Mrs. T and I love the art of Milton Avery and are the proud owners of handsome impressions of two of his most striking prints, a 1948 drypoint and a 1963 lithograph. For some time now we’ve also been longing to own a copy of one of Avery’s twenty-one hand-printed color woodcuts, a medium that he used with particular charm and imagination and to which he devoted a significant part of his dwindling physical energies in his later years, after a heart attack made it harder for him to paint on a large scale.

Mrs. T and I love the art of Milton Avery and are the proud owners of handsome impressions of two of his most striking prints, a 1948 drypoint and a 1963 lithograph. For some time now we’ve also been longing to own a copy of one of Avery’s twenty-one hand-printed color woodcuts, a medium that he used with particular charm and imagination and to which he devoted a significant part of his dwindling physical energies in his later years, after a heart attack made it harder for him to paint on a large scale.

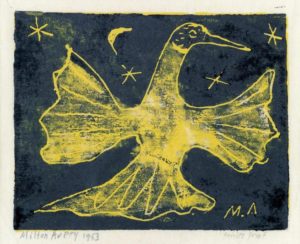

Mrs. T has a special liking for Dawn, the first of Avery’s woodcuts, a fanciful, almost childlike 1952 study of a flying seabird that Avery printed in two editions, one in yellow and black ink and one in black only. A very fine artist’s proof of the yellow-and-black 1953 edition of “Dawn” came up for auction in Manhattan a couple of months ago, and we decided to bid for it, not expecting to have any luck. To our amazement and delight, we placed the high bid, and now it is ours.

Alan Fern wrote well about Avery’s printmaking technique in his “technical note” to Milton Avery: Prints 1933-1955, the standard catalogue of Avery’s prints:

Alan Fern wrote well about Avery’s printmaking technique in his “technical note” to Milton Avery: Prints 1933-1955, the standard catalogue of Avery’s prints:

Avery preferred working in the most direct media of printing: drypoint and woodcut. In these, the actions of hand and tool are translated directly into a visible image, with no chemical intervention (as in etching) or elaborate preparation (as in lithography) before a proof can be taken. This was partly because his health was not always equal to the labor of printing, and partly because the process of printing identical impressions scarcely interested him, once the image had been created. In contrast, the woodblocks had to be printed individually, and he rejoiced in the subtle differences in value and color that could be introduced in the printing process….

All of the woodblocks were printed by rubbing, not in a press, and this enabled the artist to vary the background tone of each impression as he printed….To a great extent, each woodblock print is an individual experience; it is rare to find two of Avery’s woodcuts that are exactly the same, and it would be exceedingly difficult to make prints from the blocks today that would reflect Avery’s intention with any accuracy.

This homely, one-of-a-kind quality is an important part of what makes Avery’s woodcuts so appealing. In addition, the necessary simplifications of printmaking were very much in tune with his growing inclination to pare his work down to the bare essentials (as was also the case with Fairfield Porter, another of my favorite painters and a printmaker of like distinction).

This homely, one-of-a-kind quality is an important part of what makes Avery’s woodcuts so appealing. In addition, the necessary simplifications of printmaking were very much in tune with his growing inclination to pare his work down to the bare essentials (as was also the case with Fairfield Porter, another of my favorite painters and a printmaker of like distinction).

Hilton Kramer described this tendency with characteristic astuteness when he wrote about Avery’s late work in a 1982 essay:

The late Avery looks like the quintessential Avery to this observer. There is a lyric intensity in the landscape and seascape images unlike anything else in the art of our time. As in late Turner and late Cézanne, many of these images are characterized by an awesome concision. The canvas is divided into fewer and fewer formal components, and yet each strikes the eye with a compelling eloquence.

In its quieter way, “Dawn” partakes of this same eloquence and spare, pared-down simplicity.

Because Mrs. T loves it so much, we’ve decided to hang “Dawn” not in our New York apartment, where we keep the bulk of our collection, but in the farmhouse in rural Connecticut where she spends most of her time. Whenever I’m in New York or reviewing shows elsewhere in America, I’ll imagine her looking at it with pleasure, and smile at the thought.

UPDATE: I brought “Dawn” to our New York apartment after Mrs. T became too sick to continue living in Connecticut. It now hangs in the hall outside her bedroom.