I have a theory that you don’t become a full-fledged adult until you’ve weathered the death of someone with whom you are intimate, not in distant memory but at the actual moment of that person’s demise. (You get a pass if you yourself come close to dying, but not otherwise.) If that’s so, then I grew up at the end of 1995, two months shy of my fortieth birthday, when my best friend died a painful, senseless death to whose details I was fully and agonizingly privy. I saw her the night she learned she had cancer, stood by her hospital bed mere hours before she died, and helped clean out her apartment a few days later, in the process throwing away the wig that replaced her hair after she underwent chemotherapy.

By then all of my grandparents had died, the last one in 1989. I wasn’t close to any of them, though, and I’d somehow managed not to lose any good friends to AIDS, no small trick in those days for a Manhattanite who was, like me, immersed in the arts. My parents were both still alive and reasonably well. What’s more, I’d never actually seen anyone die, and even though I took it for granted that death on the silver screen was an exercise in glossy euphemism, you couldn’t have proved it by me.

By then all of my grandparents had died, the last one in 1989. I wasn’t close to any of them, though, and I’d somehow managed not to lose any good friends to AIDS, no small trick in those days for a Manhattanite who was, like me, immersed in the arts. My parents were both still alive and reasonably well. What’s more, I’d never actually seen anyone die, and even though I took it for granted that death on the silver screen was an exercise in glossy euphemism, you couldn’t have proved it by me.

One result of this fortuitous distancing from death was that I had yet to take in the fact that it is, as Philip Larkin (who desperately feared his own dying) put it, “sure extinction,” something that happens to everyone, meaning that it would someday happen to me. To know a fact is not necessarily to feel it. It wasn’t until my friend died that I finally started to feel it. From that moment on, I knew in my bones that I, too, would someday follow her into the grave.

I doubt it’s any kind of coincidence that my life, which had hitherto been little short of charmed, grew alarmingly bumpy shortly thereafter. I lost another friend to cancer a year and a half later, and my father died of it nine months after that. In the fall of 2001, right around the time of 9/11, I started grappling with a series of disruptions in my personal life that between them added up to what can fairly be called a midlife crisis. By the end of 2005, my hair was gray. That was when I became seriously ill for the first time in my life, ten years to the week after my friend’s death. So ended my forties, and I was more than happy to be done with them.

I should note that I kept myself exceedingly busy throughout that dread decade. I became a drama critic, published three well-received books, and began to collect art in an increasingly serious way. Even more important, I made a phalanx of friends whose abiding love kept me afloat when I wondered whether I might be headed for the rocks. Nevertheless, it was a hell of a time, inside and out, and I feel certain in retrospect that the death of my friend was what set it in motion. After that, I could no longer suppose myself invulnerable.

Yet it was at this very moment that my life righted itself and started to move down a different path. I had met the woman who became Mrs. T a few weeks before I went into the hospital, and we’ve been together ever since. I was already at work on Pops, and Paul Moravec and I started writing The Letter that spring. If you follow this blog more than casually, you know the rest of the story. Much to my surprise, I spent my fifties making art on the side, and I hope to spend my sixties making even more of it.

Yet it was at this very moment that my life righted itself and started to move down a different path. I had met the woman who became Mrs. T a few weeks before I went into the hospital, and we’ve been together ever since. I was already at work on Pops, and Paul Moravec and I started writing The Letter that spring. If you follow this blog more than casually, you know the rest of the story. Much to my surprise, I spent my fifties making art on the side, and I hope to spend my sixties making even more of it.

I believe that it was Mrs. T who made this transformation possible. But I also believe it wouldn’t have happened had it not been for my belated discovery of what Henry James called “the distinguished thing.” Not only did my newfound consciousness of the inevitability of death set off an interior turmoil that rid me forever after of any semblance of complacency, but it forced me to remember the words of Cardinal Newman to which I alluded in this space when I turned sixty earlier this year: And, ere afresh the ruin on me fall,/Use well the interval. Even when I was at my unhappiest, I worked—hard—and I worked just as hard at being the best friend I was capable of being. I had learned not to waste time. That’s why I was ready to take full advantage of my new situation when the wind finally changed.

I was talking to a friend of mine the other night about all this. At fifty-five, she is going through a similar personal transformation, and we agreed that the key to “using well the interval” is, quite simply, not to be afraid of looking silly in the eyes of other people. Early in the life of this blog, I posted a remark that Robert Penn Warren put in the mouth of Willie Stark, the anti-hero of All the King’s Men: “But listen here, there ain’t anything worth doing a man can do and keep his dignity. Can you figure out a single thing you really please-God like to do you can do and keep your dignity? The human frame just ain’t built that way.”

I was talking to a friend of mine the other night about all this. At fifty-five, she is going through a similar personal transformation, and we agreed that the key to “using well the interval” is, quite simply, not to be afraid of looking silly in the eyes of other people. Early in the life of this blog, I posted a remark that Robert Penn Warren put in the mouth of Willie Stark, the anti-hero of All the King’s Men: “But listen here, there ain’t anything worth doing a man can do and keep his dignity. Can you figure out a single thing you really please-God like to do you can do and keep your dignity? The human frame just ain’t built that way.”

Anthony Powell put it differently but no less pithily in the first volume of A Dance to the Music of Time:

Later in life, I learnt that many things one may require have to be weighed against one’s dignity, which can be an insuperable barrier against advancement in almost any direction.

The point, I think, is that you must not be afraid to fall on your face if you want to get anywhere in life, and most especially if you want to try doing something new late in life. And if you are aware—intensely, consumingly aware—that the clock is running and time may be short, you’re less likely to be stymied by the fear of falling on your face in front of an audience.

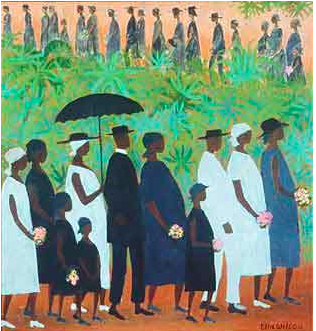

Not long after I started working on Satchmo at the Waldorf, I had a new business card printed up that bears on its reverse side the image reproduced here. I did it in order to remind myself of how important it was not to be afraid to fail, whether in private or in public. If you aren’t willing to take chances—to quit your unsatisfying job without having a new one lined up, to say “I love you” without having it said to you first, to try your hand at writing your first play at an age when most professional playwrights have already written twenty—then you’ll probably spend the rest of your life doing exactly what you’re doing right now, regardless of whether or not you’re happy doing it. And if the clock with no face should stop ticking unexpectedly, then your last thought will very likely be Oh, God, it’s too late now!

Not long after I started working on Satchmo at the Waldorf, I had a new business card printed up that bears on its reverse side the image reproduced here. I did it in order to remind myself of how important it was not to be afraid to fail, whether in private or in public. If you aren’t willing to take chances—to quit your unsatisfying job without having a new one lined up, to say “I love you” without having it said to you first, to try your hand at writing your first play at an age when most professional playwrights have already written twenty—then you’ll probably spend the rest of your life doing exactly what you’re doing right now, regardless of whether or not you’re happy doing it. And if the clock with no face should stop ticking unexpectedly, then your last thought will very likely be Oh, God, it’s too late now!

As for my late friend, I met her a year and a half before she died. It was only because I reached out to her instantaneously and unhesitatingly on our first meeting that we were able to share each another’s company for that precious year and a half. We didn’t have much time together, but we didn’t waste what little we had. I have no illusions of any kind about death—having seen it up close, I know how terrible it is—but I also believe that it was what taught me to take chances with life instead of hoarding it. I will never, ever be grateful that my friend died, but I will always be grateful that I learned so priceless a lesson from her death. May you learn the same lesson, sooner than I did.

* * *

Christine Ebersole sings Stephen Sondheim’s “Not a Day Goes By,” from Merrily We Roll Along: