“One of the most disconcerting, unpleasant, and sordid aspects of life is the awareness that nearly all of us find an evil deed more exciting than a good one.”

“One of the most disconcerting, unpleasant, and sordid aspects of life is the awareness that nearly all of us find an evil deed more exciting than a good one.”

Josep Pla, The Gray Notebook (trans. Peter Bush)

Terry Teachout on the arts in New York City

If my family had any dark secrets, they went to the grave with my parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. But like all families, we did have a few subjects of which we preferred not to speak save in hushed tones, foremost among them the fate of my Uncle Paul.

Paul ran a service station and, later on, sold used cars. He was a beloved and trusted figure of my boyhood, so much so that I would spend the night with him and Aunt Suzy, my mother’s sister, on the rare occasions when my parents went out of town together. I remember him as a warm, affectionate man who taught me how to sing “You Are My Sunshine” and “How Dry I Am” (a grimly ironic choice of tunes, given what happened to him) and play shuffleboard (he’d painted a court on the floor of his basement). But Paul disappeared from my life in the mid-Sixties, and the only thing my parents told me at the time was that he and Suzy had gotten a divorce, an occurrence that was all but unthinkable among my mother’s people, who were the most devout of small-town churchgoers.

Paul ran a service station and, later on, sold used cars. He was a beloved and trusted figure of my boyhood, so much so that I would spend the night with him and Aunt Suzy, my mother’s sister, on the rare occasions when my parents went out of town together. I remember him as a warm, affectionate man who taught me how to sing “You Are My Sunshine” and “How Dry I Am” (a grimly ironic choice of tunes, given what happened to him) and play shuffleboard (he’d painted a court on the floor of his basement). But Paul disappeared from my life in the mid-Sixties, and the only thing my parents told me at the time was that he and Suzy had gotten a divorce, an occurrence that was all but unthinkable among my mother’s people, who were the most devout of small-town churchgoers.

Paul came to our house a couple of years later for a very brief nighttime visit about which I recall nothing but the fact that it took place. If memory serves, my brother and I had already been put to bed when he unexpectedly showed up on the doorstep, and our parents didn’t get us up to see him. A few weeks after that, he was run over by a truck and killed.

My mother then told me that Paul had been an alcoholic, and that he’d stayed away from my brother and me because he didn’t want us to see what had become of him. It was the first time I’d heard the word “alcoholic,” and she had to explain to me what it meant. Suzy, she said, had left him because of his drinking, then came back when he started going to AA meetings. But he couldn’t stay sober, and when she left him again, it was for keeps. My mother said that he’d gotten drunk and wandered into the path of an oncoming truck, and she left me with the impression that she thought he’d done it deliberately.

Paul was the first person to die to whom I was close, and his death left a deep mark on my psyche. I suspect it’s the main reason why I’ve never been much of a drinker. But while my mother always spoke of him with fondness, the other members of the family never mentioned Paul again except when prompted. Some of them, I’m sure, were ashamed of him, for in those days it was widely taken for granted that alcoholism was not a disease but a moral weakness, and those who succumbed to it were viewed with contempt.

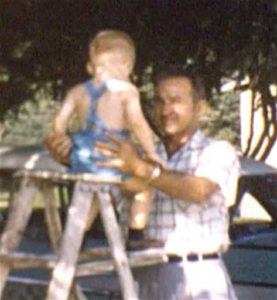

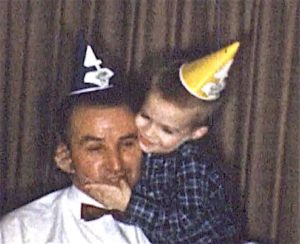

So far as I can recall, I’ve never seen a still picture of Paul, but he does appear in two of the home movies that my father shot between 1956 and 1966 and that my brother sent to me last week as a Christmas present. In the first scene, he is standing behind a ladder in the driveway of my grandmother’s home, watching as I climb to the top rung, then taking me in his arms. In the second, he is sitting beside me at my fourth birthday party. The love that we felt for one another is plain to see in both clips.

So far as I can recall, I’ve never seen a still picture of Paul, but he does appear in two of the home movies that my father shot between 1956 and 1966 and that my brother sent to me last week as a Christmas present. In the first scene, he is standing behind a ladder in the driveway of my grandmother’s home, watching as I climb to the top rung, then taking me in his arms. In the second, he is sitting beside me at my fourth birthday party. The love that we felt for one another is plain to see in both clips.

Seeing Paul after so many years made me wonder whether I might be able to find out anything more about him on the Web. I Googled his name, and this short newspaper piece, originally published in the Cape Girardeau Southeast Missourian in 1958, popped up:

Paul Armsby, owner of Paul’s 66 Service Station at 340 S. Sprigg St., has received a $50 award from the Phillips Petroleum Co., for giving perfect driveway service to a Phillips “mystery motorist.” In the picture he is shown at the left receiving the award from D.V. Shaner, district salesman. Others in the picture at the left are station attendants, Don Hency and Richard Gerlach.

Beyond that…nothing. Paul and Suzy had no children, and I don’t know whether any members of his own family are alive. He seems to have been born in Arkansas in 1919 or 1920, but I can find no record of his death, nor was an obituary published in any of the local newspapers. Save for that lone paragraph in the Southeast Missourian, it’s as though he’d never existed. I don’t even know where he’s buried. I greatly regret to say that I made no mention of him in the memoir of my childhood that I published in 1991, mainly because I wanted to spare Suzy’s feelings (she had not yet died when the book came out).

Beyond that…nothing. Paul and Suzy had no children, and I don’t know whether any members of his own family are alive. He seems to have been born in Arkansas in 1919 or 1920, but I can find no record of his death, nor was an obituary published in any of the local newspapers. Save for that lone paragraph in the Southeast Missourian, it’s as though he’d never existed. I don’t even know where he’s buried. I greatly regret to say that I made no mention of him in the memoir of my childhood that I published in 1991, mainly because I wanted to spare Suzy’s feelings (she had not yet died when the book came out).

I find it unutterably sad that my Uncle Paul has vanished almost without trace. It puts me in mind of something that H.L. Mencken wrote in 1927:

I have done a great deal less than I wanted to do and a great deal less than I might have done if my equipment had been better, but this, at least, I have accomplished, and it is one of the principal desires of man: I have delivered myself from anonymity.

Like most of the rest of us, Paul failed to deliver himself from anonymity. All that remains of him are two short film clips, a paragraph-long newspaper item, and my clear memory of how much I loved him—and how much it hurt when I finally found out why he disappeared from my life. But I still remember him a half-century later, and I cried when I saw his face on the screen of my laptop the other day. There are worse monuments.

UPDATE: For the rest of Uncle Paul’s story, go here.

The phrase “guilty pleasure,” of course, is itself inherently problematic, because it implies that we ought to be hypocrites when it comes to our artistic responses. Kingsley Amis said the last word about this deeply wrongheaded attitude: “All amateurs must be philistines part of the time. Must be: a greater sin is to be coerced into showing respect when little or none is felt.” The inverse is also true. I really do like “S.O.S.,” which I believe to be a beautifully crafted pop single, so why should I feel guilty about it?

Generally speaking, though, I don’t fall victim to either error, partly because I don’t give a damn about received opinion and partly because it’s unusual for me to like fundamentally dishonest art. It occurs to me that this might point in the direction of a working definition of bonafide “guilty pleasures” and our responses to them: guilty pleasures let us off too easy by pandering to our innate longing for unearned simplicity. They are the Krispy Kreme donuts of art….

Read the whole thing here.

My brother, like me, is deeply attached to the increasingly distant past that we share. That’s one of the reasons why he and my sister-in-law live in the house where the two of us grew up, and why they have jointly preserved so many homely but cherished souvenirs of our childhood. Among them is a stack of tarnished cans of eight-millimeter film that was shot by my father, a longtime camera bug who first became interested in home movies shortly after I was born in February of 1956. He bought a movie camera that summer, and spent the following decade recording brief snippets of our family life.

The last time I saw my father’s home movies was in 1990, when I screened them as part of my research for a memoir of my small-town days in which they would figure prominently:

The last time I saw my father’s home movies was in 1990, when I screened them as part of my research for a memoir of my small-town days in which they would figure prominently:

For ten years, he carted his gray Bell & Howell camera to family gatherings of every description. At regular intervals, he arranged his three-minute reels of film in chronological order, fitted them out with carefully typed title cards (“Introducing…TERENCE ALAN TEACHOUT”), and spliced them end to end into half-hour programs….

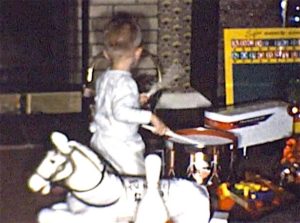

We drag them out and watch them every year or so, laughing and pointing and passing a bowl of my mother’s greasy, salty popcorn from hand to hand. Not all of them are funny. The earliest reels, taken before my father had quite figured out how to work his new camera, are full of oddly haunting glimpses of long-forgotten things: an open field, a country church, a birdhouse, a garden. Even the familiar scenes are lightly touched with mystery, for my father stopped making movies when I was ten years old, and I cannot remember any of the actual occasions on which he shot them. I know that I am the child on the flickering screen because I remember the Christmas toys that surround me: the two-story service station, the red International Harvester tractor, the wheezing toy organ that sits on a table in the basement, still playable, still out of tune. I was there, but I cannot remember a single one of these three-minute snippets of lost time preserved so faithfully by Eastman Kodak that my mother and father and I can watch them in our living room thirty years after the fact.

By then my father was well on the way to his brief, uneasy retirement, and his health was starting to fail. He had never been one for nostalgia, for his own childhood was unhappy and unsettled, and he was no more inclined to reminiscence than he was willing to talk about the world war in which he had served. After he died, my mother showed no interest in looking at his movies, just as she stopped listening to the big-band music that he (and I) loved. Both, I suppose, reminded her too strongly of that which she had lost.

Eight-millimeter home movies have long since become moldy antiques. Indeed, movie film itself is on the far verge of extinction. The generation that followed mine was suckled on home video, while my millennial friends use smartphones to chronicle their lives. You no longer have to buy three-minute reels of film at the drugstore, then ship them off to Kodak to be processed. Today everything is instantaneous and ubiquitous, which to my mind diminishes its preciousness. The easier it is for us to do something, the more we take it for granted—and the less we value it.

Eight-millimeter home movies have long since become moldy antiques. Indeed, movie film itself is on the far verge of extinction. The generation that followed mine was suckled on home video, while my millennial friends use smartphones to chronicle their lives. You no longer have to buy three-minute reels of film at the drugstore, then ship them off to Kodak to be processed. Today everything is instantaneous and ubiquitous, which to my mind diminishes its preciousness. The easier it is for us to do something, the more we take it for granted—and the less we value it.

All of which brings us back to my brother David. A few days ago he sent me a box containing a metal tin of Christmas cookies that he and Lauren, my niece, had baked together in what used to be my mother’s kitchen, using her old recipe. It also contained an unlabeled thumb drive. No sooner did I find it at the very bottom of the box than I inserted it in my laptop, knowing that David has a penchant for sentimental surprises and suspecting at once what this one was.

Sure enough, the drive contained my father’s home movies, converted to three and a half hours’ worth of digital files, faded with age and devoid of sound (yes, home movies were silent when I was a boy) but enthralling all the same. Each scene was as familiar to me as the face I see in the bathroom mirror—yet strange, too, even more so than when I’d last watched my father’s movies a quarter-century ago.

Sure enough, the drive contained my father’s home movies, converted to three and a half hours’ worth of digital files, faded with age and devoid of sound (yes, home movies were silent when I was a boy) but enthralling all the same. Each scene was as familiar to me as the face I see in the bathroom mirror—yet strange, too, even more so than when I’d last watched my father’s movies a quarter-century ago.

The difference is easily explained: my parents are dead now. So is everyone in my father’s family. So are my mother’s parents, and all but one of her siblings. And so, of course, is the simpler, less knowing world of my youth that is enshrined in those faded movies, the self-confident age of Eisenhower and Kennedy, of three TV networks and tuna casserole with crumbled potato chips on top, of films and newspapers and Books of the Month that everyone saw, read, and believed. It lives only in memory, and on the screen of my MacBook.

Memories are especially important at this time of year, to me and, I suspect, to most people who have put youth behind them. “‘I miss.’ That sums up Christmas for me.” So said a thirty-nine-year-old friend of mine the other day, and I knew what she meant. How could I not? I miss my mother and father. I miss my aunts and uncles. I miss the old wooden swing on the porch of my grandmother’s house. I miss the Christmas presents and sliding boards and carefree vacations that my father loved to film. I miss the shadowless summer afternoons (“Summer afternoon—summer afternoon; to me those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language,” Henry James once said to Edith Wharton) when there was nothing to worry about, when my parents did the worrying behind my back and let me assume that all was right with the world.

Memories are especially important at this time of year, to me and, I suspect, to most people who have put youth behind them. “‘I miss.’ That sums up Christmas for me.” So said a thirty-nine-year-old friend of mine the other day, and I knew what she meant. How could I not? I miss my mother and father. I miss my aunts and uncles. I miss the old wooden swing on the porch of my grandmother’s house. I miss the Christmas presents and sliding boards and carefree vacations that my father loved to film. I miss the shadowless summer afternoons (“Summer afternoon—summer afternoon; to me those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language,” Henry James once said to Edith Wharton) when there was nothing to worry about, when my parents did the worrying behind my back and let me assume that all was right with the world.

For a long time I returned each Christmas to Smalltown, U.S.A. I slept in my old bedroom, ate my mother’s cooking, and pretended, even after my father died, that nothing had changed, even though I knew perfectly well that everything had changed. But my mother was growing steadily older and more frail, and by the time of my last Christmas visit, she was tired of life and sick unto death.

That was five Christmases ago. Since then, December has been for me what Dave Frishberg called “the difficult season” in a song that now speaks to me as it has always spoken for those whose childhoods were, unlike mine, dark and troubled: The tinsel, the reindeer, the chimney, the sleigh/Are the innocent dreams of an innocent day/We hark to the carols meek and mild/Awaking the memories of yesterday’s child. Fortunately, my father captured some of those innocent dreams on film, and thanks to David, I can watch them flicker once again to fleeting life.

That was five Christmases ago. Since then, December has been for me what Dave Frishberg called “the difficult season” in a song that now speaks to me as it has always spoken for those whose childhoods were, unlike mine, dark and troubled: The tinsel, the reindeer, the chimney, the sleigh/Are the innocent dreams of an innocent day/We hark to the carols meek and mild/Awaking the memories of yesterday’s child. Fortunately, my father captured some of those innocent dreams on film, and thanks to David, I can watch them flicker once again to fleeting life.

To have had a happy childhood is the greatest of gifts, a permanent source of comfort and inspiration. I need no home movies to drink from that self-renewing source, but I’m still lucky to have them—and to have a brother to whom they mean as much as they do to me.

A scene from the 1940 film version of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, adapted by Wilder, Frank Craven, and Harry Chandlee from Wilder’s play and directed for the screen by Sam Wood. The score is by Aaron Copland. Craven and Arthur Allen, who play the stage manager and Professor Willard, created their roles in the original 1938 Broadway production:

A scene from the 1940 film version of Thornton Wilder’s Our Town, adapted by Wilder, Frank Craven, and Harry Chandlee from Wilder’s play and directed for the screen by Sam Wood. The score is by Aaron Copland. Craven and Arthur Allen, who play the stage manager and Professor Willard, created their roles in the original 1938 Broadway production:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

“I like filmed theatre; I think there is a charge and a glamour about filmed plays and revues and vaudeville and music hall that one rarely gets from adaptations of novels or from those few screen ‘originals.’ Filmed plays are often denigrated, somewhat dishonestly, by people who learn a little cant about what is said to be proper to the film medium and forget about the pleasure they’ve been getting from filmed plays all their lives.”

“I like filmed theatre; I think there is a charge and a glamour about filmed plays and revues and vaudeville and music hall that one rarely gets from adaptations of novels or from those few screen ‘originals.’ Filmed plays are often denigrated, somewhat dishonestly, by people who learn a little cant about what is said to be proper to the film medium and forget about the pleasure they’ve been getting from filmed plays all their lives.”

Pauline Kael, “Filmed Theatre” (The New Yorker, Jan. 11, 1969, courtesy of Jason Zinoman)

A scene from “The Night of the Meek,” an episode of The Twilight Zone originally telecast by CBS on December 23, 1960. The cast includes Art Carney and John Fiedler and the teleplay is by Rod Serling:

A scene from “The Night of the Meek,” an episode of The Twilight Zone originally telecast by CBS on December 23, 1960. The cast includes Art Carney and John Fiedler and the teleplay is by Rod Serling:

(This is the latest in a series of arts-related videos that appear in this space each Monday, Wednesday, and Friday)

An ArtsJournal Blog