I take music for granted—not because I don’t love it passionately, but because it has always been as much a part of my life as the air around me. To be sure, there have been times when I paid less attention to music, but sooner or later it has taken hold of me again. It is my second language, one learned in childhood, meaning that I “speak” it without an accent and as easily and naturally as I speak English. To come at it from the other direction, I experience a piece of instrumental music in much the same way that I experience a short story or an essay: it talks to me.

I take music for granted—not because I don’t love it passionately, but because it has always been as much a part of my life as the air around me. To be sure, there have been times when I paid less attention to music, but sooner or later it has taken hold of me again. It is my second language, one learned in childhood, meaning that I “speak” it without an accent and as easily and naturally as I speak English. To come at it from the other direction, I experience a piece of instrumental music in much the same way that I experience a short story or an essay: it talks to me.

I remember being overwhelmed by my first encounter with something that Felix Mendelssohn said in an 1842 letter to a friend: “The thoughts which are expressed to me by music that I love are not too indefinite to be put into words, but on the contrary, too definite. ” I also remember reading the following passage in a biography of Donald Francis Tovey and thinking, I know just what he meant:

I have (this sounds like fantastic nonsense, but it isn’t) frequently caught myself positively solving some problem (of a more or less philosophical nature) in, say, the key of A minor, where I had utterly failed to reason it out in words.

If music has this strong an effect on you, then there will be times when you feel an overpowering, almost physical urge to listen to a specific piece of it. Such a feeling came over me last night: I felt that if I couldn’t listen to the first movement of Charles Ives’ Third Symphony right away, I would be reduced to abject despair. Therein lies the supreme spiritual utility of the digital technology that has brought about what is without question the most radical transformation of daily life to take place in my lifetime: I screwed in my earbuds and clicked a few keys on my MacBook, and all at once my head was full of Ives.

If music has this strong an effect on you, then there will be times when you feel an overpowering, almost physical urge to listen to a specific piece of it. Such a feeling came over me last night: I felt that if I couldn’t listen to the first movement of Charles Ives’ Third Symphony right away, I would be reduced to abject despair. Therein lies the supreme spiritual utility of the digital technology that has brought about what is without question the most radical transformation of daily life to take place in my lifetime: I screwed in my earbuds and clicked a few keys on my MacBook, and all at once my head was full of Ives.

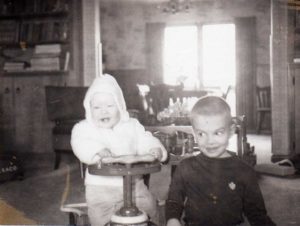

Why, though, was it this particular piece that I craved? I’m sure it was because I’d spent an hour talking to my brother on the phone on Tuesday night. A year has gone by since I saw David, and it’s been nearly two years to the day since my last visit to the small town in southeast Missouri where we grew up and where he still lives. Having lived in New York for thirty years, I can’t pretend to be anything other than a city dweller now, but I’m still a small-town boy at heart, and Ives’ Third Symphony, whose subtitle is “The Camp Meeting” and whose first movement is called “Old Folks Gatherin’,” overflows with the hymn tunes and homespun harmonies of Ives’ youth, which I, too, heard in church on Sunday mornings back in Smalltown, U.S.A. No sooner did I start listening to it than I was swept back in time, and when the music ended, I felt serene and secure, more so than I’ve felt for quite some time.

Not surprisingly, listening to “Old Folks Gatherin’” also made me long to see my brother. Alas, we won’t be together again until the first week in December, when he and his wife will be in West Palm Beach for the premiere of my new play. But we are always together in my heart, and that’ll have to do for now.

Not surprisingly, listening to “Old Folks Gatherin’” also made me long to see my brother. Alas, we won’t be together again until the first week in December, when he and his wife will be in West Palm Beach for the premiere of my new play. But we are always together in my heart, and that’ll have to do for now.

As I typed that last sentence, I found myself thinking of a sentence uttered by Abraham Lincoln a century and a half ago: “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” So far as I know, Lincoln didn’t much care for music, classical or otherwise, but anyone capable of penning a phrase like “mystic chords of memory” must surely have had some inkling of its ineffable power. Music is for me what the madeleine was for Proust: it opens the door to memory. Last night its mystic chords also bridged the thousand-mile gap between New York City and Smalltown, U.S.A., and put my beloved brother in the room with me for a few precious minutes. Of such little blessings is the life of a music lover made.

* * *

Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic perform Charles Ives’ Third Symphony: