In my latest Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I sound off on the Berkshire Museum’s planned sale of important works from its permanent collection. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

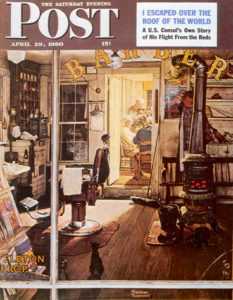

Norman Rockwell’s greatest painting is being hijacked—by the museum that owns it.

Norman Rockwell’s greatest painting is being hijacked—by the museum that owns it.

“Shuffleton’s Barbershop” is a 1950 portrait of three amateur musicians that Rockwell gave to the Berkshire Museum, located in Pittsfield, Mass., not far from Stockbridge, his home. Widely known and loved, the painting is even admired by critics who sneer at the rest of his homey oeuvre. Nevertheless, the Berkshire Museum is putting it on the block, along with a second Rockwell painting and 38 other works by such major artists as Albert Bierstadt, Alexander Calder and Augustus Saint-Gaudens.

The reason? Van Shields, director of the Berkshire Museum, wants to “reboot” (his word) the institution, transforming it into a museum of science, history and the arts full of up-to-the-minute interactive technology. The price tag is $60 million—$20 million to renovate the museum’s 1903 building and the rest for a much-needed endowment. The art is being sold to pay the tab because, in the bland language of the museum’s press release, it is “deemed no longer essential to the Museum’s new interdisciplinary programs.”…

Because art museums are public institutions whose collections are held in trust, strict rules govern the “deaccessioning” (selling) of works from their collections. Rule No. 1 is that art can be sold only to acquire more art, and the Association of Art Museum Directors further stipulates that proceeds may never be used “as operating funds, to build a general endowment, or for any other expenses.” Not surprisingly, the AAMD and the American Alliance of Museums issued a joint statement calling the proposed sale “an irredeemable loss for the present and for generations to come.”

The Berkshire Museum, however, is not an art museum per se. A collection of 40,000-odd objects ranging from Hudson River School paintings to mummies and stuffed birds, it’s reminiscent of the New England “historical societies” that John P. Marquand described in a novel as charmingly eccentric muddles of “aboriginal arrowheads, muskets, candle molds, foot warmers, pine dressers, Chippendale sideboards, Lowestoft, pewter, and whales’ teeth and four-poster beds.” Indeed, its eccentricity was part of its charm.

The Berkshire Museum, however, is not an art museum per se. A collection of 40,000-odd objects ranging from Hudson River School paintings to mummies and stuffed birds, it’s reminiscent of the New England “historical societies” that John P. Marquand described in a novel as charmingly eccentric muddles of “aboriginal arrowheads, muskets, candle molds, foot warmers, pine dressers, Chippendale sideboards, Lowestoft, pewter, and whales’ teeth and four-poster beds.” Indeed, its eccentricity was part of its charm.

But can such an old-fashioned curiosity shop hold its own amid newer outposts like Mass MoCA and expanded, revitalized institutions like the Clark Art Institute—not to mention the Rockwell Museum itself? Probably not. In any case, the Berkshire Museum has already evolved into something closer to a children’s museum, a place where no one goes to see art….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.