Mrs. T and I arrived on Sanibel Island nine days ago, a week later than we’d originally planned. Despire the unraveling of our expectations, the same thing happened to me that’s been happening ever since we first started going to Florida each January: I started to unwind as soon as we drove across the long bridge that links Sanibel to the mainland, and within a matter of hours I felt almost like a different person. Almost, you understand: I haven’t arrived quite yet, but I’m well on the way.

Mrs. T and I arrived on Sanibel Island nine days ago, a week later than we’d originally planned. Despire the unraveling of our expectations, the same thing happened to me that’s been happening ever since we first started going to Florida each January: I started to unwind as soon as we drove across the long bridge that links Sanibel to the mainland, and within a matter of hours I felt almost like a different person. Almost, you understand: I haven’t arrived quite yet, but I’m well on the way.

Since then I’ve seen a play in Fort Myers and written a couple of Wall Street Journal pieces. Exclusive of that, I’ve done no work at all, at least not of the deadline-driven sort. Instead, I’ve been tinkering with the script of my second play, whose premiere will be announced in this space and elsewhere at some point in the next couple of weeks. In addition, I’ve read a short stack of books purely for pleasure—four Patrick O’Brian novels and biographies of Leadbelly and Fredric March—and Mrs. T and I went to Sanibel’s lone movie house over the weekend to see Kenneth Lonergan’s Manchester by the Sea, a rare treat for us (we saw a grand total of three films in a theater in 2016).

I can’t remember the last time I was so deeply moved by a film—or a play, for that matter—as I was by Manchester by the Sea. I’m in awe of Lonergan’s ability to move without apparent effort from the stage to film and back again. I wonder whether there has ever been a writer-director who worked with equal force and assurance in the two media. Nor can I think of another work of art that is truer to the real-life experiences of death and mourning. I can’t imagine what it would feel like for a parent to see such a film. It put me forcibly in mind of Gloucester’s terrible line in King Lear: As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods. As for me, I rank Manchester by the Sea right alongside Horton Foote’s Tender Mercies. It’s one of those rare works of dramatic art that makes me want to work harder than ever to be a better artist.

I can’t remember the last time I was so deeply moved by a film—or a play, for that matter—as I was by Manchester by the Sea. I’m in awe of Lonergan’s ability to move without apparent effort from the stage to film and back again. I wonder whether there has ever been a writer-director who worked with equal force and assurance in the two media. Nor can I think of another work of art that is truer to the real-life experiences of death and mourning. I can’t imagine what it would feel like for a parent to see such a film. It put me forcibly in mind of Gloucester’s terrible line in King Lear: As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods. As for me, I rank Manchester by the Sea right alongside Horton Foote’s Tender Mercies. It’s one of those rare works of dramatic art that makes me want to work harder than ever to be a better artist.

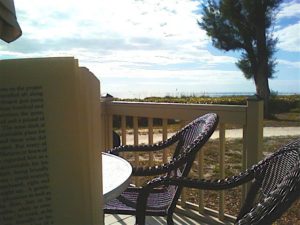

What else have I done? Well, I’ve sat on the back porch every afternoon and gazed at the water. I’ve taken Mrs. T to dinner, or brought it back to our beach bungalow, every evening. And on Thursday we took a sunset cruise around Captiva, Sanibel’s neighboring island, and watched a school of dolphins frolic in the Gulf of Mexico. Mrs. T loves dolphins, and I love to watch her watching them, almost as much as I love being on the water. I grew up in a small, land-locked town in southeast Missouri, and my belated discovery of the sight and sound—and smell—of oceans has been one of the supreme pleasures of my middle age.

Our cruise came equipped with a memento mori of sorts: the sound system of the boat on which we cruised around Captiva Island played moldy oldies. One of them was the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young cover version of Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock,” which was recorded in 1970, the year I turned fourteen, an age at which it is still possible not to wince at lines like “We are stardust/We are golden/We are billion-year-old carbon.” As it played not-so-softly in the background, I leaned over to Mrs. T and whispered, “This is our generation’s nostalgia music, God help us.” And so it is: “Woodstock” is to the baby boomers what “Moonlight Serenade” was to my late parents. Somehow I don’t think we made on the deal.

Our cruise came equipped with a memento mori of sorts: the sound system of the boat on which we cruised around Captiva Island played moldy oldies. One of them was the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young cover version of Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock,” which was recorded in 1970, the year I turned fourteen, an age at which it is still possible not to wince at lines like “We are stardust/We are golden/We are billion-year-old carbon.” As it played not-so-softly in the background, I leaned over to Mrs. T and whispered, “This is our generation’s nostalgia music, God help us.” And so it is: “Woodstock” is to the baby boomers what “Moonlight Serenade” was to my late parents. Somehow I don’t think we made on the deal.

Even so, I have no other complaints about the week just past, save that it wasn’t twice as long. I doubt I would have been able to say as much fifteen years ago. As I’ve mentioned more than once in this space, it was hard for me to learn in adulthood the precious, indispensable art of leisure. I’m pretty sure I know why:

I’ve decided to blame this idiosyncrasy on my late father, who planned the family vacations of my youth on the mistaken assumption that the point of going somewhere is to do something. An anxious, restless man, he was never much good at doing nothing, whereas it seemed self-evident to me from childhood onward that the whole point of taking a vacation was to do whatever you wanted—including nothing—whenever you wanted.

Between my father’s unfortunate example and the fact that I have the good fortune to do something for a living that I love, I’ve become something of a workaholic—but not a degenerate one. It took long enough, but experience has finally taught me the value of doing nothing in particular. Not only does leisure recharge my creative batteries, but it is, as Josef Pieper reminds us, good in and of itself: “Unless we regain the art of silence and insight, the ability for non-activity, unless we substitute true leisure for our hectic amusements, we will destroy our culture—and ourselves.”

I wish I’d learned that lesson sooner, but I’m so glad I know it now that I feel no need to repine. To sit in a rocking chair on the back porch of a beach bungalow, alternately reading and looking out at the Gulf of Mexico: that is heaven. It reminds me of something Dr. Johnson said to Boswell: “If I had no duties, and no reference to futurity, I would spend my life in driving briskly in a post-chaise with a pretty woman.” I’d most likely spend mine on Sanibel Island with Mrs. T, who is both pretty and excellent company.

I wish I’d learned that lesson sooner, but I’m so glad I know it now that I feel no need to repine. To sit in a rocking chair on the back porch of a beach bungalow, alternately reading and looking out at the Gulf of Mexico: that is heaven. It reminds me of something Dr. Johnson said to Boswell: “If I had no duties, and no reference to futurity, I would spend my life in driving briskly in a post-chaise with a pretty woman.” I’d most likely spend mine on Sanibel Island with Mrs. T, who is both pretty and excellent company.

Anyway, that’s what I’ve been up to since you last heard from me: nothing in particular. I’ll be driving up to Sarasota on Sunday afternoon to review another show, but otherwise my plan is to continue as before, at least until I’m recaptured by the tentacles of dailyness—and even then I won’t give up without a fight. Sufficient unto the day is the leisure thereof.

* * *

To read a New Yorker profile by Rebecca Mead in which Kenneth Lonergan talks about the making of Manchester by the Sea, go here.

The trailer for Manchester by the Sea:

A scene from Blake Edwards’ 10, in which Dudley Moore and Brian Dennehy talk about the music of their youth: