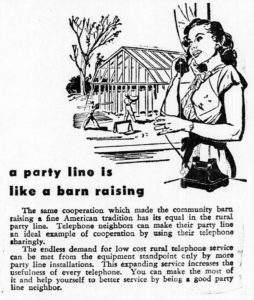

For all its increasingly aggressive incivility, I still get a fair amount of pleasure out of Twitter, enough so that I continue to take part in threads which amuse me sufficiently. Here’s a recent one: “Without revealing your actual age, what is something you remember that if you told a younger person, they wouldn’t understand?” This is a topic to which I’ve given much thought in the past, so it didn’t take much time for me to respond with “My grandmother had a party line.” I often wonder what viewers under the age of sixty make of the premise of Pillow Talk, the 1959 movie in which Rock Hudson and Doris Day play two strangers who share a Manhattan party line, though I dare say there are quite a few other things about Pillow Talk that confuse them even more.

For all its increasingly aggressive incivility, I still get a fair amount of pleasure out of Twitter, enough so that I continue to take part in threads which amuse me sufficiently. Here’s a recent one: “Without revealing your actual age, what is something you remember that if you told a younger person, they wouldn’t understand?” This is a topic to which I’ve given much thought in the past, so it didn’t take much time for me to respond with “My grandmother had a party line.” I often wonder what viewers under the age of sixty make of the premise of Pillow Talk, the 1959 movie in which Rock Hudson and Doris Day play two strangers who share a Manhattan party line, though I dare say there are quite a few other things about Pillow Talk that confuse them even more.

The deaths of Carrie Fisher and Debbie Reynolds led to an even more interesting thread: “What was the first celebrity death to really punch you in the gut?” I can just remember the day when President Kennedy was shot, but I was too young for his death to make an emotional impression on me. The murders of Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy took place five years later, by which time I had some appreciation of what it meant for two such men to have been shot down at a two-month interval. Even so, I was just twelve years old, still too young to grasp how consequential their deaths were. In any case, it’s not right to speak of the assassinations of King and the Kennedys as “celebrity deaths”: they were historical figures, not “celebrities,” and their deaths, like their lives, changed the world.

The first true “celebrity death” that made a significant impression on me was that of Michael Conrad, one of the stars of Hill Street Blues, a TV series that I watched faithfully every Thursday. Conrad died of cancer in 1983, four years into the run of the show, and his death was incorporated into a later episode. By then his character, Phil Esterhaus, seemed almost as familiar to me as a friend, in part because he and the other characters on the show were portrayed so vividly and intimately.

The first true “celebrity death” that made a significant impression on me was that of Michael Conrad, one of the stars of Hill Street Blues, a TV series that I watched faithfully every Thursday. Conrad died of cancer in 1983, four years into the run of the show, and his death was incorporated into a later episode. By then his character, Phil Esterhaus, seemed almost as familiar to me as a friend, in part because he and the other characters on the show were portrayed so vividly and intimately.

Since then, though, I can’t say that the death of any celebrity has “punched me in the gut.” Perhaps this is a function of the fact that I’ve now lived long enough to lose numerous real-life family members and intimate friends, something that was not yet the case in 1983. Whatever the reason, I was unresponsive to the outpouring of social-media sentiment that was triggered by the passing of (among others) Fisher, Reynolds, Edward Albee, Muhammad Ali, David Bowie, Leonard Cohen, George Michael, Prince, Alan Rickman, Garry Shandling, and Gene Wilder. Why should this be so? The reason, I think, is that while I admired some of these men and women, one or two greatly, I didn’t know any of them, nor did their lives and work shape my character or taste, as a good many of my (mostly) younger women friends claim to have been shaped by Carrie Fisher’s example.

This kind of detachment can offend those who partake fully of such feelings. I found that out when, eleven years ago, I wrote in this space about the death of Johnny Carson, in the process enraging many people who thought it inappropriate for me to coolly suggest that Carson’s fame would prove—as has indeed been the case—to be ephemeral.

None of this means that I’m incapable of grasping what it means to be moved by the death of a celebrity. On the night that Debbie Reynolds died, I watched Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo for the first time. I dislike most of Allen’s work, but I was touched to the heart by this particular film, in which Mia Farrow plays the part of an unhappily married waitress who goes to the movies in search of the emotional fulfillment that real life has failed to give her. I know how she felt. I see myself as a mostly happy person, yet one of the reasons why I immerse myself in the world of art is that it has the power to console me for the fearful trials of life. More than a few things have happened to me in my sixty years that I would have found hard to survive without such consolation, and I am profoundly grateful to the artists whose work has given it to me.

Nevertheless, there is for me an unbridgeable gap between admiration from a distance, however strong, and the more personal sentiment that for me is inextricably tied up with personal acquaintance. I had occasion last year to write The Wall Street Journal’s obituary for Brian Friel, a very great artist whom I never met in person but whose work spoke to me in a deeply personal way. Yet I can’t honestly say that I felt his death, at least not in the same way that I felt the death of, say, Jim Hall, another great artist whom I did know:

Nevertheless, there is for me an unbridgeable gap between admiration from a distance, however strong, and the more personal sentiment that for me is inextricably tied up with personal acquaintance. I had occasion last year to write The Wall Street Journal’s obituary for Brian Friel, a very great artist whom I never met in person but whose work spoke to me in a deeply personal way. Yet I can’t honestly say that I felt his death, at least not in the same way that I felt the death of, say, Jim Hall, another great artist whom I did know:

I knew him a bit, well enough to say hello after a gig, and I knew dozens of musicians who worked with him and esteemed him without limit. None of them ever had a bad word to say about him, at least not in my hearing. It goes without saying that not all great artists are good people, but Mr. Hall was by all accounts a genuinely kind and decent person, altogether admirable as a husband, father and colleague.

I don’t think a cold fish could have written that paragraph. Nor do I think that I was being insincere when I ended my online tribute to Brian Friel with this sentence: “The stage of the world feels empty this morning.” He meant something to me, something very big. But did I shed any tears for him? Not a one—even though I’ve wept more than once while watching his plays.

At any rate, that’s why I didn’t have anything to say about Carrie Fisher’s death, here or elsewhere. I thought she was a good actor and a good writer, and if you cried when she died, I wouldn’t dream of sneering at you for it. But one can only feel what one feels, and I felt nothing. That is, quite literally, just me.

* * *

The theatrical trailer for Pillow Talk, directed by Michael Gordon and starring Rock Hudson and Doris Day:

The last scene of Woody Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo, starring Mia Farrow: