If my family had any dark secrets, they went to the grave with my parents, grandparents, aunts, and uncles. But like all families, we did have a few subjects of which we preferred not to speak save in hushed tones, foremost among them the fate of my Uncle Paul.

Paul ran a service station and, later on, sold used cars. He was a beloved and trusted figure of my boyhood, so much so that I would spend the night with him and Aunt Suzy, my mother’s sister, on the rare occasions when my parents went out of town together. I remember him as a warm, affectionate man who taught me how to sing “You Are My Sunshine” and “How Dry I Am” (a grimly ironic choice of tunes, given what happened to him) and play shuffleboard (he’d painted a court on the floor of his basement). But Paul disappeared from my life in the mid-Sixties, and the only thing my parents told me at the time was that he and Suzy had gotten a divorce, an occurrence that was all but unthinkable among my mother’s people, who were the most devout of small-town churchgoers.

Paul ran a service station and, later on, sold used cars. He was a beloved and trusted figure of my boyhood, so much so that I would spend the night with him and Aunt Suzy, my mother’s sister, on the rare occasions when my parents went out of town together. I remember him as a warm, affectionate man who taught me how to sing “You Are My Sunshine” and “How Dry I Am” (a grimly ironic choice of tunes, given what happened to him) and play shuffleboard (he’d painted a court on the floor of his basement). But Paul disappeared from my life in the mid-Sixties, and the only thing my parents told me at the time was that he and Suzy had gotten a divorce, an occurrence that was all but unthinkable among my mother’s people, who were the most devout of small-town churchgoers.

Paul came to our house a couple of years later for a very brief nighttime visit about which I recall nothing but the fact that it took place. If memory serves, my brother and I had already been put to bed when he unexpectedly showed up on the doorstep, and our parents didn’t get us up to see him. A few weeks after that, he was run over by a truck and killed.

My mother then told me that Paul had been an alcoholic, and that he’d stayed away from my brother and me because he didn’t want us to see what had become of him. It was the first time I’d heard the word “alcoholic,” and she had to explain to me what it meant. Suzy, she said, had left him because of his drinking, then came back when he started going to AA meetings. But he couldn’t stay sober, and when she left him again, it was for keeps. My mother said that he’d gotten drunk and wandered into the path of an oncoming truck, and she left me with the impression that she thought he’d done it deliberately.

Paul was the first person to die to whom I was close, and his death left a deep mark on my psyche. I suspect it’s the main reason why I’ve never been much of a drinker. But while my mother always spoke of him with fondness, the other members of the family never mentioned Paul again except when prompted. Some of them, I’m sure, were ashamed of him, for in those days it was widely taken for granted that alcoholism was not a disease but a moral weakness, and those who succumbed to it were viewed with contempt.

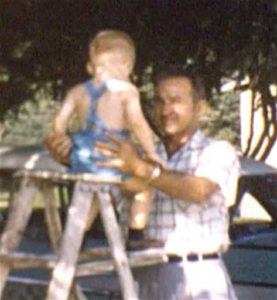

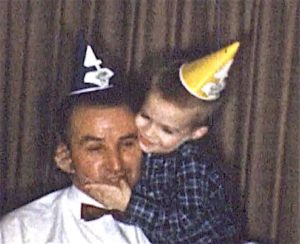

So far as I can recall, I’ve never seen a still picture of Paul, but he does appear in two of the home movies that my father shot between 1956 and 1966 and that my brother sent to me last week as a Christmas present. In the first scene, he is standing behind a ladder in the driveway of my grandmother’s home, watching as I climb to the top rung, then taking me in his arms. In the second, he is sitting beside me at my fourth birthday party. The love that we felt for one another is plain to see in both clips.

So far as I can recall, I’ve never seen a still picture of Paul, but he does appear in two of the home movies that my father shot between 1956 and 1966 and that my brother sent to me last week as a Christmas present. In the first scene, he is standing behind a ladder in the driveway of my grandmother’s home, watching as I climb to the top rung, then taking me in his arms. In the second, he is sitting beside me at my fourth birthday party. The love that we felt for one another is plain to see in both clips.

Seeing Paul after so many years made me wonder whether I might be able to find out anything more about him on the Web. I Googled his name, and this short newspaper piece, originally published in the Cape Girardeau Southeast Missourian in 1958, popped up:

Paul Armsby, owner of Paul’s 66 Service Station at 340 S. Sprigg St., has received a $50 award from the Phillips Petroleum Co., for giving perfect driveway service to a Phillips “mystery motorist.” In the picture he is shown at the left receiving the award from D.V. Shaner, district salesman. Others in the picture at the left are station attendants, Don Hency and Richard Gerlach.

Beyond that…nothing. Paul and Suzy had no children, and I don’t know whether any members of his own family are alive. He seems to have been born in Arkansas in 1919 or 1920, but I can find no record of his death, nor was an obituary published in any of the local newspapers. Save for that lone paragraph in the Southeast Missourian, it’s as though he’d never existed. I don’t even know where he’s buried. I greatly regret to say that I made no mention of him in the memoir of my childhood that I published in 1991, mainly because I wanted to spare Suzy’s feelings (she had not yet died when the book came out).

Beyond that…nothing. Paul and Suzy had no children, and I don’t know whether any members of his own family are alive. He seems to have been born in Arkansas in 1919 or 1920, but I can find no record of his death, nor was an obituary published in any of the local newspapers. Save for that lone paragraph in the Southeast Missourian, it’s as though he’d never existed. I don’t even know where he’s buried. I greatly regret to say that I made no mention of him in the memoir of my childhood that I published in 1991, mainly because I wanted to spare Suzy’s feelings (she had not yet died when the book came out).

I find it unutterably sad that my Uncle Paul has vanished almost without trace. It puts me in mind of something that H.L. Mencken wrote in 1927:

I have done a great deal less than I wanted to do and a great deal less than I might have done if my equipment had been better, but this, at least, I have accomplished, and it is one of the principal desires of man: I have delivered myself from anonymity.

Like most of the rest of us, Paul failed to deliver himself from anonymity. All that remains of him are two short film clips, a paragraph-long newspaper item, and my clear memory of how much I loved him—and how much it hurt when I finally found out why he disappeared from my life. But I still remember him a half-century later, and I cried when I saw his face on the screen of my laptop the other day. There are worse monuments.

UPDATE: For the rest of Uncle Paul’s story, go here.