“Doubts of all things earthly, and intuitions of some things heavenly; this combination makes neither believer nor infidel, but makes a man who regards them both with equal eye.”

“Doubts of all things earthly, and intuitions of some things heavenly; this combination makes neither believer nor infidel, but makes a man who regards them both with equal eye.”

Herman Melville, Moby-Dick

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

“Drummer Man,” a 1947 film short featuring Gene Krupa, his trio, and his big band, directed by Will Cowan. The musical numbers include “Lover,” “Boogie Blues,” “Blanchette”, “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” and Eddie Finckel’s “Leave Us Leap”:

“Drummer Man,” a 1947 film short featuring Gene Krupa, his trio, and his big band, directed by Will Cowan. The musical numbers include “Lover,” “Boogie Blues,” “Blanchette”, “Stompin’ at the Savoy,” and Eddie Finckel’s “Leave Us Leap”:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“There is a view that jazz is ‘evil’ because it comes from evil people, but actually the greatest priests on 52nd Street and on the streets of New York City were the musicians. They were doing the greatest healing work. They knew how to punch through music that would cure and make people feel good.”

“There is a view that jazz is ‘evil’ because it comes from evil people, but actually the greatest priests on 52nd Street and on the streets of New York City were the musicians. They were doing the greatest healing work. They knew how to punch through music that would cure and make people feel good.”

Garth Hudson (quoted in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz)

It was back in 1995 that I met Tommy LiPuma, who produced albums by George Benson, Natalie Cole, Miles Davis, Bill Evans, João Gilberto, Dan Hicks, Paul McCartney, Randy Newman, and countless other musicians of note. I attended one of the recording sessions for Diana Krall’s All for You: A Dedication to the Nat King Cole Trio, which Tommy produced and whose liner notes I subsequently wrote. I found him charming—most people did, I gather, though I suspect he could also be scary—but there was no particular reason for the two of us to strike up an acquaintance at the time, so we didn’t.

It was back in 1995 that I met Tommy LiPuma, who produced albums by George Benson, Natalie Cole, Miles Davis, Bill Evans, João Gilberto, Dan Hicks, Paul McCartney, Randy Newman, and countless other musicians of note. I attended one of the recording sessions for Diana Krall’s All for You: A Dedication to the Nat King Cole Trio, which Tommy produced and whose liner notes I subsequently wrote. I found him charming—most people did, I gather, though I suspect he could also be scary—but there was no particular reason for the two of us to strike up an acquaintance at the time, so we didn’t.

It wasn’t until I found out eight years later that Tommy was an art collector of high seriousness that I got to know him a bit. I wrote a Washington Post column about a gallery show of his collection of paintings by American moderns, from which he learned that we shared a passion for the paintings of Arnold Friedman. A few months later he invited me over to his Manhattan apartment to look at the rest of his collection.

From then on we had lunch every couple of years, happily eating pasta and trading jazz-world and art-world gossip. He was the perfect luncheon companion, smart, likable, and utterly honest, and he had marvelous taste both as a producer and as a collector. Much to our mutual amusement, we discovered that we had once both bid on the same Friedman canvas (he won, of course—money talks). It was Tommy who suggested to me that Mrs. T and I might want to consider acquiring a lithograph by Louis Lozowick, a piece of advice that we hastened to take.

According to the obits, Tommy died on Monday “after a brief illness,” too brief for me to hear about it. Far too much time had gone by since our last meeting, which was my fault: I’ve always been shy about forcing myself on important people, and I usually let Tommy reach out and suggest lunch. Now I wish I hadn’t. I miss him already, more than I can say, and I wish I’d written more about him than that 2003 Washington Post column, the relevant part of which is reprinted below. “It’s funny how little it takes to remind you of the things you wish you hadn’t done,” I wrote many years ago. It’s not even slightly funny how little it takes to remind you of the things you put off doing until it’s too late.

* * *

I certainly can’t complain about Berry-Hill Galleries’ “High Notes of American Modernism: Selections From the Tommy and Gill LiPuma Collection,” at which I saw nine remarkable paintings by Arnold Friedman. If you’ve never heard of Friedman, who died in 1946, you’re not alone. So far as I know, none of his work is currently hanging in any museum (though the Museum of Modern Art owns a good Friedman, “Sawtooth Falls”), and he almost never gets written up nowadays. Clement Greenberg, long the top handicapper of American art, praised his late paintings to the skies, calling them “an important moment in the history of American painting.” Strong words, coming from the critic who put Jackson Pollock on the map—yet even his fervent advocacy wasn’t enough to keep Friedman’s name alive.

To understand how good Friedman was, take a long look at “Still Life (Petunias),” the prize of the LiPuma collection. In the foreground is a vase of flowers whose vibrantly colored petals all but burst off the canvas. (The thick, crusty surface was heavily worked with a palette knife.) Hanging on the wall immediately behind the vase is the lower half of an abstract painting—Friedman’s way of underlining the subtle relationship between abstraction and representation. The juxtaposition of the two genres is both witty and thought-provoking, unveiling fresh layers of implication at every glance. I was amazed to learn that “Still Life (Petunias)” was owned by Tommy and Gill LiPuma. If their names ring a bell, it’s because you probably know Tommy in a different guise: He’s a big-time record producer, the man who helped put Diana Krall on the charts. I’ve met him once or twice, but I had no idea that he and his wife were interested in art, much less that they were true connoisseurs whose independent-minded taste has inspired them to assemble what is almost certainly the largest private collection of Friedmans in the world.

To understand how good Friedman was, take a long look at “Still Life (Petunias),” the prize of the LiPuma collection. In the foreground is a vase of flowers whose vibrantly colored petals all but burst off the canvas. (The thick, crusty surface was heavily worked with a palette knife.) Hanging on the wall immediately behind the vase is the lower half of an abstract painting—Friedman’s way of underlining the subtle relationship between abstraction and representation. The juxtaposition of the two genres is both witty and thought-provoking, unveiling fresh layers of implication at every glance. I was amazed to learn that “Still Life (Petunias)” was owned by Tommy and Gill LiPuma. If their names ring a bell, it’s because you probably know Tommy in a different guise: He’s a big-time record producer, the man who helped put Diana Krall on the charts. I’ve met him once or twice, but I had no idea that he and his wife were interested in art, much less that they were true connoisseurs whose independent-minded taste has inspired them to assemble what is almost certainly the largest private collection of Friedmans in the world.

The LiPuma collection also contains 22 paintings by Alfred Maurer, a gifted American modernist who is as persistently underrated as Friedman, plus fine works by Arthur Dove, John Graham, Marsden Hartley, Walt Kuhn, John Marin and Joseph Stella. Alas, the show is no longer on view, but perhaps the Phillips Collection could be persuaded to bring it to Washington. Arnold Friedman, after all, was Duncan Phillips’s cup of tea—a color-drunk representationalist who flirted daringly with abstraction—and it would be altogether fitting if the best small museum in America were to open its doors to the least-known major American painter of the 20th century.

* * *

The Los Angeles Times obituary is here.

Diana Krall’s tribute is here.

Marc Myers’ tribute is here.

Tommy LiPuma talks about the Cleveland Museum of Art, to which he donated Marsden Hartley’s “New Mexico Recollection”:

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the Broadway transfer of Come From Away. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

On September 11, 2001, 38 commercial flights, most of them bound for the U.S., were abruptly diverted to Newfoundland’s Gander International Airport when North America’s air space was closed by Transport Canada and the FAA in the wake of terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. This forced the residents of Gander, a town of eleven thousand, to spend the next four days shouldering the collective responsibility of feeding and taking care of 6,600 unexpected guests, which they did with open-handed alacrity. Those four days are the subject of “Come From Away,” a Canadian musical written by Irene Sankoff and David Hein that has transferred to Broadway after preliminary runs in La Jolla, Ca., Seattle, and Washington, D.C. It’s a wonderful story, and I wish I could say that it’s been turned into an equally wonderful musical: You can’t help but root for such a show. But “Come From Away” is, in cold, hard point of fact, a gushily sentimental piece of theatrical yard goods that makes every mistake a musical can make.

The problems start right at the top. “Come From Away” is an unusually compact musical (100 minutes, no intermission) in which 12 actors portray a much larger number of “plane people” and locals. That’s perfectly feasible, but Ms. Sankoff and Mr. Hein have chosen to present the story of what happened in Gander on 9/11 in a tell-more-than-show manner, with the actors spending at least as much time describing events to the audience (“That morning, I drop my kids off at school…4:18 p.m. There’s a 747 with a flat tire blocking the runway”) as interacting directly with one another in dialogue scenes. The results play like a volume of oral-history transcripts set to music, and the decision of the authors not to focus tightly on specific characters results in a cluttered, top-heavy show with too much exposition and not nearly enough development. It doesn’t help that the characters, major and minor alike, are all walking clichés, as is absolutely everything that happens to them…

The problems start right at the top. “Come From Away” is an unusually compact musical (100 minutes, no intermission) in which 12 actors portray a much larger number of “plane people” and locals. That’s perfectly feasible, but Ms. Sankoff and Mr. Hein have chosen to present the story of what happened in Gander on 9/11 in a tell-more-than-show manner, with the actors spending at least as much time describing events to the audience (“That morning, I drop my kids off at school…4:18 p.m. There’s a 747 with a flat tire blocking the runway”) as interacting directly with one another in dialogue scenes. The results play like a volume of oral-history transcripts set to music, and the decision of the authors not to focus tightly on specific characters results in a cluttered, top-heavy show with too much exposition and not nearly enough development. It doesn’t help that the characters, major and minor alike, are all walking clichés, as is absolutely everything that happens to them…

These problems might have been overcome to some extent had the score to “Come From Away” been more distinctive. Instead, Ms. Sankoff and Mr. Hein have given us 15 forgettable musical numbers, most of them fragmentary, whose music is a peppy mélange of folk, pop, country and Canadian-Irish jiggery-pokery and whose lyrics defy all attempts to remember them for longer than it takes to hear them sung…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Some excerpts from Come From Away:

Last night I went to a memorial service for Jesse Simons, one of the most delightful and fascinating men I’ve had the good luck to meet. Jesse, who died last year at the age of eighty-eight, was a Trotskyist turned labor arbitrator. He became sufficiently distinguished in the latter capacity to earn both a Wikipedia entry and a New York Times obituary, neither of which mentioned that he was also a bon vivant, a ladies’ man, and an unswervingly devoted balletomane….

Read the whole thing here.

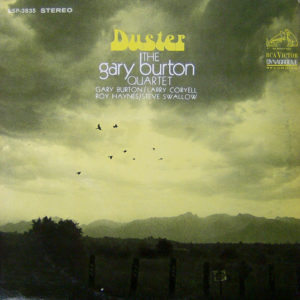

I first saw the Gary Burton Quartet on TV when I was in high school. In those days I was finding my way around the illimitably vast world of jazz, searching for a style that spoke to me personally—a jazz that felt as though it were being made for people of my time and place. The rock-inflected jazz that Burton’s group was playing in the late Sixties turned out to be exactly what I was looking for, and ever since then I’ve been a devoted fan.

Burton’s playing was already fully formed when the quartet cut its first album, Duster, in 1967. How astonishing to think that he was only twenty-four years old! He would continue to play with the same combination of staggering virtuosity and poised lyricism throughout the half-century to come, just as he continued to bring a steady stream of now-celebrated sidemen, many of them his former students, into his groups. Steve Swallow, Larry Coryell, Pat Metheny, John Scofield, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Julian Lage: all are Burton alumni, and all can testify to his unique gifts. Metheny calls him “the epitome of what a great modern musician should be…a bottomless pit of ideas and melody.”

Burton’s playing was already fully formed when the quartet cut its first album, Duster, in 1967. How astonishing to think that he was only twenty-four years old! He would continue to play with the same combination of staggering virtuosity and poised lyricism throughout the half-century to come, just as he continued to bring a steady stream of now-celebrated sidemen, many of them his former students, into his groups. Steve Swallow, Larry Coryell, Pat Metheny, John Scofield, Kurt Rosenwinkel, Julian Lage: all are Burton alumni, and all can testify to his unique gifts. Metheny calls him “the epitome of what a great modern musician should be…a bottomless pit of ideas and melody.”

I first wrote about Burton in 1981 in the Kansas City Star, back when I was a wet-behind-the-ears working jazz critic. I’ve heard him many times since then, but for some reason it never occurred to me to write about him at length—probably because he was so central a part of my musical life that I took his excellence for granted, foolishly assuming that it, and he, would always be with us. So when I read a story last month in the Miami Herald in which he unexpectedly announced that he would be retiring from public performance at the end of his current concert tour, the news hit me hard, and I resolved to do what I should have done long before.

I sent an e-mail to my editor at The Wall Street Journal and got a thumbs-up in reply, and a week later my heartfelt tribute to Burton appeared in the paper:

Playing with four mallets instead of the long-customary two, a technique that he pioneered, he fills the air with billowing pastel washes of iridescent harmony, miraculously transforming a percussion instrument into a font of cool, silvery lyricism. Watching him manipulate his mallets at something approaching Mach 2 feels a bit like chatting with a member of a more highly evolved species.

No sooner did I start writing the piece than it occurred to me to find out whether Burton was stopping in New York on his last tour. I checked his website and saw that he and the pianist Makoto Ozone, who has worked with him off and on for the past thirty-five years, were coming to Birdland. It was the worst possible weekend for me to sandwich in a nightclub visit—I’d scheduled back-to-back shows on Friday, Saturday, and Sunday—but I knew I’d hate myself if I missed Burton’s final gig in New York, so I booked a seat for the last set on Saturday, and returned to the theater district that night after fortifying myself with a post-matinée catnap.

Time was when Birdland was one of my regular haunts, so much so that I’ve been present when two live albums were recorded there. Back then, though, I was going out on the town four or five times a week in my self-defined capacity as flâneur-of-all-trades, reporting on the arts in New York each month for the Washington Post. Then I became a full-time drama critic and, not long afterward, a happily married man who divides his time between New York and rural Connecticut. Soon I found that I no longer had the time or inclination to go to clubs other than occasionally. It wasn’t that I loved jazz any less, but my newfound passion for theater was now central to my life, and I felt the growing need to devote my energies to what mattered most to me. When I showed up at Birdland at ten p.m. on Saturday, an hour when I’m usually looking for a cab to take me home from a Broadway show, it struck me that I couldn’t recall the last time I’d been there.

Fortunately, the place is still the same, as is the tasty Cajun-style cooking that has long distinguished Birdland, and no sooner did I settle into my second-row seat and order a plate of jambalaya than I felt as if I’d never been away. In due course Burton and Ozone made their entrance and went to work. I was catapulted into the moment, reveling in the artistry of a great musician whom I knew I would never again see on stage.

Fortunately, the place is still the same, as is the tasty Cajun-style cooking that has long distinguished Birdland, and no sooner did I settle into my second-row seat and order a plate of jambalaya than I felt as if I’d never been away. In due course Burton and Ozone made their entrance and went to work. I was catapulted into the moment, reveling in the artistry of a great musician whom I knew I would never again see on stage.

Burton, who has undergone six heart operations, is retiring at seventy-four because he feels that his playing has started to show the corrosive effects of age and illness. “It increasingly makes me uncomfortable when I go out on stage and I don’t feel as confident that I’m going to have a great night,” he explained in the Miami Herald. “I’m starting to have moments—what we call senior moments. I have them sometimes when I’m playing. I suddenly forget where I am in the song.” All true, no doubt, but you couldn’t have proved it by me, or anyone else at Birdland, on Saturday. He played a demanding set with an unmistakably valedictory air: Charlie Christian’s “Air Mail Special,” Chick Corea’s “Brasilia,” Swallow’s “Eiderdown,” Antônio Carlos Jobim’s “O Grande Amor,” Ozone’s “Times Like These,” Scofield’s “Why’d You Do It?” and two standard ballads, “Beautiful Love” and “For Heaven’s Sake.” All were tossed off with miraculous ease and flair, and when he tore into an arrangement for vibraphone and piano of a Scarlatti sonata, his mallets flew so fast that all you could see at the end of his hands was a mystifying blur.

I wondered how the famously matter-of-fact Burton would call it quits at evening’s end. Sure enough, he steered clear of pathos and pulled a gratifying and characteristic surprise out of his hat: Paquito d’Rivera, the jazz clarinetist, and Joseph Alessi, the principal trombonist of the New York Philharmonic, joined him and Ozone on stage for a hard-swinging jam on “Bags’ Groove,” a well-worn, well-loved blues riff by Milt Jackson, the other great modern-jazz vibraphonist of the twentieth century. Then it was all over at last, and Burton left the bandstand and was swamped by admirers.

I wondered how the famously matter-of-fact Burton would call it quits at evening’s end. Sure enough, he steered clear of pathos and pulled a gratifying and characteristic surprise out of his hat: Paquito d’Rivera, the jazz clarinetist, and Joseph Alessi, the principal trombonist of the New York Philharmonic, joined him and Ozone on stage for a hard-swinging jam on “Bags’ Groove,” a well-worn, well-loved blues riff by Milt Jackson, the other great modern-jazz vibraphonist of the twentieth century. Then it was all over at last, and Burton left the bandstand and was swamped by admirers.

It happens that I know Burton a bit, well enough that he made a point of coming to the opening of my Palm Beach Dramaworks production of Satchmo at the Waldorf last year, a gesture that filled me with pride. We’re nothing like old friends, though, and I didn’t want to force myself on him at what I felt sure would be an emotional moment, so I contented myself with sending a congratulatory e-mail when I got home. “You couldn’t possibly have left us on a higher note,” I wrote. The next morning his response was in my mailbox: “I feel really great going out on top of my game, or close to it, anyway.” So he did: I’ve never heard him play better. That is how I will always remember Gary Burton, as a silver-haired septuagenarian playing with the sacred fire and total assurance of a young man with his whole life ahead of him. We should all go out like that.

* * *

The Gary Burton Quartet plays Makoto Ozone’s “Times Like These” in 1989:

Gary Burton’s very first recording as a studio sideman, Floyd Cramer’s “Last Date,” recorded in Nashville in 1960:

An ArtsJournal Blog