“Nature has a great simplicity and, therefore, a great beauty.”

“Nature has a great simplicity and, therefore, a great beauty.”

Richard Feynman, The Character of Physical Law

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I write about Ben Hecht, co-author of The Front Page. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Ben Hecht might just be the most famous unknown writer who ever lived. He co-wrote “The Front Page,” one of the smash hits of the current Broadway season, and you’ve almost certainly seen at least a half-dozen of the hundred or so now-classic Hollywood movies on whose scripts he is known to have worked, with and without credit, between 1927 and his death in 1964. “Gone With the Wind,” “Kiss of Death,” “Nothing Sacred,” “Notorious,” “Scarface,” “Stagecoach,” “Twentieth Century,” “Wuthering Heights: All bear Hecht’s stamp in whole or part. But do you know his name? Most likely not. Nor is there much chance that you’ve read any of his two dozen books, most of them long out of print and justly forgotten.

Hecht himself wouldn’t have been surprised by his posthumous obscurity. While he poured most of his energies into the writing of screenplays, his contempt for Hollywood was acid and bottomless, and what he said of his friend Herman Mankiewicz, who co-wrote “Citizen Kane” with Orson Welles, was clearly meant to apply to himself as well: “To own a mind like Manky’s and hamstring and throttle it for 25 years in the writing only of movie scenarios is to submit your soul to a nasty strain.” Yet one of Hecht’s later books, written long after he’d sold his soul to the Celluloid God, deserves resurrection. Published in 1954, A Child of the Century, his 654-page autobiography, is by turns florid, self-regarding and sentimental to a fault. But it is also irresistibly readable, a book that can be opened at random and perused with delight….

Hecht himself wouldn’t have been surprised by his posthumous obscurity. While he poured most of his energies into the writing of screenplays, his contempt for Hollywood was acid and bottomless, and what he said of his friend Herman Mankiewicz, who co-wrote “Citizen Kane” with Orson Welles, was clearly meant to apply to himself as well: “To own a mind like Manky’s and hamstring and throttle it for 25 years in the writing only of movie scenarios is to submit your soul to a nasty strain.” Yet one of Hecht’s later books, written long after he’d sold his soul to the Celluloid God, deserves resurrection. Published in 1954, A Child of the Century, his 654-page autobiography, is by turns florid, self-regarding and sentimental to a fault. But it is also irresistibly readable, a book that can be opened at random and perused with delight….

What is most noteworthy about Hecht’s reminiscences of Hollywood is how much he hated the place: “The movies are one of the bad habits that corrupted our century….Out of the thousand writers huffing and puffing through movieland there are scarcely fifty men and women of wit or talent. The rest of the fraternity is deadwood.” It is painfully, pitifully self-evident that he believed he had sabotaged his career as a serious writer by spending so much of the second half of his life working there. Therein lies the bitter irony of his life: Except for “The Front Page,” whose machine-gun repartée would become part of the DNA of American movies, he is now remembered solely for his screenplays. Yet the product of the industry at which he sneered is now regarded far more highly by most critics than the earnest output of most of the “serious” American writers of his day, Hecht himself included….

* * *

A shorter version of this column appears in the print version of today’s Journal. To read the whole thing, go here.

The Front Page, the 1931 film version of the stage play by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur, directed by Lewis Milestone, adapted for the screen by Bartlett Cormack and Charles Lederer, and starring Adolphe Menjou and Pat O’Brien:

Donna Murphy sings Stephen Sondheim’s “Loving You,” a number from Passion, by Sondheim and James Lapine. This performance is part of a telecast of the original Broadway production, directed by Lapine, that was taped by PBS shortly after the show closed in 1995:

Donna Murphy sings Stephen Sondheim’s “Loving You,” a number from Passion, by Sondheim and James Lapine. This performance is part of a telecast of the original Broadway production, directed by Lapine, that was taped by PBS shortly after the show closed in 1995:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

Like many people, my life has been a series of goals, a things-to-do list, and at fifty I now find myself in the position, at once pleasing and disconcerting, of having accomplished most of them. As for the things I haven’t yet done, nearly all of them are things I’m no longer likely to do, assuming I ever was: I doubt, for instance, that I’ll learn a second language or write a novel or become a father. I could spend the rest of my life running in place, and I suppose that would be perfectly fine. Except that I know it wouldn’t. The time will come, if it hasn’t already, when I’ll want to try my hand at something new—and I haven’t the slightest idea what it might be….

Read the whole thing here.

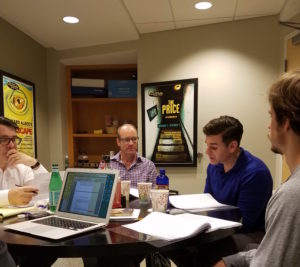

I spent most of last Thursday, Friday, and Saturday sitting in a windowless rehearsal room in downtown West Palm Beach, watching two Florida actors, Nicholas Richberg and Tom Wahl, perform bits and pieces of Billy and Me, my new play, over and over again. The three of us, guided by Bill Hayes, the artistic director of Palm Beach Dramaworks, which will present the play’s world premiere in December, went over every line in the script—and every stage direction—with the finest of fine-tooth combs. I made dozens of changes, some on the spot and others in my hotel room after each session. Most were minor, but some were highly consequential: I wrote a brand-new speech for Nick after Thursday’s session, and on Friday we collectively rewrote and polished what I’d written, rehearsed it, and inserted it into the script permanently.

I spent most of last Thursday, Friday, and Saturday sitting in a windowless rehearsal room in downtown West Palm Beach, watching two Florida actors, Nicholas Richberg and Tom Wahl, perform bits and pieces of Billy and Me, my new play, over and over again. The three of us, guided by Bill Hayes, the artistic director of Palm Beach Dramaworks, which will present the play’s world premiere in December, went over every line in the script—and every stage direction—with the finest of fine-tooth combs. I made dozens of changes, some on the spot and others in my hotel room after each session. Most were minor, but some were highly consequential: I wrote a brand-new speech for Nick after Thursday’s session, and on Friday we collectively rewrote and polished what I’d written, rehearsed it, and inserted it into the script permanently.

This process is known as “workshopping.” In recent years it’s become common practice for theater companies to workshop new plays well in advance of their premieres. The idea is to get the script in the best possible shape going in, thus allowing the actors and director to concentrate on the performances and production throughout the actual rehearsal period.

This process is known as “workshopping.” In recent years it’s become common practice for theater companies to workshop new plays well in advance of their premieres. The idea is to get the script in the best possible shape going in, thus allowing the actors and director to concentrate on the performances and production throughout the actual rehearsal period.

Most “civilians” (as lay playgoers are known to members of “the profession”) have no notion of how much work goes into a play prior to the first rehearsal. To the extent that they do know about it, their knowledge is likely to come from Moss Hart’s matchlessly vivid account in Act One, his 1959 autobiography, of how he and George S. Kaufman rewrote Once in a Lifetime mere days before it opened on Broadway in 1930. This kind of last-minute surgery still happens, of course, but a play that’s been carefully workshopped is likely to need much less of it.

That’s the theory, anyway, and in my experience it works—up to a point. Dennis Neal and I workshopped Satchmo at the Waldorf at Florida’s Rollins College seven months before its premiere in Orlando in September 2011. Moreover, the premiere, which starred Dennis and was staged by Rus Blackwell, was itself a kind of workshop, for I revised the script extensively as a result of what I learned from mounting the play down in Florida. As a result, the version of Satchmo that opened a year later in Lenox, Massachusetts, was substantially different from the one that we’d done in Orlando—and, I think, considerably better.

That’s the theory, anyway, and in my experience it works—up to a point. Dennis Neal and I workshopped Satchmo at the Waldorf at Florida’s Rollins College seven months before its premiere in Orlando in September 2011. Moreover, the premiere, which starred Dennis and was staged by Rus Blackwell, was itself a kind of workshop, for I revised the script extensively as a result of what I learned from mounting the play down in Florida. As a result, the version of Satchmo that opened a year later in Lenox, Massachusetts, was substantially different from the one that we’d done in Orlando—and, I think, considerably better.

I continued to work on Satchmo with John Douglas Thompson and Gordon Edelstein, the star and director of the Lenox production, between then and the time the show transferred to New York in March of 2014. (Among other things, I wrote an additional scene, the one in which Louis Armstrong sings a Shabbat song that he learned from the Karnofskys, the Jewish family for whom he worked as a boy in New Orleans.) Not until two weeks before our off-Broadway opening night did the script reach its final form, the official acting version of Satchmo that was published by Dramatists Play Service the following year.

That’s not how novels get written, of course, but prose fiction isn’t usually a collaborative art form, nor are novels acted out in front of live audiences. You don’t know whether a scene works until you hear and see it performed by actors, who always have invaluable suggestions that are deeply rooted in practical experience. To be sure, I did some acting in high school and college, but I wasn’t any good at it. Nick and Tom, by contrast, are very good, and whenever one of them suggests that I should reword a line—or cut it—I listen carefully to what they say. Bill Hayes, who gave me the idea for Billy and Me a year ago and who will be directing the premiere, is no less shrewd about such matters, and he and I have worked closely together on the play ever since I started writing it. Sometimes I take Bill’s suggestions, sometimes not, but I always take them very seriously.

Bill and his company have a lot riding on Billy and Me. While Palm Beach Dramaworks is a well-established regional theater company, one of the best in America, it’s never before premiered a play on its new 218-seat main stage. As for me, I had a fair amount of success with Satchmo at the Waldorf, but Billy and Me is a considerably more complex piece of work. Unlike Satchmo, a one-man-one-act play performed on a single set, Billy and Me is a two-act-two-set play in which three actors play four different characters. It’s more dramatically ambitious than Satchmo, which is, I think, as it should be. I can’t tell you how many people have told me that I should now write a one-man play about Duke Ellington! I can see why they’d think so. Still, it was important to me to try something new—and harder—this time around, and I think Billy and Me fills the bill.

Bill and his company have a lot riding on Billy and Me. While Palm Beach Dramaworks is a well-established regional theater company, one of the best in America, it’s never before premiered a play on its new 218-seat main stage. As for me, I had a fair amount of success with Satchmo at the Waldorf, but Billy and Me is a considerably more complex piece of work. Unlike Satchmo, a one-man-one-act play performed on a single set, Billy and Me is a two-act-two-set play in which three actors play four different characters. It’s more dramatically ambitious than Satchmo, which is, I think, as it should be. I can’t tell you how many people have told me that I should now write a one-man play about Duke Ellington! I can see why they’d think so. Still, it was important to me to try something new—and harder—this time around, and I think Billy and Me fills the bill.

That’s why I’m so grateful to my colleagues for spending three days helping me whip my play into shape. We put all we had into it, and we felt good about what we’d done when the five of us parted company on Saturday afternoon. Needless to say, we’ll know better when paying audiences see Billy and Me in December—but whatever the final results, I now feel confident that we’re getting somewhere.

* * *

Incidentally, today is my sixty-first birthday. Mrs. T and I aren’t doing anything out of the ordinary to mark the occasion, though. We figure it’s more than enough to be spending the week in a rented Longboat Key condo mere steps away from the Gulf of Mexico. Nor do I have any noteworthy observations to make about turning sixty-one. Truth to tell, I feel much the same way today that I did a year ago:

I have no plans, and for the moment I don’t really feel that I need any. I suppose I could spend the rest of my life running in place, but I’m pretty sure I won’t. And if such should prove to be my fate, then at least I’ll be running in tandem—which is, after all, what matters most.

Of course I’m not running in place, any more than I was last February. I was preparing to make my debut as a stage director a year ago, and this year I’m working on my second play. And while I’ve no idea what I’ll be doing next year, I’m not losing any sleep worrying about it. That’s not to say I don’t have any worries, merely that I’m prepared—at least for now—to take things as they come. Today I’m going to write a Wall Street Journal column about Ben Hecht. Tonight Mrs. T and I plan to watch the sun set and get ourselves a good dinner. Tomorrow will have to take care of itself. It always does, one way or another.

Of course I’m not running in place, any more than I was last February. I was preparing to make my debut as a stage director a year ago, and this year I’m working on my second play. And while I’ve no idea what I’ll be doing next year, I’m not losing any sleep worrying about it. That’s not to say I don’t have any worries, merely that I’m prepared—at least for now—to take things as they come. Today I’m going to write a Wall Street Journal column about Ben Hecht. Tonight Mrs. T and I plan to watch the sun set and get ourselves a good dinner. Tomorrow will have to take care of itself. It always does, one way or another.

The opening scene of John Doyle’s 2006 Broadway revival of Company, starring Raúl Esparza as Bobby. The songs are by Stephen Sondheim and the book is by George Furth. This performance was taped for broadcast on PBS’ Great Performance:

The opening scene of John Doyle’s 2006 Broadway revival of Company, starring Raúl Esparza as Bobby. The songs are by Stephen Sondheim and the book is by George Furth. This performance was taped for broadcast on PBS’ Great Performance:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

An ArtsJournal Blog