“We begin to live when we have conceived life as tragedy.”

“We begin to live when we have conceived life as tragedy.”

W.B. Yeats, The Trembling of the Veil

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

Seeking to rest my weary mind, I brought a short stack of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe mystery novels with me to Upper Black Eddy, Pennsylvania, where Mrs. T and I retreated last week from the encroaching world. One of them is a tattered mass-market paperback edition of Murder by the Book, originally published in 1951. I bought it for thirty-nine cents at the Book Bug, the long-defunct used bookstore in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, where I spent much of my allowance back in the days when my parents gave me an allowance. I know all this because the inside of my copy of Murder by the Book is rubber-stamped to that effect, and further inspection reveals that this particular edition was published in October of 1970. It’s quite possible, then, that I’ve owned it longer than any other book in my personal library.

Seeking to rest my weary mind, I brought a short stack of Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe mystery novels with me to Upper Black Eddy, Pennsylvania, where Mrs. T and I retreated last week from the encroaching world. One of them is a tattered mass-market paperback edition of Murder by the Book, originally published in 1951. I bought it for thirty-nine cents at the Book Bug, the long-defunct used bookstore in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, where I spent much of my allowance back in the days when my parents gave me an allowance. I know all this because the inside of my copy of Murder by the Book is rubber-stamped to that effect, and further inspection reveals that this particular edition was published in October of 1970. It’s quite possible, then, that I’ve owned it longer than any other book in my personal library.

Needless to say, Rex Stout and I go back a long way. In 2009 I posted at length about my long-term love affair with his Nero Wolfe novels, though that wasn’t the first time I wrote about them. Seven years earlier I’d reviewed A&E’s A Nero Wolfe Mystery, a TV series based on the books that had a two-season run on A&E. I put a lot of work into that forgotten essay, which originally appeared in National Review and has never been reprinted, and so I was delighted to find it on line the other day. I post it here for your amusement and edification.

* * *

Some cable networks are destinations, others way stations. Arts & Entertainment has long been one of the latter, a vaguely defined middlebrow enterprise across which one occasionally stumbles while channel-surfing. I’ve seen Biography, its best-known series, a couple of dozen times, but never deliberately—only in passing, usually when I’m killing time in a hotel room and can’t find anything better to watch. Hence it is with no small amount of surprise that I now find myself tuning in A&E every Sunday night to keep up with the doings of a monstrously fat private detective who swills beer by the case, fusses over his thrice-daily gourmet meals, dresses in sunflower-yellow shirts, and grows orchids in a greenhouse on the roof of his Manhattan brownstone, whose threshold he crosses only when compelled by the threat of impending arrest.

Older readers will need no further introduction to Nero Wolfe, the larger-than-life hero of seventy-three novels and novellas written by Rex Stout between 1934 and his death in 1975. For most of his long life, Stout was acclaimed as one of America’s best mystery writers—even Edmund Wilson, who despised the genre, grudgingly admitted that he “rather enjoyed” Wolfe—and though his star has faded a bit in recent years, paperback editions of his books are still kept in print on a rotating basis by Bantam.

Older readers will need no further introduction to Nero Wolfe, the larger-than-life hero of seventy-three novels and novellas written by Rex Stout between 1934 and his death in 1975. For most of his long life, Stout was acclaimed as one of America’s best mystery writers—even Edmund Wilson, who despised the genre, grudgingly admitted that he “rather enjoyed” Wolfe—and though his star has faded a bit in recent years, paperback editions of his books are still kept in print on a rotating basis by Bantam.

A half-dozen prior attempts have been made to bring Wolfe to TV, radio, and the movies, and all have failed dismally. Not so A&E’s Nero Wolfe. It isn’t perfect, but it comes close, in part for the simplest of reasons: Timothy Hutton and Michael Jaffe, the executive producers, have chosen to stick as closely as possible to the source. Each episode is based on a Stout story (the novels are done as two-parters, the novellas in single hour-long episodes). The plots are left intact, and large chunks of dialogue are lifted straight off the page. If you’ve read Death of a Doxy, Too Many Clients, or The Mother Hunt, you won’t find anything surprising about the A&E versions.

To be sure, faithfulness to the original is no guarantee of success when translating a familiar novel to the screen. More often than not, literal adaptations are redundant at best (why bother?), maladroit at worst. Novels aren’t meant to be played out in real time, and even when the action is scrupulously compressed, you still have to find actors and actresses capable of fitting the preconceptions of viewers who’ve already read the book. As a general rule, the better bet is to treat the source material as a point of departure—the way Amy Heckerling did when she turned Jane Austen’s Emma into Clueless—rather than following it slavishly, but that approach is impossible when the novel in question is a cult classic. Rex Stout fans want to know exactly what the brownstone on West 35th Street “really” looks like, though they expect it to bear a close resemblance to the one in their heads, just as they have the strongest possible opinions about what Nero Wolfe looks and sounds like, not to mention Archie Goodwin, his wisecracking assistant, and all the other inhabitants of Stout’s elaborate imaginary world. That’s an awful lot of experts to please.

That Nero Wolfe should be so pleasing has at least as much to do with the casting as the scripts. In addition to co-producing the series and directing several episodes, Timothy Hutton plays Archie Goodwin, and I can’t see how anyone could do a better job. Not only does he catch Archie’s snap-brim Thirties tone with sharp-eared precision, but he also bears an uncanny physical resemblance to the dapper detective-narrator I’ve been envisioning all these years. No sooner did Hutton make his first entrance in The Golden Spiders than he melded completely with the Archie of my mind’s eye. I can no longer read a Stout novel without seeing him, or hearing his voice.

That Nero Wolfe should be so pleasing has at least as much to do with the casting as the scripts. In addition to co-producing the series and directing several episodes, Timothy Hutton plays Archie Goodwin, and I can’t see how anyone could do a better job. Not only does he catch Archie’s snap-brim Thirties tone with sharp-eared precision, but he also bears an uncanny physical resemblance to the dapper detective-narrator I’ve been envisioning all these years. No sooner did Hutton make his first entrance in The Golden Spiders than he melded completely with the Archie of my mind’s eye. I can no longer read a Stout novel without seeing him, or hearing his voice.

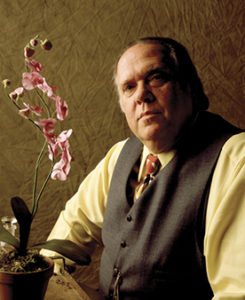

Still, Archie could have wandered out of any number of screwball comedies. Nero Wolfe is a far more complicated proposition. Weighing in at a seventh of a ton, he is a tireless talker endowed with a touch of Johnsonian genius. (It is no small tribute to Stout’s own brainpower that he was capable of making that characterization plausible.) At the same time, he is chronically lazy and neurotic to the highest degree, so much so that he refuses to leave his home on business, preferring to sit at his desk or tend his orchids. Like Sherlock Holmes, the predecessor on whom he was obviously modeled, Wolfe is a misogynist who will have nothing to do with women socially—food, not sex, is his sensual outlet—though every once in a while he gives off a faint but perceptible flicker of interest in one of the pretty ladies who pass through his office.

Maury Chaykin has doubtless immersed himself in the Wolfe novels, for he brings to his interpretation of the part both a detailed knowledge of what Stout wrote and an unexpectedly personal touch of insight. He plays Wolfe as a fearful genius, an aesthete turned hermit who has withdrawn from the world (and from the opposite sex) in order to shield himself—against what? Stout never answers that question, giving Chaykin plenty of room to maneuver, which he uses with enviable skill. His Nero Wolfe is gluttonous, blustery, petulant, even a bit dandyish—but he peers out at his clients through the haunted eyes of a man whwho knows too much.

Chaykin and Hutton are as good in tandem as they are separately, for they understand that the Wolfe books are less mystery stories than domestic comedies, the continuing saga of two iron-willed codependents engaged in an endless game of one-upmanship. Archie may be Wolfe’s hired hand, but he is also an undefinable combination of servant, goad, court jester, and trusted confidant. His relationship with Wolfe is by definition uneasy, intimate but never affectionate—it’s plain to see that he loves Wolfe like a father, but inconceivable that he would ever admit such a thing—and so the intimacy is transformed into a daily contest for dominance. At least half the fun of the Wolfe books comes from the way in which Stout plays this struggle for laughs, and Chaykin and Hutton make the most of it, sniping at each other with naughty glee.

Chaykin and Hutton are as good in tandem as they are separately, for they understand that the Wolfe books are less mystery stories than domestic comedies, the continuing saga of two iron-willed codependents engaged in an endless game of one-upmanship. Archie may be Wolfe’s hired hand, but he is also an undefinable combination of servant, goad, court jester, and trusted confidant. His relationship with Wolfe is by definition uneasy, intimate but never affectionate—it’s plain to see that he loves Wolfe like a father, but inconceivable that he would ever admit such a thing—and so the intimacy is transformed into a daily contest for dominance. At least half the fun of the Wolfe books comes from the way in which Stout plays this struggle for laughs, and Chaykin and Hutton make the most of it, sniping at each other with naughty glee.

The other continuing characters have been cast almost as deftly, especially Bill Smitrovich as the long-suffering Inspector Cramer, who spends most of his on-screen time yelling vainly at Wolfe, and Colin Fox as Fritz, Wolfe’s live-in chef, who tolerates the great man’s tantrums without stooping to subservience. Most of the secondary characters are drawn from a stock company of little-known performers who do an excellent job of changing hats from week to week. (Guest stars are rare, though George Plimpton pops up now and then, usually as a WASP lawyer.) Best of all is Kari Matchett, a jolie laide with a sharp nose and a long neck who specializes in femmes fatales of various kinds, as well as playing Lily Rowan, Archie’s on-again-off-again ladyfriend. Be she victim or villain, she is at all times funny, sexy, and a wicked scene-stealer.

Like so many other TV series and movies purporting to be set in New York, Nero Wolfe is in fact shot in Toronto on a very low budget, most of which appears to have been spent on period costumes and a painstakingly detailed, near-impeccable reproduction of Wolfe’s office, in which roughly a third of each episode takes place. The other sets are built on the cheap, and the exteriors don’t even attempt to look authentic—a major failing of the series, since Stout’s novels are as redolent of Manhattan as Raymond Chandler’s are of Los Angeles—while anyone closely familiar with the original novels will have no trtrouble spotting occasional solecisms. (Wolfe would never listen to classical music at mealtime, if ever!)

Needless to say, none of this matters in the slightest. Like all good detective stories, the Nero Wolfe novels are not primarily about their settings, or even their plots. They are conversation pieces, witty studies in human character, and for all its flaws of execution, A&E’s Nero Wolfe never fails to bring its principal characters to life. I can’t say whether it will appeal to those who aren’t already members of the Wolfe pack, but speaking as a hopeless addict who bought his first Rex Stout paperback at the age of thirteen, I’m already looking forward to the third season.

* * *

“The Golden Spiders,” the pilot for A Nero Wolfe Mystery:

The John Kirby Sextet plays Charlie Shavers’ “Musicomania” in Sepia Cinderella, directed by Arthur Leonard and released in 1947. The band consists of Buster Bailey on clarinet, Charlie Holmes on alto saxophone, Shavers on trumpet, Billy Kyle on piano, Kirby on bass, and Big Sid Catlett on drums:

The John Kirby Sextet plays Charlie Shavers’ “Musicomania” in Sepia Cinderella, directed by Arthur Leonard and released in 1947. The band consists of Buster Bailey on clarinet, Charlie Holmes on alto saxophone, Shavers on trumpet, Billy Kyle on piano, Kirby on bass, and Big Sid Catlett on drums:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I offer some further thoughts on the wider implications of the James Levine scandal. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Few doubt that Mr. Levine’s performing career is over, regardless of whether he is in legal jeopardy. But what of his artistic legacy? Will his musical achievements be forgotten as a result of his disgrace? Not only has he recorded extensively for the past four decades, but audio and video recordings of his broadcast performances with the Met continue to be widely available. Will this continue to be true—and should it? Or is Mr. Levine’s work destined to vanish into the memory hole?…

Few doubt that Mr. Levine’s performing career is over, regardless of whether he is in legal jeopardy. But what of his artistic legacy? Will his musical achievements be forgotten as a result of his disgrace? Not only has he recorded extensively for the past four decades, but audio and video recordings of his broadcast performances with the Met continue to be widely available. Will this continue to be true—and should it? Or is Mr. Levine’s work destined to vanish into the memory hole?…

It is mostly taken for granted by aesthetes that the creative achievements of a morally flawed artist can and should be judged separately from his offstage conduct. (Two words: Pablo Picasso.) According to William Faulkner, “If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ is worth any number of old ladies.”

Laymen have always been understandably uncomfortable with this belief, for the very good reason that it encourages us to treat great artists as privileged creatures inhabiting a moral realm above and beyond that of the rest of us. For me, Faulkner’s oft-quoted apothegm is at the very least arguable—but with one essential caveat: No matter how beautiful or profound the results may be, the artist who robs his mother should do time for it. He must be subject to the inexorable operation of the moral law.

Consider the case of Herbert von Karajan. He was one of the greatest orchestral conductors of the 20th century. He was also in his youth a member of the Nazi party, which he joined in 1933 to further his career. How should that affect our feelings about his work?…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

James Levine and the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra perform the overture from Verdi’s La Forza del Destino:

Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic perform the same work:

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

BROADWAY:

• The Band’s Visit (musical, PG-13, all shows sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Dear Evan Hansen (musical, PG-13, all shows sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Hamilton (musical, PG-13, Broadway transfer of off-Broadway production, all shows sold out last week, reviewed here)

CLOSING SATURDAY OFF BROADWAY:

• Pride and Prejudice (comedy, G, remounting of Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival production, original production reviewed here)

An ArtsJournal Blog