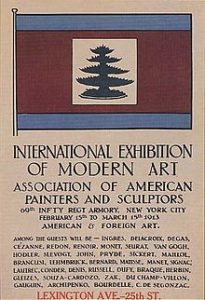

A historian I know reminded me the other day that Theodore Roosevelt attended and wrote about the 1913 Armory Show, the first major exhibition of modern art to be held in America. What’s more, he liked a fair amount of what he saw there, singling out Cézanne, Monet, Odilon Redon, and Arthur B. Davies for favorable mention.

A historian I know reminded me the other day that Theodore Roosevelt attended and wrote about the 1913 Armory Show, the first major exhibition of modern art to be held in America. What’s more, he liked a fair amount of what he saw there, singling out Cézanne, Monet, Odilon Redon, and Arthur B. Davies for favorable mention.

Alas, Roosevelt had no use whatsoever for the cubists and other “European extremists” whose work was also on display at the Armory Show, and he had particularly sharp words about Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, which he regarded as exemplary of the “lunatic fringe” of modern art. His remarks on the painting can be found in one of his books, a 1913 collection of essays called History as Literature, and they’re worth reading and pondering:

Take the picture which for some reason is called “A Naked Man Going Down Stairs.” There is in my bathroom a really good Navajo rug which, on any proper interpretation of the Cubist theory, is a far more satisfactory and decorative picture. Now, if, for some inscrutable reason, it suited somebody to call this rug a picture of, say, “A Well-Dressed Man Going Up a Ladder,” the name would fit the facts just about as well as in the case of the Cubist picture of the “Naked Man Going Down Stairs.” From the standpoint of terminology each name would have whatever merit inheres in a rather cheap straining after effect; and from the standpoint of decorative value, of sincerity, and of artistic merit, the Navajo rug is infinitely ahead of the picture.

It’s easy—too easy—to sneer at the alleged philistinism of Roosevelt’s response to “Nude Descending a Staircase.” What I find vastly more interesting, by contrast, is that he had an opinion about the painting, and expressed it so clearly and compellingly. Can you think of another president who’s had anything whatsoever to say about modern art?

It’s easy—too easy—to sneer at the alleged philistinism of Roosevelt’s response to “Nude Descending a Staircase.” What I find vastly more interesting, by contrast, is that he had an opinion about the painting, and expressed it so clearly and compellingly. Can you think of another president who’s had anything whatsoever to say about modern art?

I last had occasion to write about Theodore Roosevelt’s aesthetic interests thirteen years ago in this space, apropos of the publication of a Library of America volume of his letters and speeches that was edited by no less a literary light than Louis Auchincloss. It contained an 1884 letter in which Roosevelt had some exceedingly interesting things to say about Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina:

That Roosevelt was a good writer is no secret. But what interests me even more about this particular passage is that it’s a rare example of a prominent American politician saying something specific on paper about an important work of art….No doubt Lincoln makes mention of Shakespeare in his letters, and I think it fairly likely that Harry Truman, who was a pianist with a serious interest in classical music, must have written somewhere or other about Chopin. But who else? Outside of Justice Holmes, a literary connoisseur but not a politician in the strict sense of the word, no names come immediately to mind.

This lack of aesthetic interest isn’t unique to politicians, of course. I know of very few American men of affairs (to exhume a wonderfully musty old phrase) who have much of anything to do with art other than as collectors, in which capacity they not infrequently develop considerable sophistication over time. But ask them to talk about the art they own and they have a way of coming up short. This doesn’t necessarily mean they get no aesthetic pleasure out of their art–intellectuals have a nasty habit of regarding verbal dexterity as a virtue, invariably to their cost–but it does make you wonder.

All this, of course, comes to mind in light of the fact that President Trump is reported to be seriously considering the possibility of defunding the National Endowment for the Arts. True or not, it’s hardly a secret that Trump has no interest in the fine arts, and that his taste in décor is—shall we say—just the least little bit over the top.

This has been the cause of much sniggering by the cognoscenti, not least because President Obama gave an interview last month in which he spoke in some detail about his taste in literature, making special mention of a novel about which you wouldn’t have expected him to express admiration:

V.S. Naipaul’s novel A Bend in the River, Mr. Obama recalls, “starts with the line ‘The world is what it is; men who are nothing, who allow themselves to become nothing, have no place in it.’ And I always think about that line and I think about his novels when I’m thinking about the hardness of the world sometimes, particularly in foreign policy, and I resist and fight against sometimes that very cynical, more realistic view of the world. And yet, there are times where it feels as if that may be true.”

Needless to say, I take it for granted that politicans who talk about art for public consumption have been carefully briefed in advance. It’s no secret that President Kennedy’s alleged interest in the fine arts was in fact a concoction of his aides (his taste ran more to the novels of Ian Fleming). But Obama certainly gave a convincing impression in this interview of being a man who takes fiction seriously, and we have it on good authority that George W. Bush, in addition to being a passionate amateur painter, is also a voracious reader whose nightstand has held, among other interesting things, Albert Camus’ The Stranger.

Needless to say, I take it for granted that politicans who talk about art for public consumption have been carefully briefed in advance. It’s no secret that President Kennedy’s alleged interest in the fine arts was in fact a concoction of his aides (his taste ran more to the novels of Ian Fleming). But Obama certainly gave a convincing impression in this interview of being a man who takes fiction seriously, and we have it on good authority that George W. Bush, in addition to being a passionate amateur painter, is also a voracious reader whose nightstand has held, among other interesting things, Albert Camus’ The Stranger.

My question is this: ought we to care whether politicians take any kind of interest in the fine arts? It is, after all, a well-known fact that no twentieth-century political leader was more deeply interested in art than Adolf Hitler. As I wrote in a 2003 essay for Commentary called “The Murder Artist,” Hitler’s involvement in the arts “was—as far as it went—perfectly serious. Though his own abilities as a painter and architect were limited, they were real, just as his love of music was within its own narrow limits both intense and well-informed.” If that passion made him less monstrous, I’m not aware of it.

Don’t get me wrong: I’d like it if more politicians appreciated the role of the fine arts in American life. Nevertheless, I think it’s silly to expect them to appreciate art, much less to suppose that doing so would make them better people. Clement Greenberg said it: “Art solves nothing, either for the artist himself or for those who receive his art.” This doesn’t mean that the love of art is anything other than enriching to those who appreciate it. But only a fool believes that the experience of art necessarily makes you a better person: it is a more or less intense form of pleasure, and for most people that’s as far as it goes. Having dedicated myself to the arts, I don’t like to think that this should be the case, and sometimes it isn’t. To behold and meditate on beauty can be ennobling—but not always.

Which brings us back to Theodore Roosevelt, who happens to be the only American president to date who has himself inspired an indisputably first-class work of visual art, the official White House portrait that John Singer Sargent painted in 1903. Roosevelt, as well he should have, liked it very much, though I wouldn’t have been surprised had he taken against it, given the circumstances in which it was painted. According to Edmund Morris, “[t]he noticeable sadness in [Roosevelt’s] eyes may reflect the fact that his wife, even as he posed, was suffering her second miscarriage in two years.”

Which brings us back to Theodore Roosevelt, who happens to be the only American president to date who has himself inspired an indisputably first-class work of visual art, the official White House portrait that John Singer Sargent painted in 1903. Roosevelt, as well he should have, liked it very much, though I wouldn’t have been surprised had he taken against it, given the circumstances in which it was painted. According to Edmund Morris, “[t]he noticeable sadness in [Roosevelt’s] eyes may reflect the fact that his wife, even as he posed, was suffering her second miscarriage in two years.”

Nevertheless, he was pleased by the painting, as was I when I saw it hanging in the East Room of the White House a decade ago. It pleases me, too, that a president who was so responsive to art should have been painted so impressively well, just as it pleases me to know that Teddy Roosevelt liked Cézanne’s Old Woman With Rosary and thought Tolstoy “a great writer.” And did any of this make him a better president, or a better man? I regretfully take leave to doubt it.

* * *

The voice of Theodore Roosevelt, recorded in 1912:

A 1968 BBC interview with Marcel Duchamp: