Mrs. T and I ate fresh corn on the cob and tomatoes for dinner for three nights in a row last week. My long-lost childhood self would have boggled at the thought of so unswerving a diet: I was moderately vegetable-aversive and also had a medium-sized tomato problem. It wasn’t until I met Mrs. T and started summering in rural Connecticut that I discovered the joys of dining on fresh vegetables bought at farm stands close to home.

Mrs. T and I ate fresh corn on the cob and tomatoes for dinner for three nights in a row last week. My long-lost childhood self would have boggled at the thought of so unswerving a diet: I was moderately vegetable-aversive and also had a medium-sized tomato problem. It wasn’t until I met Mrs. T and started summering in rural Connecticut that I discovered the joys of dining on fresh vegetables bought at farm stands close to home.

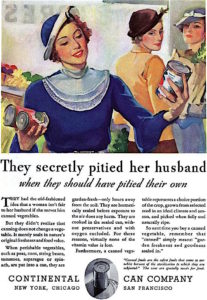

I suspect this state of affairs had not a little to do with the fact that my mother, who grew up during the Great Depression, never quite got over the miracle of canned vegetables. While my family must have eaten fresh corn on the cob at one time or another, I can’t remember our doing so. Most of the corn I ate back then—always with extreme reluctance—was spooned out of a dish. I’d never even heard the phrase “farm-to-table restaurant” until Mrs. T introduced me to it, nor did I have the slightest notion of what a resplendent pleasure it is to eat vegetables that are picked and purchased the same day they end up on your plate.

Mrs. T favors simple food, and there’s nothing she likes better than corn and tomatoes, which we buy at a stand located ten minutes or so from our front door. At first she served them as part of a varied rotation of dishes, but in time she got around to broaching the possibility that we might want to consider eating them more often in season, which led in due course to last week’s farmstand orgy.

Mrs. T favors simple food, and there’s nothing she likes better than corn and tomatoes, which we buy at a stand located ten minutes or so from our front door. At first she served them as part of a varied rotation of dishes, but in time she got around to broaching the possibility that we might want to consider eating them more often in season, which led in due course to last week’s farmstand orgy.

As I sat on the front porch husking corn late one afternoon, I remembered a passage from Rex Stout’s Might as Well Be Dead in which Archie Goodwin, Nero Wolfe’s trusty assistant, complains to Fritz Brenner, Wolfe’s personal chef, about the frequency with which shad roe is served each spring in the old brownstone at 454 West 35th Street:

“Hey,” I protested, “we had shad roe for lunch! Again for dinner?”

“My dear Archie.” He was superior, to me, only about food. “They were merely sauté, with a simple little sauce, only chives and chervil. These will be en casserole, with anchovy butter made by me. The sheets of larding will be rubbed with five herbs. With the cream to cover will be an onion and three other herbs, to be removed before serving. The roe season is short, and Mr. Wolfe could enjoy it three times a day. You can go to Al’s place on Tenth Avenue and enjoy a ham on rye with coleslaw.” He shuddered.

The season for corn and tomatoes is almost as short, and while I’m not absolutely sure I’d care to eat them three times a day, I’d certainly consider it.

Such summer feasts, however, are not without an accompanying touch of autumnal melancholy. For those who, like Mrs. T and I, have crossed the sixtieth meridian, it’s hard not to wonder come October how many more seasons remain for us to feast on the fruits of the field. Indeed, I found myself thinking of these oft-quoted lines by A.H. Housman as Mrs. T set yet another heaping plate in front of me:

Such summer feasts, however, are not without an accompanying touch of autumnal melancholy. For those who, like Mrs. T and I, have crossed the sixtieth meridian, it’s hard not to wonder come October how many more seasons remain for us to feast on the fruits of the field. Indeed, I found myself thinking of these oft-quoted lines by A.H. Housman as Mrs. T set yet another heaping plate in front of me:

Now, of my threescore years and ten,

Twenty will not come again,

And take from seventy springs a score,

It only leaves me fifty more.

And since to look at things in bloom

Fifty springs are little room,

About the woodlands I will go

To see the cherry hung with snow.

In other words, memento mori! Yet there are many possible responses to that dark imperative, not all of them drably penitential. We have it on good authority that it is man’s part to rejoice in the fruits of the earth and the fullness thereof, which strikes me as an impeccable reason to eat all the fresh corn and tomatoes that are going for as long as is humanly possible.

I’m no farmer, but I do know from experience that the corn in northeast Connecticut won’t be as good this week, and come next week it might not even be worth husking. Be that as it may, I expect that Mrs. T and I will be heading to the Red Barn Creamery later today to see what’s in the bin. If it looks good, we’ll bring some home, and if not…well, we’ll eat something else tonight. Robert Frost said it: nothing gold can stay.

I’m no farmer, but I do know from experience that the corn in northeast Connecticut won’t be as good this week, and come next week it might not even be worth husking. Be that as it may, I expect that Mrs. T and I will be heading to the Red Barn Creamery later today to see what’s in the bin. If it looks good, we’ll bring some home, and if not…well, we’ll eat something else tonight. Robert Frost said it: nothing gold can stay.

* * *

Bryn Terfel and Malcolm Martineau perform “Loveliest of trees,” George Butterworth’s setting of A.E. Housman’s poem: