“In universities and intellectual circles, academics can guarantee themselves popularity—or, which is just as satisfying, unpopularity—by being opinionated rather than by being learned.”

“In universities and intellectual circles, academics can guarantee themselves popularity—or, which is just as satisfying, unpopularity—by being opinionated rather than by being learned.”

A.N. Wilson (quoted in The Guardian, September 30, 1989)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column, I make a modest proposal that could transform American theater. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

What do Lucas Hnath, Lynn Nottage, J.T. Rogers and Paula Vogel have in common? If you recognize them as the authors of “A Doll’s House, Part 2,” “Sweat,” “Oslo” and “Indecent,” which received this year’s best-play Tony Award nominations, it’s a safe bet that you’re a serious theater buff. If, on the other hand, none of their names are familiar to you…well, I’m not surprised. Fifty years ago, the best-play nominees were Edward Albee’s “A Delicate Balance,” Frank Marcus’ “The Killing of Sister George,” Harold Pinter’s “The Homecoming” and Peter Shaffer’s “Black Comedy.” The average educated American would not only have heard of all four plays, but would likely have recognized the names of their authors. Today, by contrast, most people don’t know much about Broadway plays, much less the men and women who write them.

Why not? Because American theater no longer has what I call a “fame mechanism.” A half-century ago, Broadway was regularly covered by weekly newsmagazines like Time, Life and Newsweek, and it also figured prominently on such network TV series as “The Ed Sullivan Show,” “The Tonight Show” and “What’s My Line?” I saw Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,” my first Broadway play, on CBS—in prime time!

Why not? Because American theater no longer has what I call a “fame mechanism.” A half-century ago, Broadway was regularly covered by weekly newsmagazines like Time, Life and Newsweek, and it also figured prominently on such network TV series as “The Ed Sullivan Show,” “The Tonight Show” and “What’s My Line?” I saw Arthur Miller’s “Death of a Salesman,” my first Broadway play, on CBS—in prime time!

Theater’s “fame mechanism” broke down, however, as the old-time legacy media started to lose their dominant place in American culture. At the same time, live theater became geographically decentralized: “A Doll’s House, Part 2” was first performed by California’s South Coast Repertory, “Sweat” by the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, “Oslo” by Lincoln Center Theater at its off-Broadway house and “Indecent” by the Yale Repertory Theatre. That these plays were subsequently produced on Broadway ensures that they’ll have an afterlife. But what does it say about the state of American theater that dozens of other plays of comparable quality receive regional premieres every season without ever reaching Broadway? Is there another way to spread the word about such plays, as well as the outstanding companies that stage them?…

What if six top-tier regional theaters, backed by a foundation or two, were to join forces and start a national consortium that taped well-produced versions of live performances of a half-dozen plays—three new shows, three revivals—each season, then made them universally available for free? They could then be shown on local public-TV stations, or disseminated via more up-to-date methods like movie-theater simulcasts or Netflix-style streaming video….

In addition to publicizing its six member companies, my hypothetical Regional Theater Broadcast Consortium would be good for American theater as a whole. A telecast of a play, after all, is not merely a piece of entertainment, but an advertisement for live theater in general. It introduces everyone who watches it to another entertainment option—getting off your couch and into the nearest theate….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Lee J. Cobb stars in a TV version of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, directed by Alex Segal and originally telecast by CBS on May 8, 1966:

As of today I have 3,202 songs on my iPod, which is about all it will hold. From time to time I knock off a few old songs to make room for new ones, but for the most part I find that three thousand songs is enough, by which I mean that whenever I fire up my iPod, I never have any trouble finding something I want to hear.

My office, on the other hand, contains seven custom-built wooden CD shelves holding three thousand discs. In the past year or two, I’ve let days go by at a time without listening to any of them, and I’m sure there are at least a hundred (if not more) to which I’ve never listened, just as there is a not-inconsiderable number of books on my shelves that I’ve never read.

The sad truth is that I now spend more time reading and listening for professional reasons than I do for pleasure….

Read the whole thing here.

In 2008 I wrote an essay for National Review about Dragnet. It’s never been reprinted and isn’t available on line, and since I happen to like it a lot, I decided to post it here today. I hope you enjoy it.

* * *

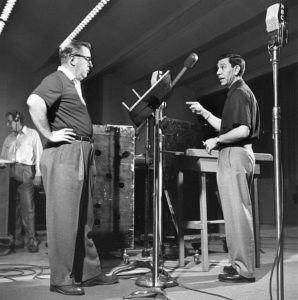

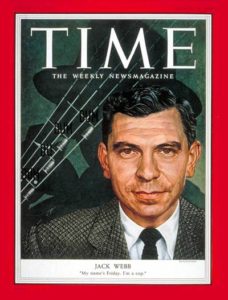

If you’re fifty or older, you won’t need to be told the source of these half-recalled phrases: “The story you are about to see is true.” “This is the city.” “I carry a badge.” “My name’s Friday.” If you’re much younger than that, though, I doubt that you’ll remember Dragnet with any clarity. In the early days of network television, Dragnet was the most successful of all cops-and-robbers TV shows, as well as the most influential. It’s still influential—every episode of Law and Order bears its indelible stamp—but TV has since moved in flashier directions, and I doubt that the narrative conventions brought into being by Jack Webb, the director, producer, and star of Dragnet, will remain conventional for much longer.

If you’re fifty or older, you won’t need to be told the source of these half-recalled phrases: “The story you are about to see is true.” “This is the city.” “I carry a badge.” “My name’s Friday.” If you’re much younger than that, though, I doubt that you’ll remember Dragnet with any clarity. In the early days of network television, Dragnet was the most successful of all cops-and-robbers TV shows, as well as the most influential. It’s still influential—every episode of Law and Order bears its indelible stamp—but TV has since moved in flashier directions, and I doubt that the narrative conventions brought into being by Jack Webb, the director, producer, and star of Dragnet, will remain conventional for much longer.

For baby-boom TV viewers, Dragnet is both iconic and ironic. The version of the show that ran on NBC from 1967 to 1970, in which Webb was partnered by Harry Morgan, was an exercise in unintended self-parody, full of hippy-dippy druggies and the earnest cops who locked them up and threw away the key. A few of the episodes remain effective in their quaint way, but most are embarrassingly stiff. Part of the problem was that Sergeant Joe Friday, Webb’s character, was the squarest of squares, and it was already chic to smirk at such straight-arrow types by the time I reached adolescence. My father watched Dragnet religiously, though, so I did, too, little knowing that what I was seeing each week was a recycled, watered-down simulacrum of the real thing.

The real Dragnet was the black-and-white version that aired from 1951 to 1959. That series, in which Webb was partnered by Ben Alexander, was pulled out of syndication long ago and has never been legitimately reissued on DVD, nor is any “official” version, so far as I know, currently in the works. Fortunately, a few dozen episodes were inadvertently allowed to go out of copyright, and it’s easy to track down copies of them. Madacy Home Video, for instance, offers a budget-priced Dragnet box set containing twenty-five decent-looking public-domain episodes, and you can acquire a dozen more from Shokus Video. At $19.98, the Madacy box is…well, a steal.

Like the later color version, the Dragnet of the Fifties was a no-nonsense half-hour police-procedural drama that sought to show how ordinary cops catch ordinary crooks. The scripts, most of which were written by James E. Moser, combined straightforwardly linear plotting (“It was Wednesday, October 6. It was sultry in Los Angeles. We were working the day watch out of homicide”) with clipped dialogue spoken in a near-monotone, all accompanied by the taut, dissonant music of Walter Schumann. Then and later, most of the shots were screen-filling talking-head closeups, a plain-Jane style of cinematography that to this day is identified with Jack Webb.

Like the later color version, the Dragnet of the Fifties was a no-nonsense half-hour police-procedural drama that sought to show how ordinary cops catch ordinary crooks. The scripts, most of which were written by James E. Moser, combined straightforwardly linear plotting (“It was Wednesday, October 6. It was sultry in Los Angeles. We were working the day watch out of homicide”) with clipped dialogue spoken in a near-monotone, all accompanied by the taut, dissonant music of Walter Schumann. Then and later, most of the shots were screen-filling talking-head closeups, a plain-Jane style of cinematography that to this day is identified with Jack Webb.

The difference was that in the Fifties, Joe Friday and Frank Smith, his chubby, mildly eccentric partner, stalked their prey in a monochromatically drab Los Angeles that seemed to consist only of shabby storefronts and bleak-looking rooms in dollar-a-night hotels. Nobody was pretty in Dragnet, and almost nobody was happy. The atmosphere was that of film noir minus the kinks—the same stark visual grammar, only cleansed of the sour tang of corruption in high places. But even without the Chandleresque pessimism that gave film noir its seedy savor, Dragnet was still rough stuff, more uncompromising than anything that had hitherto been seen on TV. In 1954 Time called the series “a sort of peephole into a grim new world. The bums, priests, con men, whining housewives, burglars, waitresses, children and bewildered ordinary citizens who people Dragnet seem as sorrowfully genuine as old pistols in a hockshop window.”

The show’s plainness was underlined by the fact that most of the scripts had originally been written by Moser for the radio version of Dragnet, which was launched in 1950. As Michael J. Hayde explains in My Name’s Friday, his excellent biography of Webb, the old scripts were filmed virtually without change when Dragnet moved to TV a year later. Webb believed that there was no need to adapt them more than superficially for the small screen—and he was right. An equally sure instinct led him to cast radio actors in the TV version of Dragnet. He didn’t care how they looked, only how they sounded, and so each episode featured such unfamiliar faces as Vic Perrin, Olan Soulé, and Virginia Gregg, whose unglamorous presence helped make the show seem, in Webb’s words, “as real as a guy pouring a cup of coffee.”

The show’s plainness was underlined by the fact that most of the scripts had originally been written by Moser for the radio version of Dragnet, which was launched in 1950. As Michael J. Hayde explains in My Name’s Friday, his excellent biography of Webb, the old scripts were filmed virtually without change when Dragnet moved to TV a year later. Webb believed that there was no need to adapt them more than superficially for the small screen—and he was right. An equally sure instinct led him to cast radio actors in the TV version of Dragnet. He didn’t care how they looked, only how they sounded, and so each episode featured such unfamiliar faces as Vic Perrin, Olan Soulé, and Virginia Gregg, whose unglamorous presence helped make the show seem, in Webb’s words, “as real as a guy pouring a cup of coffee.”

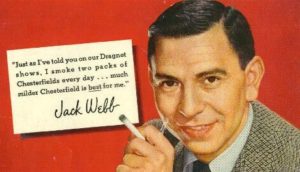

Jack Webb himself was a radio actor who lacked the good looks that would have allowed him to play star parts in Hollywood (his only role of any consequence prior to Dragnet was as William Holden’s best friend in Sunset Boulevard). It was his voice that made him unforgettable: he looked like the second cousin of an aging basset hound, but when he tossed off Moser’s crisp dialogue in a gravelly bass-baritone that reeked of the Chesterfield Kings he chain-smoked on and off screen, you hung on his every word.

Webb was a better actor than the critics knew—and a much better actor in the Fifties than he was in the Sixties. John Dunning’s On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio contains a penetrating essay on the radio version of Dragnet in which Joe Friday is aptly described as “a cop’s cop, tough but not hard, conservative but caring.” On TV Webb brought out yet another aspect of Friday, the pity he felt for the hapless losers whose paths he crossed each day. But the grueling experience of shooting 276 black-and-white episodes of Dragnet in eight years (plus a 1954 feature film based on the TV series) left its mark on Webb. By 1967 he was burned out on Dragnet, and frustrated that nobody wanted to see him do anything else. Once in a while he turned in a strong performance, but for the most part the new Dragnet was formula-ridden to the point of triteness.

Not so the original series, whose still-undiminished force is far removed from the blandness of the on-screen parody that Curtis Hanson tucked into L.A. Confidential. Hanson’s Badge of Honor mimics Dragnet’s surface mannerisms, but suggests nothing of its hard, laconic essence. While Dan Aykroyd’s affectionate 1987 film spoof was vastly more knowing, Aykroyd’s satirical target was the middle-aged Dragnet of the Sixties, in which Joe Friday and Bill Gannon chased after LSD dealers and took care to read them their rights before slapping on the cuffs. To watch its tougher predecessor is an altogether different experience, especially when Webb rattles off such furious speeches as the one he gave to a crooked policeman in a 1953 episode called “The Big Cop”:

Not so the original series, whose still-undiminished force is far removed from the blandness of the on-screen parody that Curtis Hanson tucked into L.A. Confidential. Hanson’s Badge of Honor mimics Dragnet’s surface mannerisms, but suggests nothing of its hard, laconic essence. While Dan Aykroyd’s affectionate 1987 film spoof was vastly more knowing, Aykroyd’s satirical target was the middle-aged Dragnet of the Sixties, in which Joe Friday and Bill Gannon chased after LSD dealers and took care to read them their rights before slapping on the cuffs. To watch its tougher predecessor is an altogether different experience, especially when Webb rattles off such furious speeches as the one he gave to a crooked policeman in a 1953 episode called “The Big Cop”:

You’ll be all over the front pages tonight and tomorrow morning. Everybody’s gonna read about you. A bad cop. It makes great news. They’re not gonna read about 4,500 other cops. The guys who walked their beats last night. The guys who risked their lives, who did their jobs the way they were trained and the way they’re hired to do….They’re not gonna read about the 98 percent, mister. They’re gonna read about you, one crooked, thieving cop. He worked with a burglary gang. He had an apartment for a beautiful dame and he stole her a fur coat, and he was a cop. And he had a nice wife and two fine children.

You don’t hear speeches like that on television these days, just as you won’t see anything remotely like Dragnet. Today’s TV viewers prefer blow-dried cynicism to gritty idealism. Me, I don’t watch series TV anymore, but I do like to put on an old Dragnet from time to time. I like listening to Jack Webb’s dark-brown voice—and I like to think, whether it’s true or not, that men not entirely unlike Joe Friday are still walking the streets of the anxious city where I live.

* * *

UPDATE: Prints of sixty-four black-and-white public-domain episodes of the original Dragnet are known to survive. Some of them can be viewed on YouTube, and all of them have been transferred to DVD. To order a complete set, go here.

To find out what happened to the other 203 episodes, go here.

* * *

“.22 Rifle for Christmas,” a 1952 episode of Dragnet, written by James Moser and directed by Jack Webb:

“A novelist writes a novel and people read it. But reading is a solitary act. While it may elicit a varied and personal response, the communal nature of the audience is like having five hundred people read your novel and respond to it at the same time. I find that thrilling.”

“A novelist writes a novel and people read it. But reading is a solitary act. While it may elicit a varied and personal response, the communal nature of the audience is like having five hundred people read your novel and respond to it at the same time. I find that thrilling.”

August Wilson (interviewed in the Paris Review by Bonnie Lyons and George Plimpton, Winter 1999)

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the world premiere in New Haven of Amy Herzog’s Mary Jane. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Plays whose subjects can be summed up in one word—abortion, divorce, Trump—are prone to be preachy. They needn’t be, though, and Amy Herzog’s “Mary Jane,” a play about caregiving, steers clear of every potentially fatal trap that lies in wait for an issue-driven playwright. Not only is it devoid of sermonizing, but Ms. Herzog has taken a topic that lends itself to six-hanky sentimentality and written about it in a plain-spoken, unmanipulative way. The result, exceptionally well directed by Anne Kauffman, is the best new play so far this year, one that will surely make a stir when it transfers from the Yale Repertory Theatre to the New York Theatre Workshop this fall.

The first act of “Mary Jane” takes place in the shabby little Queens apartment that the title character (Emily Donohoe), a preternaturally good-humored working woman and single mother, shares with Alex, her two-and-a-half-year-old child, who suffers from cerebral palsy. We never see Alex, who sleeps in the next room and cannot speak (he has a paralyzed vocal chord). Instead, we watch Mary Jane interact with a varied group of other women—a doctor, a nurse, the superintendent of her building, a Buddhist nun whom she meets in the hospital—who help her carry her cruel load….

The first act of “Mary Jane” takes place in the shabby little Queens apartment that the title character (Emily Donohoe), a preternaturally good-humored working woman and single mother, shares with Alex, her two-and-a-half-year-old child, who suffers from cerebral palsy. We never see Alex, who sleeps in the next room and cannot speak (he has a paralyzed vocal chord). Instead, we watch Mary Jane interact with a varied group of other women—a doctor, a nurse, the superintendent of her building, a Buddhist nun whom she meets in the hospital—who help her carry her cruel load….

Nothing much happens in “Mary Jane,” which is part conversation piece and part character study. Yet Ms. Herzog tells her tale so skillfully that it is as tense and enthralling as a mystery, while Ms. Donahoe is completely convincing in a role that in less accomplished hands could quite easily seem too good to be true, that of an ordinary woman who copes with a brutally stressful situation in a manner for which the only possible word is heroic….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The cast of Mary Jane talks about the play:

An ArtsJournal Blog