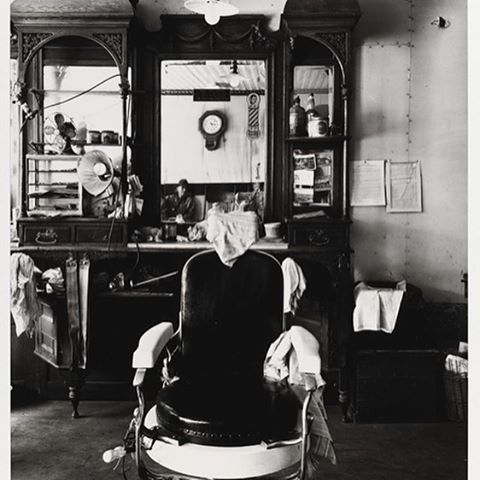

Back when I lived in a snug one-bedroom apartment not far from Central Park, I used to get my hair cut at Antonio’s, an unpretentious three-chair neighborhood barbershop with a Spanish-speaking staff and clientele. I loved going there, both because it was two blocks from my front door and because it reminded me of the similarly unpretentious place in Smalltown, U.S.A., where I got my hair cut as a boy, a one-chair shop owned and operated by a nice man named Willard Parks. It was Mr. Parks (as I always called him, even after I grew up and moved away from home) who shepherded me through the awkward age during which my father grudgingly allowed me to let the no-nonsense crewcut of my childhood grow into the nondescript, not-too-long mop of hair, formerly mousy brown and now mostly silver, that I’ve worn ever since.

Back when I lived in a snug one-bedroom apartment not far from Central Park, I used to get my hair cut at Antonio’s, an unpretentious three-chair neighborhood barbershop with a Spanish-speaking staff and clientele. I loved going there, both because it was two blocks from my front door and because it reminded me of the similarly unpretentious place in Smalltown, U.S.A., where I got my hair cut as a boy, a one-chair shop owned and operated by a nice man named Willard Parks. It was Mr. Parks (as I always called him, even after I grew up and moved away from home) who shepherded me through the awkward age during which my father grudgingly allowed me to let the no-nonsense crewcut of my childhood grow into the nondescript, not-too-long mop of hair, formerly mousy brown and now mostly silver, that I’ve worn ever since.

After Mrs. T and I got married, we moved to a bigger apartment at the northern end of Manhattan and simultaneously started spending much of our time at her place in rural Connecticut. It proved more convenient to get my hair cut there than here, so now I go to the place that she favors, a jumbo hair salon and day spa where I submit to the tonsorial ministrations of women half my age. I don’t mind going there, but it’s not even slightly my kind of place. Being an old-fashioned person at heart, I prefer to do business at old-fashioned shops, preferably ones that remind me in some way or other of the town where I grew up.

For this reason, I occasionally get my hair trimmed at G Studio, a tiny storefront salon close to our New York apartment that is, like Antonio’s, operated by Spanish-speaking people. That, however, is where the resemblance ends: G Studio is a place where women of a certain age do the hair and nails of other women of a certain age. Mrs. T, who calls it “the little-old-lady salon,” goes there to get her hair blown out whenever we’re seeing a Broadway show, and I go whenever I’m looking scruffier than usual (I’ve never given much thought to my personal appearance) and feel the urgent need to do something about it. You can usually get a haircut without an appointment so long as you’re not picky about who does the cutting, which suits me fine. I wouldn’t exactly say that Studio G is my kind of place, either: I grew up going to all-male barbershops, and while I prefer the company of women to men under virtually all circumstances, that preference can be trumped by the siren song of nostalgia. Nevertheless, Studio G is old-fashioned enough that I feel comfortable whenever I go there in search of a trim, as I did on Saturday morning.

One of the hairdressers waved me into her chair, and no sooner did I sit down than she asked, “Hey, how’s your nice lady? She not been here for three, four weeks. She O.K.?” I hadn’t counted on being recognized, much less tagged on the spot as Mrs. T’s spouse. That’s how you know you’ve settled into a neighborhood: you’re a regular. It also says a lot about Mrs. T. I’ve never known anyone who was quicker to strike up a friendly conversation with a stranger, or more reluctant to bring it to a close. I’m far too shy to be that outgoing, though I’ve taught myself how to convincingly simulate the motions of bonhomie with people whom I don’t know. With her, it comes naturally.

Getting my hair cut always reminds me of how easy it is for an introverted person to fall out of touch with the world. I’m not talking about the increasingly impermeable bubbles of class and tribe in which most of us live. This isn’t going to be one of those pieces in which an embubbled person blathers on about class attitudes of which he knows nothing after spending two minutes pretending to listen to a cab driver. I’m talking about the effects of chronic shyness on an aesthete who, in addition to being ill at ease with strangers, takes little or no interest in many of the great swathes of human experience that give people something to talk about other than the meaning of life. I know, for example, nothing of sports, have no children, and rarely watch series TV or go to pop-culture movies or read best-selling books. I can’t even cook (though I’ve been working on it). Ask me about Milton Avery or film noir and I’m all yours, but mention Spider-Man: Homecoming and I’m lost at sea.

Getting my hair cut always reminds me of how easy it is for an introverted person to fall out of touch with the world. I’m not talking about the increasingly impermeable bubbles of class and tribe in which most of us live. This isn’t going to be one of those pieces in which an embubbled person blathers on about class attitudes of which he knows nothing after spending two minutes pretending to listen to a cab driver. I’m talking about the effects of chronic shyness on an aesthete who, in addition to being ill at ease with strangers, takes little or no interest in many of the great swathes of human experience that give people something to talk about other than the meaning of life. I know, for example, nothing of sports, have no children, and rarely watch series TV or go to pop-culture movies or read best-selling books. I can’t even cook (though I’ve been working on it). Ask me about Milton Avery or film noir and I’m all yours, but mention Spider-Man: Homecoming and I’m lost at sea.

It’s not that I’m ill at ease with myself. I am, as I once described myself, a “regular-guy aesthete,” as happy with Sausage McMuffins as haute cuisine, and while I wish I were just a bit more on the regular side, I really do like the kind of guy I’m. But it’s also true that I’m simply not like most other people in most of the ways that matter, a fact that I figured out early on and which to this day has oddly distorting effects on my personality. As I once confessed in this space, I actually get squirmy when strangers in a restaurant ask me what I’m reading:

I think the origins of my discomfort must go all the way back to my small-town youth, when I was rarely to be seen without a book in hand. Even as a child, my reading habits were fairly advanced, and I got kidded mercilessly for toting around such triple-decker novels as Moby-Dick and Les Misérables. The teasing of my peers had an aggressive edge (“Hey, man, Teachout reads the encyclopedia!”), whereas my elders were merely puzzled, but the net result was to make me self-conscious whenever anyone asked what I was reading. Nearly four decades later, that question still makes me tighten up a bit, fully expecting to be razzed, and though it rarely happens nowadays, the resulting exchanges nonetheless tend to leave me feeling like a lifetime member of the awkward squad.

That’s why I enjoy getting my hair cut, even in new-fangled salons. A haircut is a controlled, script-driven social interaction that takes place in an setting where a shy person can enjoy the sensation of being around and eavesdropping on strangers without having to interact with them. As for the person who actually cuts your hair, it’s taken for granted that you can chat with her as much or as little as you like. So long as you’re properly courteous, no one will think the worse of you for choosing the latter over the former. And when the barbershop or salon in question is sufficiently old-fashioned to remind you of the world of your much-loved, much-missed youth, that makes the experience sweeter still.

I didn’t feel much like chatting on Saturday, so I settled into the chair, closed my eyes, and tuned in to the sounds around me. Michael Jackson was singing “Human Nature” on the radio as the little old ladies of Hudson Heights chattered aimlessly. I thought of the lines from James Agee’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” that Samuel Barber set so beautifully: They are not talking much, and the talk is quiet, of nothing in particular, of nothing at all. That’s the way old friends and family talk when they get together, and I found it soothing on Saturday. No, there’s no place like home, but there are places that can sometimes remind you of home so strongly that you might almost be there again. When you’re a middle-aged big-city exile who lives halfway across the country from the small town where you grew up, that’s a lot better than nothing.

I didn’t feel much like chatting on Saturday, so I settled into the chair, closed my eyes, and tuned in to the sounds around me. Michael Jackson was singing “Human Nature” on the radio as the little old ladies of Hudson Heights chattered aimlessly. I thought of the lines from James Agee’s “Knoxville: Summer of 1915” that Samuel Barber set so beautifully: They are not talking much, and the talk is quiet, of nothing in particular, of nothing at all. That’s the way old friends and family talk when they get together, and I found it soothing on Saturday. No, there’s no place like home, but there are places that can sometimes remind you of home so strongly that you might almost be there again. When you’re a middle-aged big-city exile who lives halfway across the country from the small town where you grew up, that’s a lot better than nothing.

When the hairdresser was finished, she said, “You tell your nice lady I say hello and come back soon.”

“I will,” I said. “I’ll tell her tonight.”

* * *

A scene from Barbershop, directed by Tim Story. The song is Marvin Gaye’s “Got to Give It Up”:

In September of that year, Armstrong and His All Stars recorded “Mack the Knife,” Marc Blitzstein’s English-language version of “Die Moritat von Mackie Messer,” a “murder ballad” about the vicious exploits of the show’s principal character that was the most popular number in “The Threepenny Opera.” Armstrong’s deliciously swinging cover version became a hit single, one of a handful of small-group jazz recordings ever to do so, and he would perform it the world over until he died in 1971.

In September of that year, Armstrong and His All Stars recorded “Mack the Knife,” Marc Blitzstein’s English-language version of “Die Moritat von Mackie Messer,” a “murder ballad” about the vicious exploits of the show’s principal character that was the most popular number in “The Threepenny Opera.” Armstrong’s deliciously swinging cover version became a hit single, one of a handful of small-group jazz recordings ever to do so, and he would perform it the world over until he died in 1971.