“The march of science and technology does not imply growing intellectual complexity in the lives of most people. It often means the opposite.”

“The march of science and technology does not imply growing intellectual complexity in the lives of most people. It often means the opposite.”

Thomas Sowell, Knowledge and Decisions

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

I recently received in the mail an advance copy of the Bill Charlap Trio’s upcoming CD, a live album recorded at the Village Vanguard. (Blue Note will be releasing it in May.) I happened to be on hand for one of the sets taped for inclusion in this album. Sometimes the heat of the moment can fool you into thinking that a live performance is better than it is, so I was delighted, though not surprised, to hear that this one was every bit as good as I’d remembered.

I’ve lived in New York for a quarter-century and spent a considerable number of my nights on the town, so it’s not surprising that I’ve been present at the creation of a fair number of noteworthy live albums. After scanning my memory and my record shelves, I came up with six others…

Read the whole thing here.

“I don’t say that we artists are more intelligent or that we know more than everybody else. Not at all. It’s just that we have more time, and we’ve dedicated our time to the search for truth. All the other people, after all, have to work to make a living as bankers, state employees, or railroad engineers. When we artists discover a little bit of truth, well, we open a new window and show new landscape, and people are thankful to us for that. They say: ‘But that’s the truth!’ And it’s even truer, because the landscape we discover, the landscape we show, is one they already know. But they never saw it in that way before.”

“I don’t say that we artists are more intelligent or that we know more than everybody else. Not at all. It’s just that we have more time, and we’ve dedicated our time to the search for truth. All the other people, after all, have to work to make a living as bankers, state employees, or railroad engineers. When we artists discover a little bit of truth, well, we open a new window and show new landscape, and people are thankful to us for that. They say: ‘But that’s the truth!’ And it’s even truer, because the landscape we discover, the landscape we show, is one they already know. But they never saw it in that way before.”

Jean Renoir, interviewed by Gideon Bachmann (Contact, June 1960)

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the Broadway revival of Miss Saigon. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

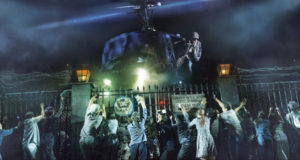

“Miss Saigon,” in which Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil, the makers of “Les Misérables,” turned “Madame Butterfly” into a mega-budget musical, is back on Broadway for the first time since 2001. Then as now, the first thing people mention whenever they talk about “Miss Saigon” is the helicopter. Rightly so, too, for that now-legendary onstage prop, the deus ex machina that rescues the show’s sort-of-antihero, was Broadway’s Giant Rubber Shark. It remains to this day a symbol of the scenic excesses of the imported West End musical extravaganzas of the ’80s, which did to the Broadway musical what “Jaws” did to Hollywood movies….

How does “Miss Saigon” look and sound today? Well, there’s still a helicopter, and if you like fake helicopters, this one is way big, way loud and—I can’t deny it—way cool. On the other hand, the Asian characters are all played this time around by actors of Asian descent, for “woke” progressives now look upon “yellowface,” as the casting of white actors in Asian roles has come to be called, as an unpardonable sin. In addition, other small changes, none of which you’ll notice unless you look really hard, have been made to bring the show into line with latter-day ethnic sensitivities. Otherwise, it’s the same old “Miss Saigon,” a two-hour-and-40-minute pop opera in which the well-worn ugly-American plot of “Madame Butterfly” (an American soldier meets, falls in love with and impregnates an Asian prostitute, then returns home and marries a white woman, not knowing that he has left behind a mixed-race child) is updated and transplanted from Japan to Vietnam in order to portray the defeat of U.S. power in southeast Asia.

How does “Miss Saigon” look and sound today? Well, there’s still a helicopter, and if you like fake helicopters, this one is way big, way loud and—I can’t deny it—way cool. On the other hand, the Asian characters are all played this time around by actors of Asian descent, for “woke” progressives now look upon “yellowface,” as the casting of white actors in Asian roles has come to be called, as an unpardonable sin. In addition, other small changes, none of which you’ll notice unless you look really hard, have been made to bring the show into line with latter-day ethnic sensitivities. Otherwise, it’s the same old “Miss Saigon,” a two-hour-and-40-minute pop opera in which the well-worn ugly-American plot of “Madame Butterfly” (an American soldier meets, falls in love with and impregnates an Asian prostitute, then returns home and marries a white woman, not knowing that he has left behind a mixed-race child) is updated and transplanted from Japan to Vietnam in order to portray the defeat of U.S. power in southeast Asia.

I became a drama critic two years after “Miss Saigon” closed on Broadway, and I’ve never had any occasion to seek it out since then. I came fresh to it, just as I came fresh to “Les Miz” when I saw and panned the 2006 Broadway revival. Alas, I feel pretty much the same way about “Miss Saigon.” Like “Les Miz,” it’s an opera for the tone-deaf: The dramatic gestures are broad and banal and the faux-rock songs are exercises in louder-is-betterness whose tunes go round and round in tight little circles of melodic monotony….

Laurence Connor, the director, and Totie Driver and Matt Kinley, the production designers, have served the show faithfully and well, while Alistair Brammer, Jon Jon Briones and Eva Noblezada, all of whom previously starred in the London run, give effective performances. I suppose it wouldn’t be fair to hold against any of them the fact that “Miss Saigon” and its predecessors hollowed out the Broadway musical as a creative enterprise by replacing theatrical imagination with top-dollar spectacle. They’re just—you might say—following orders….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Mary Martin appears as Emily in a scene from Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. The scene is introduced by Oscar Hammerstein II, who also plays the role of the Stage Manager. This performance was originally seen on The Ford 50th Anniversary Show, directed by Jerome Robbins and simulcast by CBS and NBC on June 15, 1953:

Mary Martin appears as Emily in a scene from Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. The scene is introduced by Oscar Hammerstein II, who also plays the role of the Stage Manager. This performance was originally seen on The Ford 50th Anniversary Show, directed by Jerome Robbins and simulcast by CBS and NBC on June 15, 1953:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“The awful thing about the cinema is the possibility of moving about exactly as one wants. You say, ‘Well, I must explain this emotion, and I’ll do it by going into flashback and showing you what happened to this man when he was two years old.’ It’s very convenient, of course, but it’s also enfeebling. If you have to make the emotion understood simply through his behavior, then the discipline brings a kind of freedom with it. There’s really no freedom without discipline, because without it one falls back on the disciplines one constructs for oneself, and they are really formidable. It’s much better if the restraints are imposed from the outside.”

“The awful thing about the cinema is the possibility of moving about exactly as one wants. You say, ‘Well, I must explain this emotion, and I’ll do it by going into flashback and showing you what happened to this man when he was two years old.’ It’s very convenient, of course, but it’s also enfeebling. If you have to make the emotion understood simply through his behavior, then the discipline brings a kind of freedom with it. There’s really no freedom without discipline, because without it one falls back on the disciplines one constructs for oneself, and they are really formidable. It’s much better if the restraints are imposed from the outside.”

Jean Renoir, interviewed by Louis Marcorelles (Sight and Sound, Spring 1962)

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

An ArtsJournal Blog