“Man is the only animal that laughs and weeps; for he is the only animal that is struck with the difference between what things are, and what they ought to be.”

“Man is the only animal that laughs and weeps; for he is the only animal that is struck with the difference between what things are, and what they ought to be.”

William Hazlitt, Lectures on the English Comic Writers

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

In today’s Wall Street Journal I report on the premiere of Kate Hamill’s stage version of Vanity Fair. Here’s an excerpt.

In today’s Wall Street Journal I report on the premiere of Kate Hamill’s stage version of Vanity Fair. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“Vanity Fair,” in which William Makepeace Thackeray recorded the adventures of Becky Sharp, a young woman who is prepared to do pretty much anything in order to claw her way to the top of Victorian England’s greasy pole of success, isn’t quite so widely read in the U.S. as it used to be. Nevertheless, it remains one of the 19th century’s most enduringly popular novels, and it’s amazing that no one seems to have successfully brought it to the stage until now. Enter Kate Hamill, whose 2014 Bedlam Theatre Company adaptation of “Sense and Sensibility” was a well-deserved success and who has now turned Thackeray’s 1848 “novel without a hero” into a play. I’m suspicious as a rule of stage versions of classic novels, which are in most cases pointless attempts to “repurpose” a beloved book for purposes of profit. But Ms. Hamill’s “Vanity Fair,” which is being performed to coruscatingly brilliant effect by the Pearl Theatre Company, is something else again, a masterpiece of creative compression…

The plot of “Vanity Fair” is far too labyrinthine to summarize neatly. Suffice it to say that Becky (played by Ms. Hamill herself) and her best friend Amelia (Joey Parsons) seek to stay afloat in a society that has little to offer women with neither wealth nor position. Amelia, being fundamentally good at heart, sticks to the straight and narrow path of virtue, but the amoral, ruthlessly realistic Becky is more inclined to take the advice of one of the various protectors who take an interest in her progress through life: “Never be too good, nor too bad. The world will punish you for both. Try to pace right with the rest of us in the unnoticeable hypocritical middle.”…

Ms. Hamill has envisioned “Vanity Fair” as a show performed by “a seedy band of roving actors, putting on a play with minimum effort.” The set, ingeniously designed by Sandra Goldmark, is a rundown theater dressed with the miscellaneous leavings of forgotten productions. In addition to Becky and Amelia, five men (Zachary Fine, Brad Heberlee, Tom O’Keefe, Debargo Sanyal and Ryan Quinn) divvy up 17 speaking roles between them, dressing and cross-dressing in full view of the audience…

Ms. Hamill has envisioned “Vanity Fair” as a show performed by “a seedy band of roving actors, putting on a play with minimum effort.” The set, ingeniously designed by Sandra Goldmark, is a rundown theater dressed with the miscellaneous leavings of forgotten productions. In addition to Becky and Amelia, five men (Zachary Fine, Brad Heberlee, Tom O’Keefe, Debargo Sanyal and Ryan Quinn) divvy up 17 speaking roles between them, dressing and cross-dressing in full view of the audience…

Eric Tucker, the director, is the co-founder of Bedlam Theatre Company, of which Ms. Hamill is also a member. As regular readers of this column will recall, I rank Mr. Tucker alongside David Cromer at the pinnacle of the short list of America’s most imaginative stage directors, and save for the fact that it’s being presented on a proscenium stage, his “Vanity Fair” has all the hallmarks of a Bedlam production. The quick-change shape-shifting of the cast, the outrageous physical comedy of the staging, the startlingly witty use of props: All are Mr. Tucker’s now-familiar trademarks, and all add immeasurably to the show’s impact….

Ms. Hamill’s Becky is a saucy, spunky schemer who, as the Victorians liked to say, is no better than she has to be. As for Ms. Parsons, one of my favorite New York-based actors, she has a genius for endowing seemingly thankless straight-man female parts with a warmth and emotional intensity that make them memorable….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

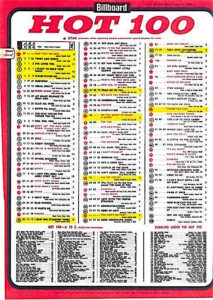

This is Billboard’s Hot 100 chart for April 4, 1964. All of the top five singles on the chart were recorded by the Beatles, along with seven other lower-ranked singles (plus two musical tributes to the group, “A Letter to the Beatles” and “We Love You Beatles”). At no time before or since has one group or solo artist dominated the pop-music charts so completely.

This is Billboard’s Hot 100 chart for April 4, 1964. All of the top five singles on the chart were recorded by the Beatles, along with seven other lower-ranked singles (plus two musical tributes to the group, “A Letter to the Beatles” and “We Love You Beatles”). At no time before or since has one group or solo artist dominated the pop-music charts so completely.

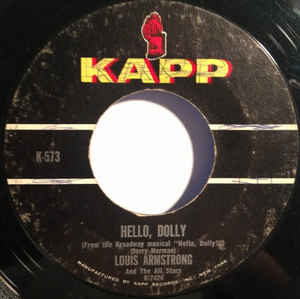

Just as interesting, though, is the fact that Louis Armstrong’s recording of “Hello, Dolly!” occupied the #7 slot on the chart that week. Five weeks later, it would knock “Can’t Buy Me Love” out of the top position, succumbing a week later to Mary Wells’ “My Guy.” Never again would a jazz record top the Billboard charts, and only one other show tune, “Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In,” has since gone all the way to #1.

These facts are striking enough as is. But a closer look at the April 4 chart reveals that it contains:

• No jazz records other than “Hello, Dolly!”

• Only one other record of a show tune, Barbra Streisand’s “People,” all the way down at #100

• Only three other “standards” singers, Al Martino at #23 (with a pseudo-country tune), Jack Jones at #62, and Gloria Lynne at #82 with “I Should Care,” written in 1944

• Only one record by a big band, Sammy Kaye’s rock-flavored Muzak-style version of Henry Mancini’s “Charade,” at #89

In their place are the Beach Boys, the Dave Clark Five, the Four Seasons, Jan and Dean, Lesley Gore, Elvis Presley, and Bobby Vinton.

Not only were jazz and golden-age standards no longer a significant part of the American pop-music scene in 1964, but every other musical style had been pushed into the shadows by the rise of rock. Look at the chart and you will see:

Not only were jazz and golden-age standards no longer a significant part of the American pop-music scene in 1964, but every other musical style had been pushed into the shadows by the rise of rock. Look at the chart and you will see:

• One folk group, Peter, Paul & Mary at #33

• Two country singers, Johnny Cash at #43 and Johnny Tillotson at #54

• Two quasi-country instrumental novelties, Pete Drake’s “Forever” at #44 and Boots Randolph’s “Hey, Mr. Sax Man” at #99

• Four non-rock pop instrumentals, Al Hirt’s “Java” at #18, Robert Maxwell’s “Shangri-La” at #60, Henry Mancini’s “Pink Panther Theme” (a genuinely jazzy record with a tenor-sax solo by Plas Johnson) at #80, and Herb Alpert’s “Mexican Drummer Man” at #91

• One R&B instrumental, King Curtis’ “Soul Serenade” at #86

And what of black pop music? Well, you’ll find Ray Charles, Marvin Gaye, Mary Wells, Otis Redding, the Temptations, and “Little Stevie Wonder” (as he was known in his youth) on the April 4 Hot 100 chart, plus a fair number of records by such vocal groups as the Coasters, the Contours, the Impressions, the Marvelettes, the Miracles, the Raindrops, the Ronettes, and the Shirelles. But nearly all of these records are on the bottom half of the chart, which suggests that they were mostly being bought by black listeners in 1964, in much the same way that the now-legendary “race” records of the Twenties were largely unknown to white listeners. And it is just as noteworthy that only two blues records, Bobby “Blue” Bland’s “Ain’t Nothing You Can Do” and B.B. King’s “How Blue Can You Get,” made it onto the chart.

The Beatles were not responsible for this transformation. The Hot 100 charts for 1959 were broadly similar-looking, if not quite so stylistically homogenous. The juggernaut of rock had rolled over and flattened out the American musical landscape well before the Beatles came along. But their colossal success, in addition to ratifying the triumph of rock, is yet another indication that America still had a common culture in 1964. To glance at the April 4 Hot 100 chart is to be left in no possible doubt that pretty much everybody in America was listening to the Beatles that week, just as pretty much everybody was watching The Beverly Hillbillies and Bonanza on TV.

The Beatles were not responsible for this transformation. The Hot 100 charts for 1959 were broadly similar-looking, if not quite so stylistically homogenous. The juggernaut of rock had rolled over and flattened out the American musical landscape well before the Beatles came along. But their colossal success, in addition to ratifying the triumph of rock, is yet another indication that America still had a common culture in 1964. To glance at the April 4 Hot 100 chart is to be left in no possible doubt that pretty much everybody in America was listening to the Beatles that week, just as pretty much everybody was watching The Beverly Hillbillies and Bonanza on TV.

For better and worse, we were all on the same page in 1964, the year in which Philip Larkin wrote “MCMXIV,” a poem about what England had been like fifty years earlier, on the eve of World War I:

Never such innocence,

Never before or since,

As changed itself to past

Without a word—the men

Leaving the gardens tidy,

The thousands of marriages,

Lasting a little while longer:

Never such innocence again.

* * *

The Beatles perform “Twist and Shout” on The Ed Sullivan Show on February 23, 1964. The song, recorded on February 11 and released as a single in the U.S. on March 2, reached #2 on Billboard’s Hot 100 chart on April 4:

As a child I watched Kitty Carlisle on To Tell the Truth, the classic game show that introduced me to the word “affidavit,” and a little later I saw A Night at the Opera for the first time and was amazed to find that the distinguished and amusing lady who sat on a TV panel every afternoon had once been a movie star of sorts. Later on I played Beverly Carlton in a college production of The Man Who Came to Dinner and discovered to my further amazement that she was the widow of its co-author, Moss Hart.

It hardly seemed possible that such a self-evidently historic person as Kitty Carlisle Hart (as she now styled herself) should still be alive when I finally made it to New York twenty-two years ago, but she sure enough was, having outlived her far more famous husband to become one of the last surviving relics of an age in which I would have preferred to live….

Read the whole thing here.

“In a courtroom everything becomes quite different from what it is. I’ve always greatly admired, for example, the sheer intellectual achievement of a good summing-up. But it comes to my mind now I’ve heard litigants say, when you know what really happened it sounds like the ravings of delirium. You lawyers are not appreciated: you’re the great creative artists of the age!”

“In a courtroom everything becomes quite different from what it is. I’ve always greatly admired, for example, the sheer intellectual achievement of a good summing-up. But it comes to my mind now I’ve heard litigants say, when you know what really happened it sounds like the ravings of delirium. You lawyers are not appreciated: you’re the great creative artists of the age!”

Honor Tracy, The Straight and Narrow Path

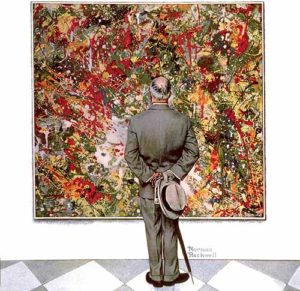

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I write about Slow Art Day. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Saturday is Slow Art Day, an annual event in which 156 museums and art galleries in the U.S. and around the world are participating this year. Here’s how it works:

• Sign up at a local museum or gallery. (You can do so here.)

• Show up on Saturday, then “look slowly—5-10 minutes—at each piece of pre-assigned art.”

• Show up on Saturday, then “look slowly—5-10 minutes—at each piece of pre-assigned art.”

• Discuss your experience with other participants. Each institution has its own arrangements for doing so, but “what all the events share is the focus on slow looking and its transformative power.”…

I think Phil Terry, the founder of Slow Art Day, is onto something important. As he explained in a 2011 interview with ARTnews magazine, “My wife kept dragging me to museums. I didn’t know how to look at art. Like most people, I would walk by quickly.” Then he spent a full hour looking at “Fantasia,” a spectacularly complex 1943 abstract painting by Hans Hofmann that belongs to the University of California’s Berkeley Art Museum, and found the unfamiliar experience to be galvanizing. According to one survey, most people spend roughly 17 seconds looking at each individual painting during a museum visit. That’s why Mr. Terry started Slow Art Day—to encourage all of us to slow down and see more of what’s there to be seen in a great work of art….

I am, I blush to admit, a bit of a galloper when it comes to museumgoing, just as I habitually eat too fast. On the other hand, I also collect art, and I’ve learned from doing so that the more time you spend looking at a painting of quality, the more fully it reveals its secrets, in much the same way that you come to understand a novel more completely by re-reading it. This is true of all important art, regardless of medium…

I am, I blush to admit, a bit of a galloper when it comes to museumgoing, just as I habitually eat too fast. On the other hand, I also collect art, and I’ve learned from doing so that the more time you spend looking at a painting of quality, the more fully it reveals its secrets, in much the same way that you come to understand a novel more completely by re-reading it. This is true of all important art, regardless of medium…

The difference—at least in theory—is that performed art, unlike visual art, must be experienced across a pre-defined span of time. It takes a half-hour, more or less, to listen to a symphony by Mozart or Haydn, and the only way to speed up the process is to get up and leave the hall. Unfortunately, a fast-growing number of people now do most of their listening on computers and hand-held devices of various kinds. Even for a seasoned music lover, the temptation to click from piece to piece in search of instant gratification can be overwhelming…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

In Saturday’s Wall Street Journal “Masterpiece” column I wrote about Paul Rudolph’s Walker Guest House, located on Florida’s Sanibel Island, and the replica of the house that was built two years ago on the grounds of Sarasota’s Ringling Museum of Art. Here’s an excerpt.

In Saturday’s Wall Street Journal “Masterpiece” column I wrote about Paul Rudolph’s Walker Guest House, located on Florida’s Sanibel Island, and the replica of the house that was built two years ago on the grounds of Sarasota’s Ringling Museum of Art. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

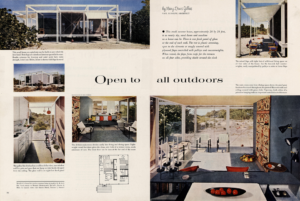

Most Americans are more than happy to live in houses all but indistinguishable from the ones occupied by their next-door neighbors. You can drive for miles on Florida’s Sanibel Island, a resort-and-retirement spot on the Gulf of Mexico, without seeing a home that stands out from the beach bungalows, ranch houses and Spanish Colonial mini-mansions that line the roads. But Paul Rudolph’s Walker Guest House, built there in 1952-53 and still owned by one of its original occupants, is a spectacular exception to the rule of comfortable conformity that dominates American domestic architecture.

A 576-square-foot “tiny house” that predates by a half-century the current craze for scaled-down dwellings, it’s a glass-and-wood beach cottage designed in the severely elegant style of Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House and Philip Johnson’s Glass House. Sixty-five years after it was built, the Walker Guest House remains startlingly contemporary. Rudolph himself said that it “crouches like a spider in the sand.” Yet the uncluttered interior is bright, airy and paradoxically spacious-looking, and you needn’t be addicted to midcentury modernism to find it not just beautiful but lovable.

Frugally constructed out of inexpensive ready-made materials that could be shipped by ferry to Sanibel Island from the nearest lumberyard, the Walker Guest House consists of a 24-foot-wide living-and-dining area, a simple galley kitchen, a cozy bedroom and a shower-only bathroom, all of them suspended 18 inches off the house’s seaside bed of crushed oyster shells. Walt Walker, a Minneapolis doctor who was recovering from tuberculosis and found it hard to cope with Minnesota’s lethal snowstorms, commissioned it as a warm-weather retreat for himself and his wife. Accordingly, the house was deliberately designed to minimize the distinction between inside and outside. But unlike the Mies and Johnson houses, whose floor-to-ceiling glass walls deprive their occupants of privacy, the air-cooled interior is protected from the eyes of strangers by eight huge top-hinged plywood flaps, each one counterbalanced by a cannonball-like 77-pound iron weight, that can be raised and lowered by hand from inside the building….

Today Rudolph, who died in 1997, is best remembered for his public buildings in the now-unfashionable “brutalist” style, many of which have either been torn down or are earmarked for demolition. But it was his Florida vacation homes that put him on the map, so much so that the Walker Guest House was the subject of an enthusiastic 1954 two-page spread in McCall’s (“This small summer house…is as nearly sky, sand dunes and sunshine as a house can be”). Their continuing fame is well deserved. Like Frank Lloyd Wright’s 880-square-foot Seth Peterson Cottage, another miniature masterpiece and the smallest of the “Usonian” houses that Wright designed for middle-class homeowners, the Walker Guest House is so compact and logically organized that to step inside feels almost as though you’re putting on a piece of clothing….

Today Rudolph, who died in 1997, is best remembered for his public buildings in the now-unfashionable “brutalist” style, many of which have either been torn down or are earmarked for demolition. But it was his Florida vacation homes that put him on the map, so much so that the Walker Guest House was the subject of an enthusiastic 1954 two-page spread in McCall’s (“This small summer house…is as nearly sky, sand dunes and sunshine as a house can be”). Their continuing fame is well deserved. Like Frank Lloyd Wright’s 880-square-foot Seth Peterson Cottage, another miniature masterpiece and the smallest of the “Usonian” houses that Wright designed for middle-class homeowners, the Walker Guest House is so compact and logically organized that to step inside feels almost as though you’re putting on a piece of clothing….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

“A Spider in the Sand,” a filmed interview with Elaine Walker, owner of the Walker Guest House:

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

An ArtsJournal Blog