“Sweeping, confident articles on the future seem to me, intellectually, the most disreputable of all forms of public utterance.”

“Sweeping, confident articles on the future seem to me, intellectually, the most disreputable of all forms of public utterance.”

Kenneth Clark, script for Civilisation

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

For all its increasingly aggressive incivility, I still get a fair amount of pleasure out of Twitter, enough so that I continue to take part in threads which amuse me sufficiently. Here’s a recent one: “Without revealing your actual age, what is something you remember that if you told a younger person, they wouldn’t understand?” This is a topic to which I’ve given much thought in the past, so it didn’t take much time for me to respond with “My grandmother had a party line.” I often wonder what viewers under the age of sixty make of the premise of Pillow Talk, the 1959 movie in which Rock Hudson and Doris Day play two strangers who share a Manhattan party line, though I dare say there are quite a few other things about Pillow Talk that confuse them even more.

For all its increasingly aggressive incivility, I still get a fair amount of pleasure out of Twitter, enough so that I continue to take part in threads which amuse me sufficiently. Here’s a recent one: “Without revealing your actual age, what is something you remember that if you told a younger person, they wouldn’t understand?” This is a topic to which I’ve given much thought in the past, so it didn’t take much time for me to respond with “My grandmother had a party line.” I often wonder what viewers under the age of sixty make of the premise of Pillow Talk, the 1959 movie in which Rock Hudson and Doris Day play two strangers who share a Manhattan party line, though I dare say there are quite a few other things about Pillow Talk that confuse them even more.

The deaths of Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds led to an even more interesting thread: “What was the first celebrity death to really punch you in the gut?” I can just remember the day when President Kennedy was shot, but I was too young for his death to make an emotional impression on me. The murders of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy took place five years later, by which time I had some appreciation of what it meant for two such men to have been shot down at a two-month interval. Even so, I was just twelve years old, still too young to grasp how consequential their deaths were. In any case, it’s not right to speak of the assassinations of King and the Kennedys as “celebrity deaths”: they were historical figures, not “celebrities,” and their deaths, like their lives, changed the world.

The first true “celebrity death” that made a significant impression on me was that of Michael Conrad, one of the stars of Hill Street Blues, a TV series that I watched faithfully every Thursday. Conrad died of cancer in 1983, four years into the run of the show, and his death was incorporated into a later episode. By then his character, Phil Esterhaus, seemed almost as familiar to me as a friend, in part because he and the other characters on the show were portrayed so vividly and intimately.

The first true “celebrity death” that made a significant impression on me was that of Michael Conrad, one of the stars of Hill Street Blues, a TV series that I watched faithfully every Thursday. Conrad died of cancer in 1983, four years into the run of the show, and his death was incorporated into a later episode. By then his character, Phil Esterhaus, seemed almost as familiar to me as a friend, in part because he and the other characters on the show were portrayed so vividly and intimately.

Since then, though, I can’t say that the death of any celebrity has “punched me in the gut.” Perhaps this is a function of the fact that I’ve now lived long enough to lose numerous real-life family members and intimate friends, something that was not yet the case in 1983. Whatever the reason, I was unresponsive to the outpouring of social-media sentiment that was triggered by the passing of (among others) Fisher, Reynolds, Edward Albee, Muhammad Ali, David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, George Michael, Prince, Alan Rickman, Garry Shandling, and Gene Wilder. Why should this be so? The reason, I think, is that while I admired some of these men and women, one or two greatly, I didn’t know any of them, nor did their lives and work shape my character or taste, as a good many of my (mostly) younger women friends claim to have been shaped by Carrie Fisher’s example.

This kind of detachment can offend those who partake fully of such feelings. I found that out when, eleven years ago, I wrote in this space about the death of Johnny Carson, in the process enraging many people who thought it inappropriate for me to coolly suggest that Carson’s fame would prove—as has indeed been the case—to be ephemeral.

None of this means that I’m incapable of grasping what it means to be moved by the death of a celebrity. On the night that Debbie Reynolds died, I watched Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo for the first time. I dislike most of Allen’s work, but I was touched to the heart by this particular film, in which Mia Farrow plays the part of an unhappily married waitress who goes to the movies in search of the emotional fulfillment that real life has failed to give her. I know how she felt. I see myself as a mostly happy person, yet one of the reasons why I immerse myself in the world of art is that it has the power to console me for the fearful trials of life. More than a few things have happened to me in my sixty years that I would have found hard to survive without such consolation, and I am profoundly grateful to the artists whose work has given it to me.

Nevertheless, there is for me an unbridgeable gap between admiration from a distance, however strong, and the more personal sentiment that for me is inextricably tied up with personal acquaintance. I had occasion last year to write The Wall Street Journal’s obituary for Brian Friel, a very great artist whom I never met in person but whose work spoke to me in a deeply personal way. Yet I can’t honestly say that I felt his death, at least not in the same way that I felt the death of, say, Jim Hall, another great artist whom I did know:

Nevertheless, there is for me an unbridgeable gap between admiration from a distance, however strong, and the more personal sentiment that for me is inextricably tied up with personal acquaintance. I had occasion last year to write The Wall Street Journal’s obituary for Brian Friel, a very great artist whom I never met in person but whose work spoke to me in a deeply personal way. Yet I can’t honestly say that I felt his death, at least not in the same way that I felt the death of, say, Jim Hall, another great artist whom I did know:

I knew him a bit, well enough to say hello after a gig, and I knew dozens of musicians who worked with him and esteemed him without limit. None of them ever had a bad word to say about him, at least not in my hearing. It goes without saying that not all great artists are good people, but Mr. Hall was by all accounts a genuinely kind and decent person, altogether admirable as a husband, father and colleague.

I don’t think a cold fish could have written that paragraph. Nor do I think that I was being insincere when I ended my online tribute to Brian Friel with this sentence: “The stage of the world feels empty this morning.” He meant something to me, something very big. But did I shed any tears for him? Not a one—even though I’ve wept more than once while watching his plays.

At any rate, that’s why I didn’t have anything to say about Carrie Fisher’s death, here or elsewhere. I thought she was a good actor and a good writer, and if you cried when she died, I wouldn’t dream of sneering at you for it. But one can only feel what one feels, and I felt nothing. That is, quite literally, just me.

* * *

The theatrical trailer for Pillow Talk, directed by Michael Gordon and starring Rock Hudson and Doris Day:

The last scene of Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo, starring Mia Farrow:

I sometimes find myself temporarily disarmed by a movie that is smart on the surface; less often, a film may simulate smartness so effectively that I go home thinking it was good, and only later realize that I’ve been hornswoggled. Joel and Ethan Coen fall between these two stools. I’ve seen most all of the Coen brothers’ movies, and in nearly every case I had the same sequence of mixed feelings, not after the fact but on the spot. First came a rush of something like relief, usually within the first minute or two: whatever else Blood Simple, The Hudsucker Proxy, and Fargo were, they weren’t stupid. Thus reassured, I relaxed and started to enjoy myself–but then second thoughts started to creep in, not about how smart the Coens were, but about the ends to which their smartness was being put….

Read the whole thing here.

“People sometimes tell me that they prefer barbarism to civilisation. I doubt if they have given it a long enough trial. Like the people of Alexandria, they are bored by civilisation; but all the evidence suggests that the boredom of barbarism is infinitely greater.”

“People sometimes tell me that they prefer barbarism to civilisation. I doubt if they have given it a long enough trial. Like the people of Alexandria, they are bored by civilisation; but all the evidence suggests that the boredom of barbarism is infinitely greater.”

Kenneth Clark, script for Civilisation

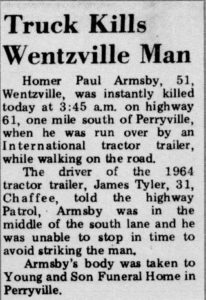

My posting about the sad fate of my beloved Uncle Paul, who vanished without trace from my life when I was a boy, brought me a fair amount of correspondence, including a note from a reader who was kind enough to e-mail me an electronic copy of something that I’d been unable to find on the web: the original newspaper story about Paul’s death.

Having written four biographies and a memoir, I’ve learned from hard experience how imperfect memories—my own included—can be. No matter how clear those memories may seem to be, primary sources have a way of sneaking up from behind and taking you by surprise. The story about Paul’s death that appeared in my hometown paper contained quite a few such surprises, starting with the fact that his full name was Homer Paul Armsby. To me, of course, he was “Uncle Paul” pure and simple, and I can’t recall anyone in my family ever calling him “Homer.”

Having written four biographies and a memoir, I’ve learned from hard experience how imperfect memories—my own included—can be. No matter how clear those memories may seem to be, primary sources have a way of sneaking up from behind and taking you by surprise. The story about Paul’s death that appeared in my hometown paper contained quite a few such surprises, starting with the fact that his full name was Homer Paul Armsby. To me, of course, he was “Uncle Paul” pure and simple, and I can’t recall anyone in my family ever calling him “Homer.”

Even more surprising to me was that Paul died in September of 1970, when I was fourteen years old. I last remember seeing him in 1966, and my brother, who is four years younger than me, barely remembers Paul at all. My best guess is that he paid his final visit to our house in Smalltown in 1967, though that’s only a guess. I’d wrongly supposed that he died shortly thereafter, but it appears instead that he moved to Wentzville, a town not far from St. Louis, and lived there on his own for a few years after his marriage to Aunt Suzy came to an end.

In all other particulars, my memory of Paul’s death is borne out by the bare facts that are recorded in the story: he was run over by a truck while walking in the middle of Highway 61 at a quarter to four in the morning. The rest is easy enough—too easy—to imagine.

My reader also sent me something even more surprising, a longer obituary published in an Arizona newspaper:

Mr. Armsby, a heavy equipment operator who formerly lived in Arizona three years, was killed in a vehicle accident Friday at Perryville, Mo. He was an Army veteran of World War II and a 32nd degree Mason in St. Louis. He was born in Corning, Ark.

It was news to me that Paul had lived in Arizona, much less that he had roots there. According to the obituary, he was survived by his parents, a brother, and three sisters, all of whom were living in the Phoenix area in 1970, as well as four other brothers and sisters who lived in Missouri. I wouldn’t be greatly surprised if one or two of his siblings are still alive, though I don’t intend to investigate further. Given the circumstances of his death, I can’t imagine that their memories of their brother are anything other than painful.

I’m glad, though, to know where Paul was laid to rest, for I had feared that he might possibly lie in an unmarked pauper’s grave. Not so: his body was returned to Arizona for burial in the Mountain View Cemetery of Mesa, an elaborately appointed institution reminiscent of Forest Lawn whose paths are lined with tall palm trees. My brother even managed to track down a photograph of the simple plaque that marks his grave, on which he is identified as “Homer P. Armsby,” a World War II vet. Since four other members of the Armsby family are buried in the same cemetery, it seems probable that there is no one left in Mesa to mourn him.

I’m glad, though, to know where Paul was laid to rest, for I had feared that he might possibly lie in an unmarked pauper’s grave. Not so: his body was returned to Arizona for burial in the Mountain View Cemetery of Mesa, an elaborately appointed institution reminiscent of Forest Lawn whose paths are lined with tall palm trees. My brother even managed to track down a photograph of the simple plaque that marks his grave, on which he is identified as “Homer P. Armsby,” a World War II vet. Since four other members of the Armsby family are buried in the same cemetery, it seems probable that there is no one left in Mesa to mourn him.

Shakespeare said it: What can we bequeath/Save our deposed bodies to the ground? But of course that isn’t quite true: most of us also leave behind memories, some good and others nightmarishly bad. A half-century after he was run over on Highway 61, I still remember Paul, and because he took great care never to let me see him in any other light, I think of him not as the unhappy man that he eventually became but as the sweet, kindly uncle who sang “You Are My Sunshine” to me when I was a little boy. I’m glad for that.

* * *

Jimmie Davis sings “You Are My Sunshine” in 1939:

Frank Sinatra sings “One for My Baby” at London’s Royal Festival Hall in 1962, accompanied by Bill Miller:

Mischa Elman plays Fritz Kreisler’s “Schön Rosmarin” on The Bell Telephone Hour, accompanied by Donald Voorhees and the Bell Telephone Orchestra. This episode was originally telecast by NBC on April 27, 1962:

Mischa Elman plays Fritz Kreisler’s “Schön Rosmarin” on The Bell Telephone Hour, accompanied by Donald Voorhees and the Bell Telephone Orchestra. This episode was originally telecast by NBC on April 27, 1962:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

An ArtsJournal Blog