“We spend our lives fighting to get people very slightly more stupid than ourselves to accept truths that the great men have always known.”

“We spend our lives fighting to get people very slightly more stupid than ourselves to accept truths that the great men have always known.”

Doris Lessing, The Golden Notebook

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

The trouble is that striking balances doesn’t come naturally to me. I’m a head-first guy, an enthusiast who jumps first and looks on the way down. Right now I’m not doing enough. Next month I may be doing too much. Somewhere in between manic activity and paralytic passivity lies the point of equipoise that I seek—in vain, of course. Equipoise is for teeter-totters. Real life is full of earthquakes….

Read the whole thing here.

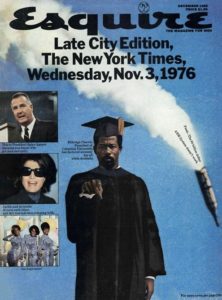

One of my favorite bloggers reminds me that in December of 1969, Esquire invited twenty-five venerable celebrities to offer end-of-the-decade advice, most of it predictably platitudinous, to the magazine’s younger readers. Among the invitees, I rejoice greatly to report, was Louis Armstrong, who wrapped up his contribution to the symposium as follows:

One of my favorite bloggers reminds me that in December of 1969, Esquire invited twenty-five venerable celebrities to offer end-of-the-decade advice, most of it predictably platitudinous, to the magazine’s younger readers. Among the invitees, I rejoice greatly to report, was Louis Armstrong, who wrapped up his contribution to the symposium as follows:

Just want to say that music has no age. Most of your great composers—musicians—are elderly people, way up there in age—they will live forever. There’s no such thing as on the way out. As long as you are doing something interesting and good. You are in business as long as you are breathing. “Yeah.”

Very nice—and, as always, utterly characteristic.

What interests me more about the piece, though, is the list of contributors. In addition to Armstrong, it included:

Harry J. Anslinger

Avery Brundage

Lady Olave Baden-Powell

Cass Canfield

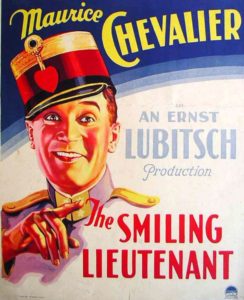

Maurice Chevalier

Buckminster Fuller

Lillian Gish

Rube Goldberg

Ernest Gruening

Lewis B. Hershey

Urho Kekkonen

Arthur Krock

Lotte Lehmann

Raymond Loewy

J.B. Rhine

Hyman G. Rickover

Norman Rockwell

Robb Sagendorph

Leverett Saltonstall

Ted Shawn

Edward Steichen

Leopold Stokowski

Harold C. Urey

King Vidor

My question is this: how many of those names do you recognize?

I knew twenty of them, but I’m sixty years old and passably well-informed, and Google and Wikipedia soon set me straight on Lady Baden-Powell and Messrs. Kekkonen, Rhine, Sagendorph, and Urey, all of whom struck me as quite worth remembering, though I’m not blushing at having come up short on their names. I couldn’t help but wonder, though, what the average score of a forty-year-old American would be—and how many more of Esquire’s now-deceased symposiasts will be totally forgotten ten years from today.

Rube Goldberg is already pretty far gone, enough so that it seems fair to call the still-common expression “Rube Goldberg machine” a stone-dead metaphor, while Maurice Chevalier, who used to be a name-above-the-title star, is now remembered by most people only for his appearance in Gigi. Will his name ring any bells at all come 2026? Or will he have gone the way of Lillian Gish and Hyman Rickover?

Rube Goldberg is already pretty far gone, enough so that it seems fair to call the still-common expression “Rube Goldberg machine” a stone-dead metaphor, while Maurice Chevalier, who used to be a name-above-the-title star, is now remembered by most people only for his appearance in Gigi. Will his name ring any bells at all come 2026? Or will he have gone the way of Lillian Gish and Hyman Rickover?

Posthumous fame is a fragile thing, of course, and now that the teaching of history has fallen to pieces, it grows more fragile still. I read last week that a fifth of all British teenagers believe Winston Churchill to have been a fictional character, whereas 47% believe that Eleanor Rigby was real. Needless to say, there is ever and always ample reason to despair, and my Despair-O-Meter came close to breaking last week for other, arguably better reasons. Still, anyone who thinks that Winston Churchill wasn’t a real person is, not to put too fine a point on it, an idiot—which suggests that we really are living in what Mike Judge calls an idiocracy.

All this notwithstanding, I continue to cling faithfully to the belief that most people will still know who Satchmo was come 2026. But I’m not sure how much of the rent I’d bet on it.

* * *

The trailer for Idiocracy:

Something for Nothing, a 1940 General Motors promotional film featuring Rube Goldberg:

Continuo, a ballet by Antony Tudor set to Pachelbel’s Canon and performed by the Paris Opera Ballet in 1985. The dancers are Sylvie Guillem, Laurent Hilaire, Isabelle Guérin, Manuel Legris, Clotilde Vayer, and Herve Dirmann. This ballet was made by Tudor in 1971 specifically for performance by students and smaller dance companies. It was commissioned by the National Endowment for the Arts:

Continuo, a ballet by Antony Tudor set to Pachelbel’s Canon and performed by the Paris Opera Ballet in 1985. The dancers are Sylvie Guillem, Laurent Hilaire, Isabelle Guérin, Manuel Legris, Clotilde Vayer, and Herve Dirmann. This ballet was made by Tudor in 1971 specifically for performance by students and smaller dance companies. It was commissioned by the National Endowment for the Arts:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“An Orwellian world is much easier to recognize, and to oppose, than a Huxleyan. Everything in our background has prepared us to know and resist a prison when the gates begin to close around us. We are not likely, for example, to be indifferent to the voices of the Sakharovs and the Timmermans and the Walesas. We take arms against such a sea of troubles, buttressed by the spirit of Milton, Bacon, Voltaire, Goethe and Jefferson. But what if there are no cries of anguish to be heard? Who is prepared to take arms against a sea of amusements? To whom do we complain, and when, and in what tone of voice, when serious discourse dissolves into giggles? What is the antidote to a culture’s being drained by laughter?”

“An Orwellian world is much easier to recognize, and to oppose, than a Huxleyan. Everything in our background has prepared us to know and resist a prison when the gates begin to close around us. We are not likely, for example, to be indifferent to the voices of the Sakharovs and the Timmermans and the Walesas. We take arms against such a sea of troubles, buttressed by the spirit of Milton, Bacon, Voltaire, Goethe and Jefferson. But what if there are no cries of anguish to be heard? Who is prepared to take arms against a sea of amusements? To whom do we complain, and when, and in what tone of voice, when serious discourse dissolves into giggles? What is the antidote to a culture’s being drained by laughter?”

Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business

In today’s Wall Street Journal I review the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival’s new production of Measure for Measure. Here’s a review.

* * *

Why do some of Shakespeare’s plays get produced more often than others? For all the self-evidently surpassing excellence of the most familiar masterpieces, I’m tempted to say that the answer in many cases is sheer force of habit. On the other hand, certain of the less popular plays really are less popular for a reason—though it’s not that they’re less good. When it comes to the plays known to scholars as “problem plays,” which teeter uncomfortably but purposefully between low comedy and high tragedy, it isn’t hard to see why cautious directors might choose to play safe and stick to “Hamlet.”

Not so Davis McCallum, artistic director of the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival. After two seasons at the helm, he looks to be personally drawn to the trickier plays. Mr. McCallum directed “The Winter’s Tale” last summer, and this time around he’s giving us a production of “Measure for Measure,” the quintessential problem play, that’s staged and acted so passionately that you’ll come away saying “No problem!”…

Not so Davis McCallum, artistic director of the Hudson Valley Shakespeare Festival. After two seasons at the helm, he looks to be personally drawn to the trickier plays. Mr. McCallum directed “The Winter’s Tale” last summer, and this time around he’s giving us a production of “Measure for Measure,” the quintessential problem play, that’s staged and acted so passionately that you’ll come away saying “No problem!”…

Save for the use of festive modern dress and a touch of gender-switching non-traditional casting, he sticks to playing “Measure for Measure” down the center, trusting the audience to accept its complexities as true to life—which they are and which we do, happily. If you’ve ever been tempted to laugh at a funeral, you’ll know where Shakespeare is coming from, and Mr. McCallum gets it.

No small part of the excellence of this “Measure for Measure” is due to Ms. Purcell, who has impressed me no end in regional productions of such demanding fare as Samuel Beckett’s “Play” (at San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theater in 2012) and Tom Stoppard’s “The Real Thing” (at Studio Theatre of Washington, D.C., in 2014). Her Isabella is so intense that you can all but see her quivering with barely contained passion. It makes no sense that an actor capable of such things isn’t much better known….

* * *

Read the whole thing here.

The trailer for Measure for Measure:

Orson Welles talks about Falstaff, makes himself up in front of the studio audience, and performs a monologue from the second part of Henry IV on The Dean Martin Show. This episode was originally telecast by NBC on September 26, 1968:

Orson Welles talks about Falstaff, makes himself up in front of the studio audience, and performs a monologue from the second part of Henry IV on The Dean Martin Show. This episode was originally telecast by NBC on September 26, 1968:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |||||

| 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 |

| 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 |

| 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 |

| 31 | ||||||

An ArtsJournal Blog