“My final reflection, I’m afraid, was that if hypocrisy can be said to be the homage vice pays to virtue, theology could be said to be a homage nonsense tries to pay to sense.”

“My final reflection, I’m afraid, was that if hypocrisy can be said to be the homage vice pays to virtue, theology could be said to be a homage nonsense tries to pay to sense.”

James Gould Cozzens, By Love Possessed

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

On Tuesday afternoon I was sitting in the auditorium of Chicago’s Court Theatre, watching Charlie Newell reblock the final scene of his production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, which opens there on Saturday. Midway through the scene I received an e-mail from Eric Gibson, my editor at The Wall Street Journal. He informed me that “Sightings,” my biweekly Journal column about the arts, was being moved from Fridays to Thursdays, effective immediately, and asked me to stand by to read and approve the copyedited version of this week’s column, which would be arriving shortly via e-mail.

On Tuesday afternoon I was sitting in the auditorium of Chicago’s Court Theatre, watching Charlie Newell reblock the final scene of his production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, which opens there on Saturday. Midway through the scene I received an e-mail from Eric Gibson, my editor at The Wall Street Journal. He informed me that “Sightings,” my biweekly Journal column about the arts, was being moved from Fridays to Thursdays, effective immediately, and asked me to stand by to read and approve the copyedited version of this week’s column, which would be arriving shortly via e-mail.

Two minutes later my cellphone rang. It was Gordon Edelstein, who is in San Francisco remounting his production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, which opens next Wednesday at American Conservatory Theater. He and John Douglas Thompson wanted to know if they could change two words in the script.

As Gordon was reading the proposed change to me over the phone, I received a second e-mail from the Journal, this one containing my copyedited column. I started going through it as I listened to Gordon. Then, a minute or so later, I realized that someone in the auditorium was talking to me. It was Charlie, asking what I thought of a new music cue that he was trying out.

What about today? Well, I got up at five in the morning and went to Midway Airport. By the time you read these words, I’ll be somewhere between Chicago and New York, where a car will meet me at LaGuardia Airport and take me to the American Airlines Theatre to see a press preview of Noises Off. After the show I’ll go home and open my mail, then return to Broadway, where I’ll see a second press preview at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, this one of Our Mother’s Brief Affair, Richard Greenberg’s new play. I’ll have dinner with a friend after the show, then go back home, write my review of Noises Off for Friday’s Journal, and fall into bed.

What about today? Well, I got up at five in the morning and went to Midway Airport. By the time you read these words, I’ll be somewhere between Chicago and New York, where a car will meet me at LaGuardia Airport and take me to the American Airlines Theatre to see a press preview of Noises Off. After the show I’ll go home and open my mail, then return to Broadway, where I’ll see a second press preview at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, this one of Our Mother’s Brief Affair, Richard Greenberg’s new play. I’ll have dinner with a friend after the show, then go back home, write my review of Noises Off for Friday’s Journal, and fall into bed.

On Thursday morning I’ll get up at six, send in my Noises Off review, go to LaGuardia, and fly back to Midway, where a waiting car will drive me directly to the Court Theatre to attend the final rehearsal of Satchmo, which should be getting underway shortly after I arrive.

Yes, I know, I asked for it—but maybe not quite so much of it, and definitely not all at once.

* * *

W.C. Fields performs his vaudeville juggling act in The Old Fashioned Way, directed by William Beaudine and released in 1934:

Believe it or not, I don’t live in the past. No working journalist does, especially one with so many young friends. Even so, I do enjoy rummaging around in my well-stocked memory, and I don’t mind admitting that there are times when I prefer communing with the increasingly distant past to grappling with the uncomfortably proximate present. Ben Gazzara, Clifford Odets, Aaron Copland, Robert Warshow, even Jerry Lewis: today they all seem far more real to me than the pretty people I’d be reading about in Entertainment Weekly if I read Entertainment Weekly. No doubt this has something to do with my recent brush with mortality. To borrow a line from Patrick O’Brian, I’ve been a bar or two behind ever since I got out of the hospital, and though I’m sure I’ll catch up sooner or later, I find it oddly pleasant to linger among ghosts….

Read the whole thing here.

On Sunday I flew up to Chicago to see back-to-back preview performances of the Court Theatre’s all-new production of Satchmo at the Waldorf, directed by Charles Newell, which opens on Saturday. By then I’d seen several dozen performances of Satchmo’s previous iteration, the off-Broadway production directed by Gordon Edelstein that has also been mounted in Lenox, New Haven, Philadelphia, and Los Angeles and will be opening next Wednesday at San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater. It’d be hard to come up with two more dissimilar ways of staging the same show.

Gordon’s Satchmo, whose set was designed by Lee Savage, is for the most part naturalistic in approach. It takes place in a dressing room that is specifically intended to suggest a room at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, in whose Empire Room Louis Armstrong played his last gig in March of 1971, four months before his death. As part of his preparation for designing the set, Lee studied period photographs of the Waldorf, and he made every possible effort to create a performing space that has “Waldorf ” written all over it, right down to the tiniest of details. Armstrong’s dressing-room table is strewn with objects closely similar to the ones that can be seen in surviving photographs of his real-life dressing rooms and hotel rooms, and John Gromada, the sound designer, accompanied the production with a well-chosen selection of excerpts from Armstrong’s recordings. The goal was to make Satchmo look and sound as realistic as possible, and I think we succeeded. The sink even works!

Gordon’s Satchmo, whose set was designed by Lee Savage, is for the most part naturalistic in approach. It takes place in a dressing room that is specifically intended to suggest a room at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, in whose Empire Room Louis Armstrong played his last gig in March of 1971, four months before his death. As part of his preparation for designing the set, Lee studied period photographs of the Waldorf, and he made every possible effort to create a performing space that has “Waldorf ” written all over it, right down to the tiniest of details. Armstrong’s dressing-room table is strewn with objects closely similar to the ones that can be seen in surviving photographs of his real-life dressing rooms and hotel rooms, and John Gromada, the sound designer, accompanied the production with a well-chosen selection of excerpts from Armstrong’s recordings. The goal was to make Satchmo look and sound as realistic as possible, and I think we succeeded. The sink even works!

In a sense, Gordon’s straightforward, no-nonsense staging emanated from the design. Needless to say, the audience has to make a huge imaginative leap in order to “buy” the theatrical conceit of the play, in which a single actor switches back and forth without warning between Armstrong, Joe Glaser, and Miles Davis. But Lee’s set and Kevin Adams’ lighting plot underline every character change, and to date our audiences seem not to have any trouble keeping up with the action.

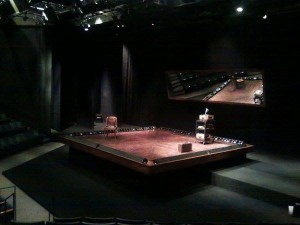

Charlie’s production of Satchmo, whose set was designed by John Culbert, is as expressionistic as Gordon’s production is naturalistic. It takes place on an elevated, all-but-bare playing area that is surrounded on all four sides by footlights. A huge upstage mirror is carefully positioned to reflect the onstage action in a way that is visible to everyone in the audience. Keith Parham’s sharp-angled lighting is unabashedly theatrical—his use of shadows is straight out of film noir—and Andre Pluess, the sound designer, has accompanied the show with a thickly layered mix of recordings by Armstrong, electronic music, and sound effects, some of them realistic and others almost hallucinatory. In a sense, the sound is the scenery: it hints at where we are and what is happening there.

Charlie’s production of Satchmo, whose set was designed by John Culbert, is as expressionistic as Gordon’s production is naturalistic. It takes place on an elevated, all-but-bare playing area that is surrounded on all four sides by footlights. A huge upstage mirror is carefully positioned to reflect the onstage action in a way that is visible to everyone in the audience. Keith Parham’s sharp-angled lighting is unabashedly theatrical—his use of shadows is straight out of film noir—and Andre Pluess, the sound designer, has accompanied the show with a thickly layered mix of recordings by Armstrong, electronic music, and sound effects, some of them realistic and others almost hallucinatory. In a sense, the sound is the scenery: it hints at where we are and what is happening there.

Do I prefer one version over the other? No. Both productions seem to me to be completely and equally valid, each in its own way. I wouldn’t want to have choose between them—and I don’t have to choose. As soon as we open Charlie’s Satchmo in Chicago, I’ll fly out to San Francisco to open Gordon’s Satchmo. I’m thrilled at the prospect of the juxtaposition.

To be sure, my personal taste runs more to the poetic abstraction of lyric theater, and Charlie’s Satchmo is poetic—and beautiful—beyond anything I could possibly have imagined. But I also adore smell-the-coffee kitchen-sink realism when it’s done well, and Gordon and his design team did it really, really well. As my Louis Armstrong says when describing the introductory trumpet cadenza of “West End Blues,” by the time you get to the end of their version of the show, “you know you done been somewhere.”

All this is of particular relevance to me because I’ll be directing my own production of Satchmo at Palm Beach Dramaworks later this year. I’ve spent a lot of time talking to Michael Amico, the set designer, about how we want our Satchmo to look, and he e-mailed me his first preliminary sketch of the set on Saturday. Our plan at present is to split the difference, so to speak, between Gordon and Charlie: the Palm Beach Satchmo will be naturalistic, but in a looser, less historically specific way.

All this is of particular relevance to me because I’ll be directing my own production of Satchmo at Palm Beach Dramaworks later this year. I’ve spent a lot of time talking to Michael Amico, the set designer, about how we want our Satchmo to look, and he e-mailed me his first preliminary sketch of the set on Saturday. Our plan at present is to split the difference, so to speak, between Gordon and Charlie: the Palm Beach Satchmo will be naturalistic, but in a looser, less historically specific way.

And how well will that work? Your guess is as good as mine. But I do know that whatever its ultimate value as a play, Satchmo at the Waldorf has so far proved strong enough to have inspired two full-scale productions that are radically different in appearance and approach, as well as a small-scale version, the 2011 Orlando premiere, that was directed by Rus Blackwell and designed by William Elliot. Staged in a tiny cabaret-style black-box theater, the first Satchmo presented the show in a much more intimate (but similarly convincing) manner.

And how well will that work? Your guess is as good as mine. But I do know that whatever its ultimate value as a play, Satchmo at the Waldorf has so far proved strong enough to have inspired two full-scale productions that are radically different in appearance and approach, as well as a small-scale version, the 2011 Orlando premiere, that was directed by Rus Blackwell and designed by William Elliot. Staged in a tiny cabaret-style black-box theater, the first Satchmo presented the show in a much more intimate (but similarly convincing) manner.

Am I a good enough director to find a fourth, comparably persuasive way to thread the needle? We’ll see. The mere fact that I wrote the play, though, is no guarantee that I have anything original to say about it as a director, nor do I think that my interpretation of Satchmo must necessarily be “right.” The author doesn’t always know best! So when I go down to Palm Beach to stage the show, I intend to approach the script as if it had been written by another person. Insofar as possible, I want to try to see it fresh.

Between them, Gordon, Charlie, Rus, and their respective design teams have now taught me a vast amount about unearthing the directorial possibilities in a play. The rest is up to Michael and me.

* * *

Hearst Metrotone News’ Louis Armstrong obituary, released in 1971. This featurette contains what is thought to be the only surviving film footage shot at Armstrong’s last gig at the Waldorf-Astoria, as well as scenes from his funeral in New York, at which Peggy Lee sang “The Lord’s Prayer.” The eulogy was delivered by Fred Robbins:

The final dress rehearsal for the first preview of the Court Theatre’s production of Satchmo at the Waldorf took place in Chicago last Thursday night…and I wasn’t there. I was in Florida, reviewing another show. Granted, I flew up three days later, but it still felt strange to be somewhere else on Thursday. I was, after all, intimately involved in the rehearsal process for all six of the show’s previous productions, and I spent two very intense weeks working on Satchmo in Chicago last month.

The final dress rehearsal for the first preview of the Court Theatre’s production of Satchmo at the Waldorf took place in Chicago last Thursday night…and I wasn’t there. I was in Florida, reviewing another show. Granted, I flew up three days later, but it still felt strange to be somewhere else on Thursday. I was, after all, intimately involved in the rehearsal process for all six of the show’s previous productions, and I spent two very intense weeks working on Satchmo in Chicago last month.

From here on out, though, my presence will be strictly optional. I’m flying to San Francisco next Monday to open American Conservatory Theatre’s staging of Satchmo, but that one is a straight remounting of the 2014 off-Broadway version. I don’t need to help with rehearsals: I’ll be there strictly to publicize the production, and when it transfers to Colorado Springs in February, I won’t be going with it. Indeed, I won’t even be seeing Seacoast Repertory Theatre’s all-new production, which opens in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, on January 22. All I’ll get to do is read about it.

Why am I not traveling to Colorado Springs and Portsmouth to see Satchmo? Because I have a day job, one that requires me to see shows in New York and all over the country, then review them each Friday in The Wall Street Journal. I was able to take two full weeks off to rehearse in Chicago solely because of the peculiarities of the 2015 calendar (the Journal doesn’t publish on Christmas or New Year’s Day, both of which fell on a Friday this past year). In order to shoehorn the Chicago and San Francisco productions into my calendar while simultaneously covering Broadway openings in January, I’ll have to spend the next couple of weeks doing an inordinate amount of cross-country flying. After that, though, it’s back to business.

Fortunately for me, I love the “business” of being a drama critic, so none of this is to be construed as a complaint. Nor do I care to be away from Mrs. T for longer than absolutely necessary, much less to stash her on the Gulf of Mexico for eleven days while I bounce around the colder parts of America.

The real problem, I think, is that I can’t quite grasp that Satchmo has—and, I hope, will continue to have—a life without me. Yes, I did my best to be helpful to Charlie Newell and Barry Shabaka Henley, the director and star of the Court Theater’s production of Satchmo, but I know that the Court could have produced the show perfectly well had I stayed home. Once we opened in New York in 2014 and I signed off on the published version of the text, my job was done. For better or worse, Satchmo at the Waldorf is now on its own.

The real problem, I think, is that I can’t quite grasp that Satchmo has—and, I hope, will continue to have—a life without me. Yes, I did my best to be helpful to Charlie Newell and Barry Shabaka Henley, the director and star of the Court Theater’s production of Satchmo, but I know that the Court could have produced the show perfectly well had I stayed home. Once we opened in New York in 2014 and I signed off on the published version of the text, my job was done. For better or worse, Satchmo at the Waldorf is now on its own.

The truth is that I went to Chicago mostly to watch Charlie work. As regular readers of this space know, I’m staging my own production of Satchmo at the Waldorf in West Palm Beach later this year. It’ll be my professional directing debut, and the more I learn about the process before waltzing into the rehearsal hall in April, the more smoothly things will go. I can’t think of a better way to learn than to watch Charlie, just as I watched Rus Blackwell and Gordon Edelstein when Satchmo was first produced in Orlando and Lenox.

I won’t deny, though, that I also went to Chicago just for the fun of it. My three operatic collaborations with Paul Moravec taught me that there are few things in the world more purely pleasurable than rehearsing a show, and having finally gotten around to writing a play on the eve of my late middle age, I’m well aware that I won’t get anything remotely approaching an unlimited number of opportunities to repeat the experience. That being the case, I figure I’d better squeeze all the juice I can out of this one. Nobody has to tell me that the clock is running.

I won’t deny, though, that I also went to Chicago just for the fun of it. My three operatic collaborations with Paul Moravec taught me that there are few things in the world more purely pleasurable than rehearsing a show, and having finally gotten around to writing a play on the eve of my late middle age, I’m well aware that I won’t get anything remotely approaching an unlimited number of opportunities to repeat the experience. That being the case, I figure I’d better squeeze all the juice I can out of this one. Nobody has to tell me that the clock is running.

So I’m flying from Chicago to New York on Wednesday, from New York to Chicago on Thursday, from Chicago to San Francisco next Monday, and from San Francisco back to Sanibel Island next Thursday. That part won’t be even slightly fun—but what happens in between will be worth it.

* * *

Barry Shabaka Henley, the star of the Court Theatre’s Chicago premiere of Satchmo at the Waldorf, talks about his belated discovery of Louis Armstrong:

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||

An ArtsJournal Blog