“I have never wished there was a God to call on—I have often wished there was a God to thank.”

“I have never wished there was a God to call on—I have often wished there was a God to thank.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, notebook entry, The Crack-Up

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review a Florida production of a new stage version of The Great Gatsby. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

“The Great Gatsby” is a novel short enough to aspire to perfection and good enough to approach it. Every character is memorable, every sentence unostentatiously lapidary. In addition, it says something essential about America’s national character, which F. Scott Fitzgerald embodied in the elusive person of Jay Gatsby, the original “Mr. Nobody from Nowhere.” A self-defined, self-deluding man, he made himself over into what he longed to be—and paid the price for it. No surprise, then, that so many attempts have been made to translate “Gatsby” into other media, including John Harbison’s 1999 operatic adaptation and a half-dozen different screen versions. All of them, however, have been futile, partly because of the nature of the novel, which is an intimate, almost undramatic conversation piece, and partly because Fitzgerald’s quicksilver tale needs nothing more than words on the page to make its indelible effect.

Nevertheless, Simon Levy has given it yet another try with his stage version of “Gatsby,” which received its premiere in 2006 at Minneapolis’ Guthrie Theater and has now made its way south to Florida’s Orlando Shakespeare Theater, a regional company that goes in for staged versions of classic novels (“Nicholas Nickleby,” “Pride and Prejudice” and “To Kill a Mockingbird” have all been mounted there with memorable skill in recent seasons). Mr. Levy’s “Gatsby” is short—two acts, two hours—and straightforward to a fault and beyond, a plot-intensive, dialogue-driven adaptation. Virtually all of Nick Carraway’s first-person narration, the wellspring of the novel’s color and character, has been ruthlessly excised. Imagine listening to a familiar opera performed with piano accompaniment and you’ll get the idea: The “tunes” are still there, but there’s not much left in the way of atmosphere.

Nevertheless, Simon Levy has given it yet another try with his stage version of “Gatsby,” which received its premiere in 2006 at Minneapolis’ Guthrie Theater and has now made its way south to Florida’s Orlando Shakespeare Theater, a regional company that goes in for staged versions of classic novels (“Nicholas Nickleby,” “Pride and Prejudice” and “To Kill a Mockingbird” have all been mounted there with memorable skill in recent seasons). Mr. Levy’s “Gatsby” is short—two acts, two hours—and straightforward to a fault and beyond, a plot-intensive, dialogue-driven adaptation. Virtually all of Nick Carraway’s first-person narration, the wellspring of the novel’s color and character, has been ruthlessly excised. Imagine listening to a familiar opera performed with piano accompaniment and you’ll get the idea: The “tunes” are still there, but there’s not much left in the way of atmosphere.

Up to a point, good acting can offset such grievous losses, and Matthew Goodrich’s Errol Flynn-like performance in the title role is very fine. His cool, offhand poise is like an elegantly cut but threadbare suit through which you can see Gatsby’s longing and desperation….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

Here’s my list of recommended Broadway, off-Broadway, and out-of-town shows, updated weekly. In all cases, I gave these shows favorable reviews (if sometimes qualifiedly so) in The Wall Street Journal when they opened. For more information, click on the title.

BROADWAY:

• Dear Evan Hansen (musical, PG-13, all shows sold out last week, reviewed here)

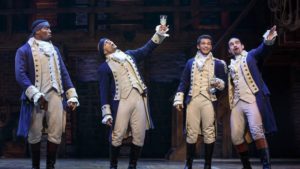

• Hamilton (musical, PG-13, Broadway transfer of off-Broadway production, all shows sold out last week, reviewed here)

• Hamilton (musical, PG-13, Broadway transfer of off-Broadway production, all shows sold out last week, reviewed here)

• On Your Feet! (jukebox musical, G, reviewed here)

OFF BROADWAY:

• The Fantasticks (musical, G, suitable for children capable of enjoying a love story, reviewed here)

IN SARASOTA, FLA.:

• Born Yesterday (comedy, PG-13, closes April 15, reviewed here)

In today’s Wall Street Journal “Sightings” column I write about the California Symphony’s new millennial outreach initiative. Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

Everybody in the fine arts is asking the same question: How do you persuade millennials, accustomed as they are to the split-second convenience of hand-held on-demand entertainment, to get off their couches and see your shows? Some of the shrewdest answers are coming from the California Symphony, which has redesigned its website in response to the input of under-35 concertgoers.

The California Symphony is a regional ensemble based in Walnut Creek, a suburb of San Francisco. Its official mission is “to become a 21st-century orchestra, making classical music relevant to those we serve, bringing in new audiences along the way.” To that end, the management has launched “Orchestra X,” a new program aimed at “a group of millennials and Gen-Xers that could or should go to orchestra concerts…but for whatever reason just doesn’t attend.” Locals who fit the profile were invited to attend the first concert of the season, paying just $5 to get in. Those who accepted the invitation visited the orchestra’s website, then wrote down their responses to the site and the concert. Afterward, they came to a pizza-and-beer party at which they “report[ed] back on their experience—the good, the bad, and the ugly.” The results were subsequently published on Medium, a youth-oriented app that runs stories written by its readers….

The California Symphony is a regional ensemble based in Walnut Creek, a suburb of San Francisco. Its official mission is “to become a 21st-century orchestra, making classical music relevant to those we serve, bringing in new audiences along the way.” To that end, the management has launched “Orchestra X,” a new program aimed at “a group of millennials and Gen-Xers that could or should go to orchestra concerts…but for whatever reason just doesn’t attend.” Locals who fit the profile were invited to attend the first concert of the season, paying just $5 to get in. Those who accepted the invitation visited the orchestra’s website, then wrote down their responses to the site and the concert. Afterward, they came to a pizza-and-beer party at which they “report[ed] back on their experience—the good, the bad, and the ugly.” The results were subsequently published on Medium, a youth-oriented app that runs stories written by its readers….

What the California Symphony discovered, in short, was that “almost every single piece of negative feedback was about something other than the performance.” Another key discovery was that it’s single-ticket buyers, not veteran subscribers, who are most likely to use the orchestra’s website. They’re less experienced in the sometimes arcane ways of classical concertgoing—but far from stupid: “We can be informative to smart, curious people who want to learn and want to know very much why each concert is special without dumbing it down. Casual and approachable does not equal dumb.”

Go to californiasymphony.org and you’ll see how the orchestra is responding to millennial input….

What is most striking about these changes is that you don’t have to be under 35 to appreciate them. Now that public-school arts education is on the way to becoming a thing of the distant past, they’re common-sense responses to the unmet needs of potential concertgoers of all ages…

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

A video featurette about the California Symphony’s Young American Composer-In-Residence program:

James Cagney appears as the mystery guest on What’s My Line? This episode was originally telecast by CBS on May 15, 1960. The panelists are Bennett Cerf, Arlene Francis, Dorothy Kilgallen, and Gore Vidal and the host is John Charles Daly:

James Cagney appears as the mystery guest on What’s My Line? This episode was originally telecast by CBS on May 15, 1960. The panelists are Bennett Cerf, Arlene Francis, Dorothy Kilgallen, and Gore Vidal and the host is John Charles Daly:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

As regular readers of this blog know, I have long searched in vain for the source of a pithy remark allegedly made by Gustave Flaubert that Irving Babbitt quoted in connection with H.L. Mencken in Rousseau and Romanticism, one of my favorite books. I liked it so much that I cited it in The Skeptic, my Mencken biography:

As regular readers of this blog know, I have long searched in vain for the source of a pithy remark allegedly made by Gustave Flaubert that Irving Babbitt quoted in connection with H.L. Mencken in Rousseau and Romanticism, one of my favorite books. I liked it so much that I cited it in The Skeptic, my Mencken biography:

More important, though, Babbitt was the first of Mencken’s critics to suggest that his noisy war against the booboisie had at last reached the point of diminishing returns: “One is reminded in particular of Flaubert, who showed a diligence in collecting bourgeois imbecilities comparable to that displayed by Mr. Mencken in his Americana. Another discovery of Flaubert’s may seem to him more worthy of consideration. ‘By dint of railing at idiots,’ Flaubert reports, ‘one runs the risk of becoming idiotic oneself.’”

Would that Babbitt had given a source for this perfectly balanced sentence! I’ve publicly asked on more than one occasion whether any of my readers could trace it to its source, until now to no avail. Then, a couple of weeks ago, I heard from Paul Chipchase, a Francophone scholar who wrote as follows:

I think the quotation from Flaubert about running the risk of becoming idiotic oneself is hard to trace because it has been slightly modified to make it more widely applicable and more amusing. I don’t know by whom.

It looks to me as if the original source of the quotation is this: “A force de nous inquiéter des imbéciles, il y a danger de le devenir soi-même” (By dint of worrying about idiots, there is a danger that we will become stupid ourselves).

Flaubert is speaking of his father’s fear of working as a doctor in a mental hospital because dealing constantly with mad people will make you vulnerable to madness yourself. This memory of his father comes up because Flaubert has just been mocking savagely a piece of recent travel writing by Louis Enault, who has been to Italy and described his journey. He starts criticising other things Enault has written and then pulls himself up short by saying that dwelling too much on second-rate stuff, even to make fun of it, will turn you into an idiot yourself: “Vois-tu le voyage qu’Énault publiera à son retour d’Italie! C’est un polisson et un drôle que de faire un article aussi cavalier que celui-là sur quelqu’un chez qui l’on a dîné sans le lui avoir rendu. Quant à l’article, il est tout simplement bête….Non, si l’on s’arrête à tout cela, et je le dis sérieusement, il y a danger de devenir idiot. Mon père répétait toujours qu’il n’aurait jamais voulu être médecin d’un hôpital de fous, parce que si l’on travaille sérieusement la folie, on finit parfaitement bien par la gagner.—Il en est de même de tout cela. A force de nous inquiéter des imbéciles, il y a danger de le devenir soi-même.”

This is on p. 645 of the new augmented edition of Flaubert’s correspondence, 2014, accessible on the Internet, where I found it, but the older ones have it, too: 1910 edition, Conard, vol. 3, p. 299. It is in Flaubert’s letter to Louise Colet, 28th-29th June 1853. This doesn’t seem to be included in Francis Steegmuller’s English translation of the letters to Louise Colet. There is a not very sprightly English version of it among the extracts from letters at the back of the Bouvard and Pécuchet volume of the 1904 complete works of Flaubert: “You must see the story of the journey that Enault has published on his return from Italy! He is a wag and a droll fellow, who will make an article in that cavalier fashion upon one with whom he has dined without first asking his permission. As for the article, it is simply stupid…No, if one does not keep himself from all this, I say it in all seriousness, there is danger of his becoming an idiot. My father said repeatedly that he never would wish to be a doctor in a hospital for the insane, because if one dealt seriously with madness, he ended by becoming mad himself. It is the same in this case; from becoming too much disturbed by these imbeciles, there is danger of becoming such ourselves.”

The crucial words at the end lack the idea of mocking or railing at imbeciles, even though that’s what Flaubert was doing in the earlier part of the paragraph. Maybe someone else will be able to come up with a closer match to your original version.

That I very much doubt! I rejoice in the solution of this problem, which has nagged at me off and on for a quarter of a century. To you, Paul Chipchase, I doff my hat in gratitude.

An ArtsJournal Blog