The fool is happy that he knows no more.

The fool is happy that he knows no more.

Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

A friend sent me a review of Night Trains, a new book by Andrew Martin about the rise and fall of Europe’s once-celebrated luxury sleeper trains:

A friend sent me a review of Night Trains, a new book by Andrew Martin about the rise and fall of Europe’s once-celebrated luxury sleeper trains:

Martin is particularly good at describing these night trains in their pomp, when they were the best, and sometimes the only, way of getting round Europe reasonably fast. However, the service declined markedly from the 1970s, and what had been a service aimed at Europe’s elite became a very mundane one. My experience on the Orient Express in 2006, three years before it was finally killed off, was typical: the only food available was the worst crustless white plastic cheese sandwich I have ever eaten. A desperate raid of the automatic machines on Strasbourg station yielded only nuts.

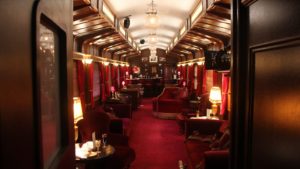

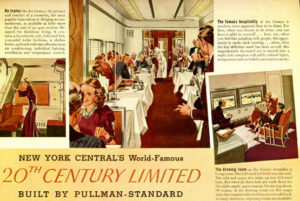

When it comes to night trains, I share the sentiments of Martin and Christian Wolmar, the reviewer, enough so that Mrs. T and I went so far two years ago as to take a sleeper from New York to Florida and back, an experience that I wrote about here and here. But unlike my first trip on a sleeper, this one was a disappointment, enough so to make it unlikely that I’ll ever do it again. I fear that I’d read far too much about the great trains of the past, and seen too many of them lovingly portrayed by Hollywood, to be capable of appreciating the much-diminished charms of their latter-day descendants.

When it comes to night trains, I share the sentiments of Martin and Christian Wolmar, the reviewer, enough so that Mrs. T and I went so far two years ago as to take a sleeper from New York to Florida and back, an experience that I wrote about here and here. But unlike my first trip on a sleeper, this one was a disappointment, enough so to make it unlikely that I’ll ever do it again. I fear that I’d read far too much about the great trains of the past, and seen too many of them lovingly portrayed by Hollywood, to be capable of appreciating the much-diminished charms of their latter-day descendants.

Hence I confess to a certain skepticism about the trustworthiness of Wolmar, who claims in his review that “Amtrak, the state-owned railway in the USA, runs a series of very comfortable long-distance overnight trains.” If Amtrak is his idea of comfort…well, let’s say I don’t share it, and leave it there.

To be sure, I still love trains—or, rather, the idea of trains—and I expect I always will. All my life I’ve found the sound of train whistles almost unbearably evocative. As I once wrote in this space:

My brother tells me that more freight trains have been passing through Smalltown lately, and though the tracks are halfway across town from my mother’s house, you can still hear the whistles loud and clear. My mother thinks they sound mournful, but I never thought so. They used to make me curious about the big world somewhere down the track, and now that I live in that big world, they remind me that I have things to do back there.

Small wonder that I was an ardent fan of The Wild Wild West, a TV series of the Sixties whose nineteenth-century protagonists traveled from caper to caper on a private train. Ever since then I’ve dreamed in vain of doing the same thing. While Mrs. T and I were in Sarasota earlier this month, we visited the Ringling Museum, whose exhibits include the resplendent private car on which John and Mable Ringling traveled throughout America, and my childhood dreams sprung to life once more.

Small wonder that I was an ardent fan of The Wild Wild West, a TV series of the Sixties whose nineteenth-century protagonists traveled from caper to caper on a private train. Ever since then I’ve dreamed in vain of doing the same thing. While Mrs. T and I were in Sarasota earlier this month, we visited the Ringling Museum, whose exhibits include the resplendent private car on which John and Mable Ringling traveled throughout America, and my childhood dreams sprung to life once more.

Alas, the American Orient Express went bankrupt before I could book a trip to nowhere, and I doubt I’ll get another chance to relive the good old days of luxury train travel. Not enough Americans love trains to make it worth anybody’s while anymore. Unlike me, they see them as slow, bumpy, exasperatingly uncomfortable ways of getting from point A to point B, not as the miraculous vehicles of romance about which Johnny Mercer and Jimmy Van Heusen wrote so evocatively and well:

I took a trip on a train

And I thought about you.

We passed a shadowy lane,

And I thought about you.

Two or three cars

Parked under the stars,

A winding stream.

Moon shining down

On some little down.

With each beam,

Same old dream.

With every stop that we made,

I thought about you.

And then I pulled down the shade

And I really felt blue.

I peeked through the crack

And looked at the track,

The one going back

To you.

And what did I do?

I thought about you.

That’s how I feel about trains.

* * *

The Miles Davis Quintet plays “I Thought About You” in 1961:

The day after Harry Truman finally returned home to Independence, Missouri, a reporter asked him what he planned to do first. “Carry the grips up to the attic,” he replied. It’s a wonderful line, one that says everything about what it means to come from a place like Missouri. The catch, of course, is that you have to have an attic, a place where you can store a baseball signed by Stan Musial and know that it’ll still be there when, a half century later, you feel like taking it out and looking at it….

Read the whole thing here.

Mrs. T and I flew up to Hartford on Saturday night and made our way from the airport to the Connecticut farmhouse in which we live, bringing to a close our annual trip to Florida.

Mrs. T and I flew up to Hartford on Saturday night and made our way from the airport to the Connecticut farmhouse in which we live, bringing to a close our annual trip to Florida.

We had a happy time down south, as we always do, and I got a lot of work done while we were there, as I always do. Not only did I review several fine shows, but I spent three satisfying days workshopping my own new play, whose premiere was announced in January. Somewhere along the way, we both got to feeling as though we’d be perfectly happy to stay in Florida forever, driving from show to show and living out of suitcases. But come Saturday, we were more than ready to head home, unpack our bags, sleep in our own beds, and resume our regular lives.

I almost said “normal” instead of “regular,” but then I remembered the wise words that Doc Holliday spoke to Wyatt Earp in Tombstone: “There is no normal life, there’s just life.” It’s as “normal” for the two of us to stroll up and down the beaches of Sanibel island in January as it is for us to turn up the heat in Connecticut, nestle on the couch, and watch old movies together in March. Still, there comes a time when you want to return to a place where you can find the light switches in the dark, and that time has come. Cold as it is up here in the country, we’ve done enough traveling to hold us for a while.

I’ll be spending the next two months covering New York theater openings, of which there are far too many this spring, and we won’t be hitting the road again until the season ends. Instead we’ll content ourselves with shuttling between Manhattan and Connecticut and making plans for our summer travels, which will be, as usual, extensive. And sooner or later we’ll look up at each other and say, “It’ll be nice to get back to Florida again, won’t it?” And so it will be. Home is wherever we both are, ever and always.

* * *

Nickel Creek perform Bob Dylan’s “Tomorrow Is a Long Time” in Boston in 2014:

Victor 18255-A, the first jazz record, was cut in New York one hundred years ago yesterday, five years after the word “jazz” first appeared in print. On it, the Original Dixieland Jass Band, a group of five white musicians from New Orleans, can be heard playing Dixie Jass Band One-Step and Livery Stable Blues, a pair of more or less original tunes.

Victor 18255-A, the first jazz record, was cut in New York one hundred years ago yesterday, five years after the word “jazz” first appeared in print. On it, the Original Dixieland Jass Band, a group of five white musicians from New Orleans, can be heard playing Dixie Jass Band One-Step and Livery Stable Blues, a pair of more or less original tunes.

Contrary to the claims of Nick LaRocca, the band’s cornet player, the ODJB didn’t “invent” jazz—nobody did, really, least of all Jelly Roll Morton, who made the same claim—but its recordings played a pivotal role in popularizing and disseminating what soon came to be generally recognized as one of America’s first wholly original styles of music. As I wrote in Pops, my biography of Louis Armstrong:

The records made by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band…sound like jazz as we know it, primitive but recognizable, with the now-familiar front line of clarinet, cornet, and trombone playing the loosely woven, rough-and-ready counterpoint that would soon become known the world over. We have it on the best authority that they were recognized as such in their makers’ home town, for Louis Armstrong listened to “Livery Stable Blues” and “Tiger Rag” on his first phonograph, along with the opera arias whose Italianate ardor and showy virtuosity also left their mark on his style. “Between you and me, it’s still the best,” he wrote in Satchmo of the ODJB’s 1918 recording of “Tiger Rag.”

I rarely listen to the ODJB’s records for pleasure, and when I do, I’m more likely to opt for the electrically recorded remakes of its acoustic 78 sides that the band cut in 1936, which are much clearer-sounding and closely similar in style to the originals. Nevertheless, I do get pleasure out of them, for they are raucously vivid and vital souvenirs of jazz when it was still fresh from the cradle.

Nor do I lose any sleep over LaRocca’s oft-quoted, patently preposterous claim that “the Negroes learned to play this rhythm and music from the whites,” which is reflexively trotted out whenever the ODJB’s name is mentioned by those who are more interested in politics than music. LaRocca was, of course, talking through his hat—but what of it? The inescapable fact remains that the ODJB, for whatever reason or reasons, made it into the studio before anybody else, and the records they cut there were more than good enough to open the ears of the world.

A century later, jazz is no longer a popular music, a fact about which I wrote to controversial effect in 2009:

As late as the early ’50s, jazz was still for the most part a genuinely popular music, a utilitarian, song-based idiom to which ordinary people could dance if they felt like it. But by the ’60s, it had evolved into a challenging concert music whose complexities repelled many of the same youngsters who were falling hard for rock and soul. Yes, John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” sold very well for a jazz album in 1965—but most kids preferred “California Girls” and “The Tracks of My Tears,” and still do now that they have kids of their own.

That’s as true today as it was eight years ago, La La Land and Whiplash notwithstanding, and I don’t expect the situation to change in my lifetime. Be that as it may, jazz—great jazz—is still being played in New York and all over the world, and I don’t expect that to change any time soon, either.

That’s as true today as it was eight years ago, La La Land and Whiplash notwithstanding, and I don’t expect the situation to change in my lifetime. Be that as it may, jazz—great jazz—is still being played in New York and all over the world, and I don’t expect that to change any time soon, either.

I was a professional jazz musician once upon a time, and my involvement in jazz continues to this day, albeit as a journalist, biographer, and playwright rather than a performer. Hardly a day goes by on which I don’t listen to at least one jazz record, usually on my MacBook, to which I have uploaded thousands of the performances I love best. I have no “favorite” kind of music, but I simply can’t imagine a world without the particular kind of music to which I have happily devoted so much of my life.

As Philip Larkin said of the records of Sidney Bechet, one of the first great jazz musicians:

On me your voice falls as they say love should,

Like an enormous yes. My Crescent City

Is where your speech alone is understood,

And greeted as the natural noise of good,

Scattering long-haired grief and scored pity.

Blessings, then, on the members of the Original Dixieland Jass Band, who first spoke the enormous yes of jazz into the horn of a recording machine. We have been in their debt for a century now. May we remain so throughout the century to come.

* * *

The surviving members of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band recreate their first recording session in a 1937 March of Time newsreel:

Eddie Edwards and Tony Sbarbaro, the original trombonist and drummer of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, appear as guests on an episode of I’ve Got a Secret originally telecast on CBS on November 9, 1960. Their “secret” was that they had made the first jazz record in 1917. (Sbarbaro subsequently changed his last name to “Spargo.”) After stumping the panel, they play “Original Dixieland One-Step” with Phil Napoleon, Tony Parenti, and J. Russel Robinson, all of whom worked with the band at various times:

Leontyne Price and Peter Ustinov appear as the mystery guests on What’s My Line? This episode was originally telecast by CBS on September 18, 1966, two days after Price starred in the world premiere of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra at the opening of the new Metropolitan Opera House in New York. The panelists are Woody Allen, Bennett Cerf, Arlene Francis, and Phyllis Newman and the host is John Charles Daly:

Leontyne Price and Peter Ustinov appear as the mystery guests on What’s My Line? This episode was originally telecast by CBS on September 18, 1966, two days after Price starred in the world premiere of Samuel Barber’s Antony and Cleopatra at the opening of the new Metropolitan Opera House in New York. The panelists are Woody Allen, Bennett Cerf, Arlene Francis, and Phyllis Newman and the host is John Charles Daly:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||

An ArtsJournal Blog