“The advice of the elders to young men is very apt to be as unreal as a list of the hundred best books.”

“The advice of the elders to young men is very apt to be as unreal as a list of the hundred best books.”

Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., “The Path of the Law”

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

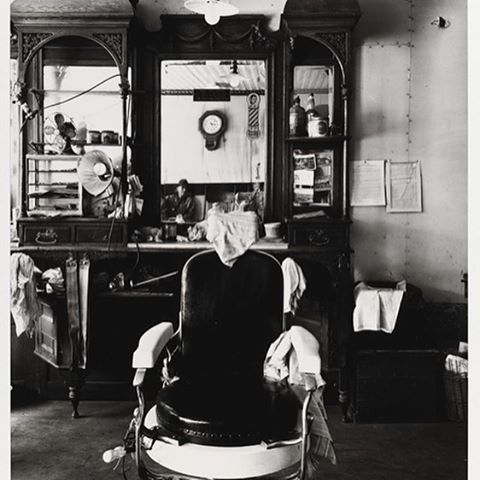

Back when I lived in a snug one-bedroom apartment not far from Central Park, I used to get my hair cut at Antonio’s, an unpretentious three-chair neighborhood barbershop with a Spanish-speaking staff and clientele. I loved going there, both because it was two blocks from my front door and because it reminded me of the similarly unpretentious place in Smalltown, U.S.A., where I got my hair cut as a boy, a one-chair shop owned and operated by a nice man named Willard Parks. It was Mr. Parks (as I always called him, even after I grew up and moved away from home) who shepherded me through the awkward age during which my father grudgingly allowed me to let the no-nonsense crewcut of my childhood grow into the nondescript, not-too-long mop of hair, formerly mousy brown and now mostly silver, that I’ve worn ever since.

Back when I lived in a snug one-bedroom apartment not far from Central Park, I used to get my hair cut at Antonio’s, an unpretentious three-chair neighborhood barbershop with a Spanish-speaking staff and clientele. I loved going there, both because it was two blocks from my front door and because it reminded me of the similarly unpretentious place in Smalltown, U.S.A., where I got my hair cut as a boy, a one-chair shop owned and operated by a nice man named Willard Parks. It was Mr. Parks (as I always called him, even after I grew up and moved away from home) who shepherded me through the awkward age during which my father grudgingly allowed me to let the no-nonsense crewcut of my childhood grow into the nondescript, not-too-long mop of hair, formerly mousy brown and now mostly silver, that I’ve worn ever since.

After Mrs. T and I got married, we moved to a bigger apartment at the northern end of Manhattan and simultaneously started spending much of our time at her place in rural Connecticut. It proved more convenient to get my hair cut there than here, so now I go to the place that she favors, a jumbo hair salon and day spa where I submit to the tonsorial ministrations of women half my age. I don’t mind going there, but it’s not even slightly my kind of place. Being an old-fashioned person at heart, I prefer to do business at old-fashioned shops, preferably ones that remind me in some way or other of the town where I grew up.

For this reason, I occasionally get my hair trimmed at G Studio, a tiny storefront salon close to our New York apartment that is, like Antonio’s, operated by Spanish-speaking people. That, however, is where the resemblance ends: G Studio is a place where women of a certain age do the hair and nails of other women of a certain age. Mrs. T, who calls it “the little-old-lady salon,” goes there to get her hair blown out whenever we’re seeing a Broadway show, and I go whenever I’m looking scruffier than usual (I’ve never given much thought to my personal appearance) and feel the urgent need to do something about it. You can usually get a haircut without an appointment so long as you’re not picky about who does the cutting, which suits me fine. I wouldn’t exactly say that Studio G is my kind of place, either: I grew up going to all-male barbershops, and while I prefer the company of women to men under virtually all circumstances, that preference can be trumped by the siren song of nostalgia. Nevertheless, Studio G is old-fashioned enough that I feel comfortable whenever I go there in search of a trim, as I did on Saturday morning.

One of the hairdressers waved me into her chair, and no sooner did I sit down than she asked, “Hey, how’s your nice lady? She not been here for three, four weeks. She O.K.?” I hadn’t counted on being recognized, much less tagged on the spot as Mrs. T’s spouse. That’s how you know you’ve settled into a neighborhood: you’re a regular. It also says a lot about Mrs. T. I’ve never known anyone who was quicker to strike up a friendly conversation with a stranger, or more reluctant to bring it to a close. I’m far too shy to be that outgoing, though I’ve taught myself how to convincingly simulate the motions of bonhomie with people whom I don’t know. With her, it comes naturally.

Getting my hair cut always reminds me of how easy it is for an introverted person to fall out of touch with the world. I’m not talking about the increasingly impermeable bubbles of class and tribe in which most of us live. This isn’t going to be one of those pieces in which an embubbled person blathers on about class attitudes of which he knows nothing after spending two minutes pretending to listen to a cab driver. I’m talking about the effects of chronic shyness on an aesthete who, in addition to being ill at ease with strangers, takes little or no interest in many of the great swathes of human experience that give people something to talk about other than the meaning of life. I know, for example, nothing of sports, have no children, and rarely watch series TV or go to pop-culture movies or read best-selling books. I can’t even cook (though I’ve been working on it). Ask me about Milton Avery or film noir and I’m all yours, but mention Spider-Man: Homecoming and I’m lost at sea.

Getting my hair cut always reminds me of how easy it is for an introverted person to fall out of touch with the world. I’m not talking about the increasingly impermeable bubbles of class and tribe in which most of us live. This isn’t going to be one of those pieces in which an embubbled person blathers on about class attitudes of which he knows nothing after spending two minutes pretending to listen to a cab driver. I’m talking about the effects of chronic shyness on an aesthete who, in addition to being ill at ease with strangers, takes little or no interest in many of the great swathes of human experience that give people something to talk about other than the meaning of life. I know, for example, nothing of sports, have no children, and rarely watch series TV or go to pop-culture movies or read best-selling books. I can’t even cook (though I’ve been working on it). Ask me about Milton Avery or film noir and I’m all yours, but mention Spider-Man: Homecoming and I’m lost at sea.

It’s not that I’m ill at ease with myself. I am, as I once described myself, a “regular-guy aesthete,” as happy with Sausage McMuffins as haute cuisine, and while I wish I were just a bit more on the regular side, I really do like the kind of guy I’m. But it’s also true that I’m simply not like most other people in most of the ways that matter, a fact that I figured out early on and which to this day has oddly distorting effects on my personality. As I once confessed in this space, I actually get squirmy when strangers in a restaurant ask me what I’m reading:

I think the origins of my discomfort must go all the way back to my small-town youth, when I was rarely to be seen without a book in hand. Even as a child, my reading habits were fairly advanced, and I got kidded mercilessly for toting around such triple-decker novels as Moby-Dick and Les Misérables. The teasing of my peers had an aggressive edge (“Hey, man, Teachout reads the encyclopedia!”), whereas my elders were merely puzzled, but the net result was to make me self-conscious whenever anyone asked what I was reading. Nearly four decades later, that question still makes me tighten up a bit, fully expecting to be razzed, and though it rarely happens nowadays, the resulting exchanges nonetheless tend to leave me feeling like a lifetime member of the awkward squad.

That’s why I enjoy getting my hair cut, even in new-fangled salons. A haircut is a controlled, script-driven social interaction that takes place in an setting where a shy person can enjoy the sensation of being around and eavesdropping on strangers without having to interact with them. As for the person who actually cuts your hair, it’s taken for granted that you can chat with her as much or as little as you like. So long as you’re properly courteous, no one will think the worse of you for choosing the latter over the former. And when the barbershop or salon in question is sufficiently old-fashioned to remind you of the world of your much-loved, much-missed youth, that makes the experience sweeter still.

I didn’t feel much like chatting on Saturday, so I settled into the chair, closed my eyes, and tuned in to the sounds around me. Michael Jackson was singing “Human Nature” on the radio as the little old ladies of Hudson Heights chattered aimlessly. I thought of the lines from James Agee’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” that Samuel Barber set so beautifully: They are not talking much, and the talk is quiet, of nothing in particular, of nothing at all. That’s the way old friends and family talk when they get together, and I found it soothing on Saturday. No, there’s no place like home, but there are places that can sometimes remind you of home so strongly that you might almost be there again. When you’re a middle-aged big-city exile who lives halfway across the country from the small town where you grew up, that’s a lot better than nothing.

I didn’t feel much like chatting on Saturday, so I settled into the chair, closed my eyes, and tuned in to the sounds around me. Michael Jackson was singing “Human Nature” on the radio as the little old ladies of Hudson Heights chattered aimlessly. I thought of the lines from James Agee’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” that Samuel Barber set so beautifully: They are not talking much, and the talk is quiet, of nothing in particular, of nothing at all. That’s the way old friends and family talk when they get together, and I found it soothing on Saturday. No, there’s no place like home, but there are places that can sometimes remind you of home so strongly that you might almost be there again. When you’re a middle-aged big-city exile who lives halfway across the country from the small town where you grew up, that’s a lot better than nothing.

When the hairdresser was finished, she said, “You tell your nice lady I say hello and come back soon.”

“I will,” I said. “I’ll tell her tonight.”

* * *

A scene from Barbershop, directed by Tim Story. The song is Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up”:

I wrote the “Masterpiece” column in Saturday’s Wall Street Journal. The subject is Louis Armstrong’s 1955 record of Kurt Weill’s “Mack the Knife.” Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

For all the enduring success of their other collaborations, Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill are both best remembered for “Die Dreigroschenoper” (“The Threepenny Opera”), their caustically witty 1928 adaptation of John Gay’s 1728 “Beggar’s Opera,” which portrayed low life in 18th-century London. But it was not until 1955 that the American public at large first heard any part of “The Threepenny Opera”—and it was Louis Armstrong, the most important figure in the history of jazz, who introduced them to it.

In September of that year, Armstrong and His All Stars recorded “Mack the Knife,” Marc Blitzstein’s English-language version of “Die Moritat von Mackie Messer,” a “murder ballad” about the vicious exploits of the show’s principal character that was the most popular number in “The Threepenny Opera.” Armstrong’s deliciously swinging cover version became a hit single, one of a handful of small-group jazz recordings ever to do so, and he would perform it the world over until he died in 1971.

In September of that year, Armstrong and His All Stars recorded “Mack the Knife,” Marc Blitzstein’s English-language version of “Die Moritat von Mackie Messer,” a “murder ballad” about the vicious exploits of the show’s principal character that was the most popular number in “The Threepenny Opera.” Armstrong’s deliciously swinging cover version became a hit single, one of a handful of small-group jazz recordings ever to do so, and he would perform it the world over until he died in 1971.

Armstrong was introduced to “Mack the Knife” by George Avakian, his producer at Columbia Records. Mr. Avakian, who was determined to put his beloved Satchmo back on the pop charts, had recently seen the 1954 off-Broadway revival of “The Threepenny Opera.” While the original 1933 Broadway production had closed after just 12 performances, this small-scale staging, newly translated by Blitzstein, the author of “The Cradle Will Rock,” became a sleeper hit, ultimately running for six years. Mr. Avakian came home certain that “Mack the Knife” had the makings of a hit single…

Armstrong found the song richly evocative of his New Orleans childhood, laughing out loud as he listened to the demo. “Oh, I’m going to love doing this!” he told Mr. Avakian. “I knew cats like this in New Orleans. Every one of them, they’d stick a knife into you without blinking an eye!”…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Louis Armstrong and the All Stars perform “Mack the Knife” on ABC’s Hollywood Palace in 1965:

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I review a pair of Massachusetts revivals, Lynn Nottage’s Intimate Apparel and Alan Ayckbourn’s Taking Steps. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Lynn Nottage’s “Intimate Apparel,” first performed in 2003, is now a regional-theater staple, partly because it calls for a modest set and a smallish cast of six but mostly because it’s one of the very best American plays of the past quarter-century. The tale of Esther (Nehassaiu deGannes), an illiterate turn-of-the-century black seamstress who suffers grievously when she falls in love with the wrong man, it unfolds in Daniela Varon’s Shakespeare & Company revival with an unadorned simplicity that reminded me of a silent movie when I saw “Intimate Apparel” off Broadway 13 years ago. I don’t mean to suggest that the dialogue is in any way lacking, for it is, as always with Ms. Nottage, plain-spoken and pungent (“He was too proper to like anything colored”). But the play’s dramatic gestures are so forthright that you scarcely need to attend closely to what the characters are saying in order to respond to the emotional import of their tragic situation….

Casting is crucial in a show like this, and Ms. deGannes, whose part was played in 2004 by Viola Davis, is fully as good as her celebrated predecessor. Ms. deGannes brought off the singular feat of making a fiercely positive impression as Cordelia in Chicago Shakespeare’s 2014 “King Lear,” and her performance this time around is identically distinguished. At first she comes across as mousy, but by play’s end you realize that her seeming shyness is a façade that only just conceals a boiling reservoir of ambition—and anger….

Casting is crucial in a show like this, and Ms. deGannes, whose part was played in 2004 by Viola Davis, is fully as good as her celebrated predecessor. Ms. deGannes brought off the singular feat of making a fiercely positive impression as Cordelia in Chicago Shakespeare’s 2014 “King Lear,” and her performance this time around is identically distinguished. At first she comes across as mousy, but by play’s end you realize that her seeming shyness is a façade that only just conceals a boiling reservoir of ambition—and anger….

Alan Ayckbourn’s plays, many of which combine frenzied farce with deep-dyed melancholy, are popular in England but much less well known over here. Could the problem be that audiences in this country prefer that funny plays be funny and serious plays serious? Whatever the reason, an Ayckbourn revival is always worth traveling to see, and Barrington Stage Company’s production of “Taking Steps,” which had a brief Broadway run in 1991 but doesn’t seem to have received any major American stagings since then, is a joyous romp from curtain to curtain.

“Taking Steps,” like “Bedroom Farce” and “The Norman Conquests” before it, is one of Mr. Ayckbourn’s scenically conceptual plays. The initiating premise is that the action takes place in a rundown three-story country house that is allegedly haunted and was once a Victorian brothel—except that there aren’t any stairs. Instead, the three floors are all on the same level, and the actors mime clambering up and down the steps that connect them….

“Taking Steps,” like “Bedroom Farce” and “The Norman Conquests” before it, is one of Mr. Ayckbourn’s scenically conceptual plays. The initiating premise is that the action takes place in a rundown three-story country house that is allegedly haunted and was once a Victorian brothel—except that there aren’t any stairs. Instead, the three floors are all on the same level, and the actors mime clambering up and down the steps that connect them….

“Taking Steps” was written to be performed in the round, and any attempt to mount it on a proscenium stage, as Barrington Stage is doing, must account for this inescapable fact. Enter Sam Buntrock, the director, whose solution to the problem, arrived at in collaboration with Jason Sherwood and David Weiner, respectively the set and lighting designers, is to interlock the three playing areas instead of placing them side by side on the stage, using lighting cues to signal where the characters are at any given moment, the same way it’s done in the round. You’ll have no trouble keeping up with their demented doings, and Mr. Buntrock is splendidly adept at the hair-trigger timing necessary to keep a farce in motion….

* * *

To read my review of Intimate Apparel, go here.

To read my review of Taking Steps, go here.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

An ArtsJournal Blog