“In truth, poverty is an anomaly to rich people: it is very difficult to make out why people who want dinner do not ring the bell.”

“In truth, poverty is an anomaly to rich people: it is very difficult to make out why people who want dinner do not ring the bell.”

Walter Bagehot, “The Waverley Novels”

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

I love aphorisms and epigrams, perhaps because I have no gift for coining them. The brilliantly precise concision that allows writers like La Rochefoucauld, Chamfort, and Karl Kraus to say big things on the smallest possible scale, and the discipline of mind that enables it, simply don’t come naturally to me.

For this reason, it’s always a joy for me to encounter a previously unknown aphorist (to me, anyway). George Weigel wrote a piece last week in which he had occasion to quote George Savile, the First Marquess of Halifax, a seventeenth-century British statesman of whose long career I knew nothing. In addition to being a politician of note, Savile was also a writer with a knack for terseness. Weigel points out that he “ranks second only to the immortal Dr. Johnson in the number of entries in The Viking Book of Aphorisms.” I own that book and consult it often, but for some reason Savile’s name had escaped my notice.

I did a bit of nosing around the web and found that Savile’s aphorisms were collected in 1750 in a volume called Political, Moral and Miscellaneous Thoughts and Reflections. I promptly sifted through it and culled the following observations, which I hope you’ll find as striking as I did:

I did a bit of nosing around the web and found that Savile’s aphorisms were collected in 1750 in a volume called Political, Moral and Miscellaneous Thoughts and Reflections. I promptly sifted through it and culled the following observations, which I hope you’ll find as striking as I did:

• “Our vices and virtues couple with one another, and get children that resemble both their parents.”

• “Anger is never without an argument, but seldom with a good one.”

• “One should no more laugh at a contemptible fool than at a dead fly.”

• “The memory of an enemy admitteth no decay but age.”

• “Weak men are apt to be cruel, because they stick at nothing that may repair the ill-effect of their mistakes.”

• “Mistaken kindness is little less dangerous than premeditated malice.”

• “Explaining is generally half-confessing.”

• “A long vindication is seldom a skilful one.”

• “The world is nothing but vanity cut out into several shapes.”

• “Were it not for bunglers in the manner of doing it, hardly any man would ever find out he was laughed at.”

• “The reading of most men is like a wardrobe of old clothes that are seldom used.”

• “It is some kind of scandal not to bear with the faults of an honest man.”

• “All are apt to shrink from those that lean upon them.”

One of Garner’s albums was called The Most Happy Piano, and that sums him up very nicely. As Joseph Epstein wrote of H.L. Mencken, “He achieves his effect through the magical transfer of joie de vivre.” You simply cannot listen to his best recordings without breaking out in an ear-to-ear grin. What’s more, Garner was by all accounts as likable as the music he made. As George Avakian, his producer at Columbia, recalled, “He was really like a pixie or an elf. When you split with Erroll at the end of an evening you left with a happy smile and a good feeling. No worries at all. Off to bed feeling great. That’s what Erroll did for people.”…

Read the whole thing here.

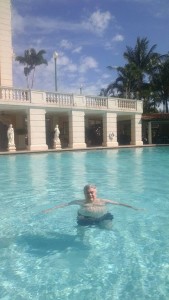

I turned sixty on Saturday. Mrs. T and I didn’t throw a party, though. That might have been fun, but we were staying at Florida’s Biltmore Hotel, which is surely enough of a celebration for any reasonable person, and we don’t know anybody who lives in Coral Gables.

I turned sixty on Saturday. Mrs. T and I didn’t throw a party, though. That might have been fun, but we were staying at Florida’s Biltmore Hotel, which is surely enough of a celebration for any reasonable person, and we don’t know anybody who lives in Coral Gables.

Instead of having a couple of dozen friends over to mark the occasion, I spent the morning reading “Calvin and Hobbes” strips,, my latest enthusiasm. Then we went downstairs, ate a late and leisurely brunch consisting mainly of fresher-than-fresh fruit, and sat in the sun by the Biltmore’s famous pool, where I heard a bossa-nova cover version of “Jumpin’ Jack Flash” that made me giggle, though I actually rather liked it. Except for taking a single theater-related phone call at poolside, I did no work of any kind. In the evening we had a very nice dinner at Fontana, and that was that.

Turning sixty, I’m told, is a big deal. I can’t say that it feels especially big, though, nor do I feel nearly as old as I am, save on the too-frequent occasions when I have trouble pulling a name out of my hat. (I’ve reached the time of life when I forget the names of old friends who are standing next to me, waiting patiently to be introduced to new ones.) George Bernard Shaw said it: “Any fool can be 60 if he lives long enough.”

It was a much bigger deal when I turned fifty. Not only had I come perilously close to dying just two months earlier, but I met the woman who became Mrs. T right around the same time. Everything that has happened to me since then is an outgrowth of those two encounters, the first with the imminent prospect of death and the second with the possibility of the more abundant life that I am now privileged to live for as long as it lasts.

How should I spend whatever is left of it? Cardinal Newman warns us to “use well the interval,” the unknown amount of time that separates every man from his inescapable appointment with the Distinguished Thing. In an attempt to take stock, I looked up what I wrote in this space on my fiftieth birthday, and found these words:

How should I spend whatever is left of it? Cardinal Newman warns us to “use well the interval,” the unknown amount of time that separates every man from his inescapable appointment with the Distinguished Thing. In an attempt to take stock, I looked up what I wrote in this space on my fiftieth birthday, and found these words:

So what do I do next? Like many people, my life has been a series of goals, a things-to-do list, and at fifty I now find myself in the position, at once pleasing and disconcerting, of having accomplished most of them. As for the things I haven’t yet done, nearly all of them are things I’m no longer likely to do, assuming I ever was: I doubt, for instance, that I’ll learn a second language or write a novel or become a father. I could spend the rest of my life running in place, and I suppose that would be perfectly fine. Except that I know it wouldn’t. The time will come, if it hasn’t already, when I’ll want to try my hand at something new—and I haven’t the slightest idea what it might be.

Well, I didn’t learn a second language or write a novel or become a father, but I did do plenty of other unexpected things, the most surprising of which was that I started writing for the stage. Indeed, Dramatists Play Service, the publishers of Satchmo at the Waldorf, informed me last month that my first play is now tied for tenth place on its its Top Professional Licenses list. Satchmo, in other words, has become something of a hit.

As for meeting and marrying Mrs. T, I can’t begin to tell you what that has meant to me, so I won’t even try. Suffice it to say that I wouldn’t have dared to write Satchmo, much less The Letter, without the continuing inspiration of her presence. She is everything to me.

So…what do I do next?

Regular readers of this blog know the obvious answer to that question: I’ll be making my professional directing debut in May with Palm Beach Dramaworks’ production of Satchmo at the Waldorf. That’s a pretty unusual thing for a sixty-year-old man to do, and I can’t wait to plunge head first into the next chapter of my brand-new part-time career.

Regular readers of this blog know the obvious answer to that question: I’ll be making my professional directing debut in May with Palm Beach Dramaworks’ production of Satchmo at the Waldorf. That’s a pretty unusual thing for a sixty-year-old man to do, and I can’t wait to plunge head first into the next chapter of my brand-new part-time career.

Right now, though, I’m more than content to sit in the sunshine, hit my deadlines, and think about how I want Satchmo to look and sound on stage when May 13 rolls around. Beyond that, I have no plans, and for the moment I don’t really feel that I need any. I suppose I could spend the rest of my life running in place, but I’m pretty sure I won’t. And if such should prove to be my fate, then at least I’ll be running in tandem—which is, after all, what matters most.

* * *

The last scene of The Candidate, a 1972 film directed by Michael Ritchie, written by Jeremy Larner, and starring Robert Redford, Peter Boyle, and Melvyn Douglas:

Jimmy Durante sings “September Song” on The Jimmy Durante Show. The song is from the score of Knickerbocker Holiday, by Maxwell Anderson and Kurt Weill. This episode was originally telecast on July 9, 1955:

Jimmy Durante sings “September Song” on The Jimmy Durante Show. The song is from the score of Knickerbocker Holiday, by Maxwell Anderson and Kurt Weill. This episode was originally telecast on July 9, 1955:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.)

“Memory is a great artist, we are told; she selects and rejects and shapes and so on. No doubt. Elderly persons would be utterly intolerable if they remembered everything. Everything, nevertheless, is just what they themselves would like to remember, and just what they would like to tell to everybody.”

“Memory is a great artist, we are told; she selects and rejects and shapes and so on. No doubt. Elderly persons would be utterly intolerable if they remembered everything. Everything, nevertheless, is just what they themselves would like to remember, and just what they would like to tell to everybody.”

Max Beerbohm, “No. 2, The Pines” (courtesy of Levi Stahl)

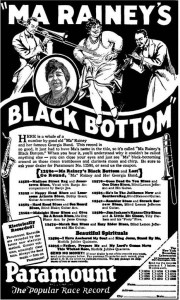

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I review a show in Sarasota, Florida, Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe’s revival of August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

In today’s Wall Street Journal drama column I review a show in Sarasota, Florida, Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe’s revival of August Wilson’s Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom.

I also take note of the off-Broadway remount of Bedlam’s 2014 stage version of Jane Austen’s Sense & Sensibility, which I called “by far the smartest Jane Austen adaptation to come along since Amy Heckerling’s Clueless, and at least as much fun,” when I originally reviewed it in the Journal.

Here’s an excerpt.

* * *

August Wilson’s ten “Pittsburgh Cycle” plays, in which he chronicled the black experience in America, haven’t been done nearly often enough in New York since his death in 2005. Only three of them have ever been revived on Broadway. Fortunately, they long ago became staple items in the repertories of America’s regional theaters, and I seek them out whenever I’m on the road. That’s what brought me back to Westcoast Black Theatre Troupe, a Florida company that performs black-themed musicals and plays for a largely white audience (Sarasota County, its home base, is only 4% black). I liked what Westcoast Black did with Charles Smith’s “Knock Me a Kiss” last January, and I’m even more impressed by its version of “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” Wilson’s 1984 history play about a real-life blues singer of the Twenties (played by Tarra Conner Jones) who outlived her popularity. This small-scale staging, directed by Chuck Smith and performed in the company’s black-box theater, is one of the best-acted Wilson revivals I’ve seen in recent seasons, and the acting gains in impact from being viewed in so compact a space….

Not much seems to happen in “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” until the end of the evening. Rainey and her band (Robert Douglas, Kenny Dozier, Patric Robinson and Henri Watkins) come to a dingy recording studio in Chicago to cut a few tunes. The musicians arrive early, sit around the rehearsal room, swap stories and share a joint. At length Rainey and her entourage show up. After a snarling who’s-in-charge-here skirmish with her manager (Stephen Emery) and the producer of the session (Terry Wells), both of whom are white, Rainey finally gets down to business, makes the records and stalks out. That’s when the bomb goes off…

Not much seems to happen in “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” until the end of the evening. Rainey and her band (Robert Douglas, Kenny Dozier, Patric Robinson and Henri Watkins) come to a dingy recording studio in Chicago to cut a few tunes. The musicians arrive early, sit around the rehearsal room, swap stories and share a joint. At length Rainey and her entourage show up. After a snarling who’s-in-charge-here skirmish with her manager (Stephen Emery) and the producer of the session (Terry Wells), both of whom are white, Rainey finally gets down to business, makes the records and stalks out. That’s when the bomb goes off…

You can’t write a play in this way without a preternaturally keen ear, and Wilson’s ability to quarry glittering nuggets of folk poetry out of the everyday speech of common men (“Levee would complain if a gal ain’t laid across his bed just right”) remains unrivaled. But you can’t stage such a play effectively without actors who can deliver the dialogue in a completely spontaneous-sounding way—and a director who knows how to weld them together into a true ensemble. In this production, Mr. Smith and his cast have hit the high C of absolute authenticity….

* * *

To read my review of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, go here.

To read my original review of Sense & Sensibility, go here.

Ma Rainey’s 1927 Paramount recording of “‘Ma’ Rainey’s Black Bottom.” The session that produced this 78 side is portrayed in August Wilson’s play:

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

| 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

| 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 |

| 28 | 29 | 30 | ||||

An ArtsJournal Blog