Mrs. T and I went to Florida for the first time in 2009. We’ve returned each winter since then to see shows. This year, though, we’re staying home. Thereby hangs a tale that is both frightening and hopeful.

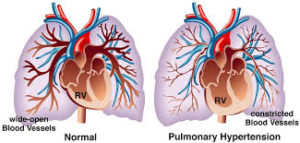

A couple of years before we first met, Mrs. T was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, a chronic illness about which I had occasion to write in today’s Wall Street Journal. It’s an extremely rare disease of the lungs and heart that develops slowly and is unusually hard to diagnose—so much so that Mrs. T almost certainly had it for several years before she, or anyone else, understood what was going wrong with her.

A couple of years before we first met, Mrs. T was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension, a chronic illness about which I had occasion to write in today’s Wall Street Journal. It’s an extremely rare disease of the lungs and heart that develops slowly and is unusually hard to diagnose—so much so that Mrs. T almost certainly had it for several years before she, or anyone else, understood what was going wrong with her.

Don’t be surprised if you’ve never heard of pulmonary hypertension. I’ve yet to meet anybody other than a doctor who’s heard of it, unless they’ve got it themselves or know someone who does. Part of the problem is that PH (as it’s known to those who have it) is an “invisible” illness. Were you to see Mrs. T sitting down, you wouldn’t guess that there was anything wrong with her. This is one of the reasons why she’s long been reluctant to talk about it, or to let me discuss it in public. Now she’s changed her mind. She feels, as do I, that it’s time for both of us to start being open about what we deal with every day.

Many people with “invisible” illnesses encourage their friends to read The Spoon Theory, an essay by Christine Miserandino in which she explains what it’s like to have a chronic illness. I commend it to your attention, as well as this article by another woman who suffers from PH:

If you try to walk alongside me, you may notice that I need to slow down, or may have to try and catch my breath while speaking. You might notice me gasping for air if we had to walk up a hill or some steps. People with PH are often out of breath by the time they reach the third step in a flight of stairs. I may look perfectly healthy, but I have a lung-heart disease. Those are two very vital organs that needed to do the most basic of tasks that are often taken for granted, such as going up the stairs, or bending down to tie your shoes.

PH gradually wreaks havoc on your stamina, enough so that Mrs. T, who was still able to lead a near-normal life when we met and for a few years afterward, is now quite frail and must use oxygen around the clock. The not-so-quiet purr of her oxygen concentrator has grown so familiar to me that I actually get nervous whenever I’m home alone and it’s turned off.

Pulmonary hypertension is incurable, and it’s also terminal if left untreated. Palliative therapies can help to relieve the symptoms, though only up to a point. To this end, Mrs. T takes a dozen pills each day and wears a medicine pump and an implanted venous catheter that deliver vasodilators to her lungs around the clock. The drugs that she takes, however, are in some ways as debilitating as the disease itself—she’s usually somewhat nauseated and almost always in pain, as if she were on chemotherapy—and over time they lose their therapeutic effect.

We are, needless to say, as grateful as it’s possible to be to the doctors who’ve kept Mrs. T alive this long. They were betting against the house. When we met, late in 2005, her life expectancy was two years. I found that out by looking up pulmonary hypertension on Wikipedia, which isn’t the best possible way to learn the likely lifespan of someone with whom you’ve just fallen in love. It didn’t matter—I knew I’d met the woman of my dreams and was determined to make the most of whatever time we’d have together—but it still scared the hell out of me. Fortunately for both of us, brand-new treatments for PH became available shortly thereafter, which is why she’s still around.

We are, needless to say, as grateful as it’s possible to be to the doctors who’ve kept Mrs. T alive this long. They were betting against the house. When we met, late in 2005, her life expectancy was two years. I found that out by looking up pulmonary hypertension on Wikipedia, which isn’t the best possible way to learn the likely lifespan of someone with whom you’ve just fallen in love. It didn’t matter—I knew I’d met the woman of my dreams and was determined to make the most of whatever time we’d have together—but it still scared the hell out of me. Fortunately for both of us, brand-new treatments for PH became available shortly thereafter, which is why she’s still around.

We’ve known all along, though, that a time was coming when the palliative measures that keep Mrs. T afloat would cease to be helpful. In preparation for that day, we entered the lung-transplant program at New York-Presbyterian Hospital in 2010. I say “we” because you can’t enter a transplant program alone: you must also have a spouse, domestic partner, or close friend who is prepared to make a firm, fully informed commitment to helping you get through the surgery and caring for you afterward. The good news is that a double lung transplant removes your diseased organs and gives you a fresh start. It is, to be sure, as drastic a procedure as it sounds, but once you enter the end stages of PH, it’s also the only alternative to…well, let’s call it the dark encounter.

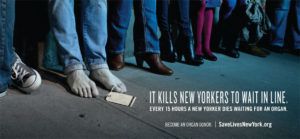

It’s been evident to both of us for the past year or so that Mrs. T would soon reach the point where there was no longer any alternative to a transplant. The catch is that there simply aren’t enough donor lungs to go around in the New York transplant region. To donate the organs of a loved one is the greatest gift you can give, but one that not nearly enough people do give. Every fifteen hours, someone in New York dies while waiting for a donor organ.

It’s been evident to both of us for the past year or so that Mrs. T would soon reach the point where there was no longer any alternative to a transplant. The catch is that there simply aren’t enough donor lungs to go around in the New York transplant region. To donate the organs of a loved one is the greatest gift you can give, but one that not nearly enough people do give. Every fifteen hours, someone in New York dies while waiting for a donor organ.

As this article explains, there’s a yawning gap between saying that you believe in organ donation and being willing to walk the walk:

Why don’t more people donate? It’s a touchy question, something non-donors aren’t necessarily keen to answer. But experts say there is a large disparity between the number of people who say that they support organ donation in theory and the number of people who actually register. In the U.K., for example, more than 90 percent of people say they support organ donation in opinion polls, but less than one-third are registered donors.

For this reason, Selim Arcasoy, the wonderful doctor at New York-Presbyterian who is in charge of Mrs. T’s care there, suggested to us earlier this year that we should consider simultaneously enrolling her in a second program located in a different transplant region where organs are less scarce. So we had her evaluated last month by Philadelphia’s Penn Transplant Institute, and Penn subsequently accepted her into its lung-transplant program.

For this reason, Selim Arcasoy, the wonderful doctor at New York-Presbyterian who is in charge of Mrs. T’s care there, suggested to us earlier this year that we should consider simultaneously enrolling her in a second program located in a different transplant region where organs are less scarce. So we had her evaluated last month by Philadelphia’s Penn Transplant Institute, and Penn subsequently accepted her into its lung-transplant program.

All of which brings us to the reason for this posting. If you need a transplant, the time will eventually come when you’re put on an active waiting list. Once that happens, you’re on call 24/7. When the call comes, you’re expected to go straight from wherever you are to the hospital, with no stops along the way. Very often it’s a false alarm—the organs, for example, may prove on closer inspection not to be suitable for transplant—but if it isn’t, you’ll be on the operating table a few hours later.

If you read this blog with any regularity, you know that Mrs. T and I have been profoundly happy throughout the decade we’ve spent together. Nevertheless, she is, as the saying goes, sick and tired of being sick and tired, which is why she’s ready to roll the dice and undergo a double lung transplant as soon as organs become available. Dr. Arcasoy and his colleagues think she’s ready, too, so New York-Presbyterian will be “listing” Mrs. T for transplant later this month. We expect Penn to follow suit shortly.

Both of us will soon be keeping our cellphones charged and on at all times, since there’s no telling when the call might come. It might be next Saturday at three in the morning, or six months from now. That’s the way it goes with transplants: you never know until the phone rings, though we’ve been told that you do tend more often than not to get called in the middle of the night.

Both of us will soon be keeping our cellphones charged and on at all times, since there’s no telling when the call might come. It might be next Saturday at three in the morning, or six months from now. That’s the way it goes with transplants: you never know until the phone rings, though we’ve been told that you do tend more often than not to get called in the middle of the night.

We’ve been through this before, sort of. It looked as though Mrs. T were going to be listed a couple of years ago, and we let ourselves get excited enough to tell our friends that the Great Day was coming. No such luck. It didn’t happen, and our disappointment was palpable. This time, though, it’s definitely the real right thing, not just at one transplant center but in two different cities at once.

Just in case you were wondering, I’m proud beyond belief to be the husband of and caregiver to so gallant a woman. It is a joy for me to make her life as easy as I possibly can, and there has never been anyone with whom I’ve loved staying home more than her. Donald Hall said it:

Nursing her I felt alive

in the animal moment,

scenting the predator.

Her death was the worst thing

that could happen,

and caring for her was best.

I hasten to add that the caregiving in our little family unit of two has never been a one-way affair! Mrs. T has given me at least as much pleasure and inspiration as I’ve tried to give her. I have no idea where she finds the strength to cope with the day-to-day demands of the illness that has slowly gnawed away her physical vitality, or how she manages to keep her spirits so improbably high, even on the increasingly frequent days of total exhaustion that those who suffer from PH refer to as “couch days.” Alas, she’s needed a steadily increasing amount of care in recent years, and will need still more in the weeks and months to come, not just from me but from our family and friends. We have no doubt that they will rise to the occasion, just as I’ve tried to do so to the very best of my ability.

I hasten to add that the caregiving in our little family unit of two has never been a one-way affair! Mrs. T has given me at least as much pleasure and inspiration as I’ve tried to give her. I have no idea where she finds the strength to cope with the day-to-day demands of the illness that has slowly gnawed away her physical vitality, or how she manages to keep her spirits so improbably high, even on the increasingly frequent days of total exhaustion that those who suffer from PH refer to as “couch days.” Alas, she’s needed a steadily increasing amount of care in recent years, and will need still more in the weeks and months to come, not just from me but from our family and friends. We have no doubt that they will rise to the occasion, just as I’ve tried to do so to the very best of my ability.

Anyway, that’s why we’re not going to Florida in January. Love it though we do, it’s too far away from New York and Philadelphia for us to respond in a timely way to the Big Call, and Mrs. T’s lungs and heart are no longer up to the stress of air travel. We tried taking a train two years ago, but it didn’t work out very well. So the sunshine will have to wait.

I should add that I’ll still be flying down to West Palm Beach next Monday to rehearse Billy and Me, my new play. I agreed to do so long before we had any idea that Mrs. T would be listed in November, and she’s made it clear that she expects me to honor my promise. While I’m gone, she’ll be watched over by her family in Connecticut. They’ll stand ready to rush her to the hospital if need be, at which time I’ll catch the first thing smoking. Otherwise, I’ll return to her side as soon as the curtain goes up, putting my traveling shoes in the closet for the duration.

We both know what we’re getting into. Anyone who’s been in a transplant program is left in no doubt about what is to come. Mrs. T’s post-transplant life will be upended in countless ways both large (she’ll be under close medical supervision for the rest of her life) and small (no more raw oysters ever again!). We know, too, that no transplant—to put it very, very mildly—is a sure thing. But if we get lucky and do just what we’re supposed to do, she’ll also be able to turn off her oxygen concentrator for good and give it to someone who can’t afford one.

We both know what we’re getting into. Anyone who’s been in a transplant program is left in no doubt about what is to come. Mrs. T’s post-transplant life will be upended in countless ways both large (she’ll be under close medical supervision for the rest of her life) and small (no more raw oysters ever again!). We know, too, that no transplant—to put it very, very mildly—is a sure thing. But if we get lucky and do just what we’re supposed to do, she’ll also be able to turn off her oxygen concentrator for good and give it to someone who can’t afford one.

And after that? In the short run, she’ll gladly settle for being able to walk up a flight of stairs without having to gasp for breath. Beyond that, we’re drawing up a list of Things to Do After the Transplant. Foremost among them is to go back to Florida and spend hours each day walking up and down the shelly beaches of Sanibel Island, our favorite place in the world. It’s been a long time since Mrs. T has had enough strength to take such walks with me. We’re ready to begin again.

One last thing: if you haven’t signed up to be an organ donor, please do so now, and encourage your friends to do likewise. The life you save could be that of the woman I love.

* * *

Mabel Mercer and Buddy Barnes perform “The Best Is Yet to Come,” by Cy Coleman and Carolyn Leigh, at New York’s Town Hall in 1969:

All this came to mind when a copy of “The Encore: A Memoir in Three Acts,” a newly published memoir by Charity Tillemann-Dick, turned up in my mailbox the other day. Ms. Tillemann-Dick is a coloratura soprano who has continued to perform after undergoing two double lung transplants, an achievement that is unique in the history of singing. I vaguely recalled having read about her horrific experiences, but knew nothing of the details. Now I know all about them, and I find myself in awe of her, not just because of her indomitable determination but because it turns out that in addition to being an excellent singer, Ms. Tillemann-Dick is also a very fine writer. “The Encore” is one of the best books I’ve ever read about the effects of chronic illness on the human spirit. Most of us, I suspect, like to think that we’d rise to a difficult occasion if forced to do so, but rarely are we put to the test. Ms. Tillemann-Dick was, and she faced it with a courage that I can scarcely begin to fathom….

All this came to mind when a copy of “The Encore: A Memoir in Three Acts,” a newly published memoir by Charity Tillemann-Dick, turned up in my mailbox the other day. Ms. Tillemann-Dick is a coloratura soprano who has continued to perform after undergoing two double lung transplants, an achievement that is unique in the history of singing. I vaguely recalled having read about her horrific experiences, but knew nothing of the details. Now I know all about them, and I find myself in awe of her, not just because of her indomitable determination but because it turns out that in addition to being an excellent singer, Ms. Tillemann-Dick is also a very fine writer. “The Encore” is one of the best books I’ve ever read about the effects of chronic illness on the human spirit. Most of us, I suspect, like to think that we’d rise to a difficult occasion if forced to do so, but rarely are we put to the test. Ms. Tillemann-Dick was, and she faced it with a courage that I can scarcely begin to fathom….