 4:27. We’re no longer accustomed to any of these things, and we don’t like them one little bit. It’s funny how fast you can get used to the stupendous luxury of not having to put up with grimy snow and slate-gray skies—and how easily you can forget the toll such ceaseless bleakness takes on the human spirit.

This is, lest any of you forget, very good news. It means that she will eventually be summoned either to New York-Presbyterian Hospital or Philadelphia’s Penn Transplant Institute, where she’ll receive a used pair of lungs and—if the fates allow—a new lease on life. Nevertheless, we’re going to be watching the winter of 2018 up close instead of from the comfortable vantage point of Sanibel Island. As I write these words, it’s one degree above zero in northeast Connecticut. Our front lawn is covered with snow and the sun set not at 5:45 but 4:27. We’re no longer accustomed to any of these things, and we don’t like them one little bit. It’s funny how fast you can get used to the stupendous luxury of not having to put up with grimy snow and slate-gray skies—and how easily you can forget the toll such ceaseless bleakness takes on the human spirit.

Some, I hear tell, like it cold, but the older I get, the surer I am that I don’t fit in that pigeonhole. To be sure, I used to think I was a cold-weather person, but in late middle age I find that I strongly favor early autumn, the gentle, comforting season of gorgeous foliage and fresh corn and tomatoes. No, the palm trees on Sanibel Island don’t turn red and gold in January, but the weather outside is deliciously satisfying, as are the ever-renewing, ever-refreshing sight and sound of the sea.

Be that as it may, Mrs. T and I are doing our damnedest to fly the flag of good cheer. We bundled up and went to see Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri over the weekend, and in lieu of flying to Florida, we’ll hop in the car later today and depart on a week-long holiday stay at two of our favorite retreats. From then on, though, we’ll both be sticking close to home.

Covering regional theater has been a big part of my professional life throughout the past decade, and it feels odd to think that I won’t be cooling my heels in airports until further notice. On the other hand, New York and its immediate environs offer no shortage of shows to see, so I expect to keep busy. I suppose, too, that I’ll be embarking on some sort of new writing project now that Billy and Me is properly launched. Right now, though, I don’t feel like firing up my creative engines just yet. I need to wind down from my recent adventures in West Palm Beach, and—more important—I mean to spend all the time that I possibly can looking after my beloved Mrs. T.

Covering regional theater has been a big part of my professional life throughout the past decade, and it feels odd to think that I won’t be cooling my heels in airports until further notice. On the other hand, New York and its immediate environs offer no shortage of shows to see, so I expect to keep busy. I suppose, too, that I’ll be embarking on some sort of new writing project now that Billy and Me is properly launched. Right now, though, I don’t feel like firing up my creative engines just yet. I need to wind down from my recent adventures in West Palm Beach, and—more important—I mean to spend all the time that I possibly can looking after my beloved Mrs. T.

All of which brings us to the arrival of 2018, on whose first day the two of us are simultaneously frightened and full of hope. Both of these things being the case, allow me to post, as is my custom, the Ogden Nash poem that I like to share with you on this date, followed by my customary end-of-the-year good wishes:

All of which brings us to the arrival of 2018, on whose first day the two of us are simultaneously frightened and full of hope. Both of these things being the case, allow me to post, as is my custom, the Ogden Nash poem that I like to share with you on this date, followed by my customary end-of-the-year good wishes:

Come, children, gather round my knee;

Something is about to be.

Tonight’s December Thirty-First,

Something is about to burst.

The clock is crouching, dark and small,

Like a time bomb in the hall.

Hark! It’s midnight, children dear.

Duck! Here comes another year.

To all of you who, like me, suspect that chance is in the saddle and rides mankind, I hope that the year to come treats you not unkindly, and that your lives, like mine, will be warmed by hope and filled with love.

* * *

The Choir of King’s College, Cambridge, sings Gustav Holst’s setting of Christina Rossetti’s “In the Bleak Midwinter”:

An ArtsJournal Blog